Profligate Spending, Poor Returns

Does this government want to see a large number of bankruptcies piling up under its watch?

Indian government deficits, both fiscal and current account, are reported to be in decline via accepted norms of accounting compartmentalisation. They are simultaneously and otherwise estimated to be at multiples of what the official reports would suggest.

The Indian juggernaut is remarkably profligate in its spending. This is obvious to the casual observer, who has to remind himself, that this is an ‘emerging economy’ and not some hugely rich kingdom with separate kings at every lamppost.

The government spending we see is mostly and audaciously self-serving in terms of where and how it is applied. The ruling sarkari classes: bureaucracy and politicians alike are united in this. So, there is little left over in any budget or ad hoc pool for growth and development aimed at the people, either on revenue earned or borrowed basis. But new taxes and cesses are ever popular, in place of any kind of government belt-tightening or efficient use of capital.

Most of what the government borrows goes, in fact, to pay off other borrowing already in place! Where does the voter figure in all this? Certainly not very high on any real list of priorities, though the people, particularly the poor, are often invoked as an alibi.

Still, the sharp oil price decline, now at below $37 a barrel down from over $110, has helped dramatically to better the comparative figures on deficits, and inflation too.

In an Orwellian sense, the deficits have indeed declined during the nearly two years of the Modi government, but only against itself, as selectively defined. But, to what, beyond the declining price of oil, and thereby the smaller petroleum import bill, can we attribute the betterment to?

What we call the total fiscal and current account deficits, doesn’t count up a lot of outstanding borrowed expenditure; much of it knowing future bad debt, that is sitting under various other heads, both at the centre and the states, and in the books of state owned utilities and the like. These together, are said to be nothing under 10 -15per cent of GDP, at a conservative estimate.

But reports that come up with this ‘actual deficits are much higher than realised’ thesis, laden with statistics, graphs, charts, and difficult economic theory, as they tend to be, are not appreciated by any government of the day. They don’t want to think about it, because much deficit spending is either for its own benefit, or vote seeking and populist in nature – free electricity, free other things, known unprofitable ventures; and they don’t want the exposure. Just imagine so many overweight emperors with no face saving clothes.

Besides, reports on national deficit financing etc. tend not to be understood outside of accounting, rating/analyst and economist circles, and therefore are largely given the miss by the mass media as well.

The readerships statistics on editorials and op-eds may be rising as a tool to self-improvement, but as a percentage of total readers of media output, they tend to be in the single digits, here and indeed worldwide.

But when it comes to deficits, the most powerful country in the world, the United States, counts its national debt in ever ballooning but unfazed trillions, supported by little beyond its credibility by way of collateral.

Its allies across the pond, including Germany and France, are not exactly debt-lite either. In fact the entire borrow-and-spend West is in recession, with several of the smaller components of the EU quite bankrupt today, because of this great way to get ahead, in vogue ever since the eighties.

Governor Raghuram Rajan of the RBI, first became world famous while working at the IMF, for predicting, most unpopularly, that the party was going to end in tears, some years before 2008 happened.

Meanwhile, India is said to be growing at 7.5 per cent in terms of GDP after the method of calculation was changed. According to the old method, again not amplified on much by anybody, we are still languishing at some 5.2 per cent. And the real rate of growth after inflation depends on the sleight of hand you best fancy.

In any event, though 7.5 per cent is meant to make India the fastest growing major economy in the world today, better than China, growing at slightly less, with its $ 12 billion economy. But the real point is that China is over-built and played out in terms of its export model, and India may be just getting started, at its traditionally elephantine pace.

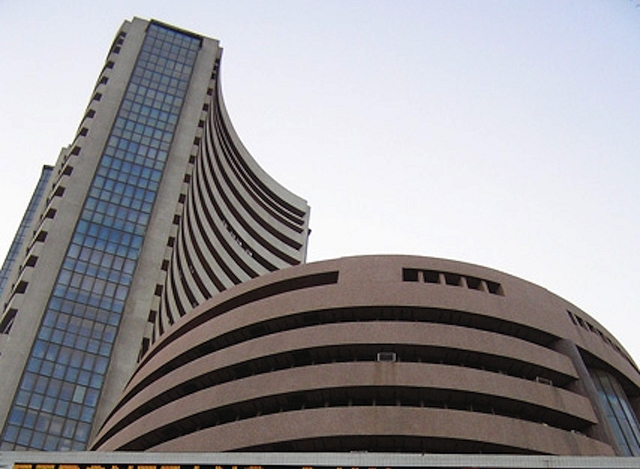

India is, in any case, operating from a low base of approximately two trillion dollars. But many serious commentators have said that it certainly does not feel as if the economy is growing at over seven per cent. Industry and services, agriculture and incomes, all seem to be stagnating instead. Life is tough. Making ends meet is not getting easier. Where are the new jobs? One quarter of the youngsters under 25 are said to be looking for jobs. The stock and property markets are going nowhere.

The official growth rates must be correct, if the statistics say so, and international rating agencies such as Moody’s and Fitch accept it. But it is a wonder why they do accept it. Probably because they conform to the same international principles that has the world in a lot of economic trouble presently.

But the suspicion in the common mind is that maybe the statistics are convoluted, and are missing the real state of play. Will all of this, domestically and internationally blow up into another major crash, worse than the first, despite the pump priming of billions over years or maybe because of it? Many economists say yes. The world as such however, is in denial.

In India, most state revenues are far short of expenditure, as are the expenses versus income of the central government. Besides there are historical debts racked up in previous years, sometimes by previous governments, still largely outstanding. These eat away at current state allocations from the centre, as well as whatever revenues it generates within the state. Interest piles up on unpaid interest, compounding its way towards a ruinous, unaffordable, write- off eventually, time and again.

Economic packages are demanded and granted, and all the while the deficit funding keeps ballooning. OROP and the seventh Pay Commission under process, is going to cost the government a pretty penny, and though the stimulus to the economy in many consuming hands is welcome, even the official deficit targets have had to be pushed back to future years.

Productivity and return on capital, the drivers of healthy economic activity, are however, largely missing in action, even in the private sector, and certainly in the government, and the public sectors it runs.

It is no wonder that Raghuram Rajan, a fiscal conservative, has been harping on the bad debt situation of the PSU banks. It is not his job, but if he was the finance minister and wasn’t a politician in that role, he’d have a great deal more to say about the parlous state of the government’s finances and its massive public debt spiralling ever higher as well.

Rajan wants the bankruptcy law as soon as possible to clean up the books. But the government, after considering passing it as a money bill in the Winter Session’s last days, has pushed it down the pike to a joint parliamentary committee to consider. It won’t surface before the budget session in February 2016 at a minimum now.

But the moot question is, does this government want to see a large number of bankruptcies piling up under its watch? Cleaning up the burden of debt in the banks may be important to the professionally manned RBI, but can be very embarrassing and politically damaging to the Modi government.

Which Pandora’s Box should be opened voluntarily? Shouldn’t they all stay firmly closed?