Slowing Consumption: Cues That The Monetary Bosses Must Sit Up And Take Note

The reasons for sluggish consumption growth are many but an important factor is the increase in real cost capital at a time of low inflation.

Fiscal measures will help in the revival, but their effectiveness will depend on the corrective actions monetary bosses take.

The recent slowdown in consumption has started a debate regarding various policy options that are available with the government to address the problem. Leading economists, seasoned commentators and public policy experts have come out with their prognosis of the current situation along with their respective policy prescriptions.

This is an attempt to add to the current discussion on the recent consumption slowdown. Dr Rathin Roy has made a strong case regarding saturation of the consumption growth amongst the affluent sections of the population.

It is only normal that beyond a point there is limited scope for consumption to grow, however India has consistently increased its share of middle class. Be it the upper middle class or the lower middle class, India has a decent number of people in both segments and therefore, this hypothesis can at best only explain a part of the slowdown in consumption.

There are two major developments that have happened over the last couple of years that have to be kept in mind when one looks at consumption.

First is that there has been a fall in household savings, and this has coincided with an increase in the amount of debt held by households.

The second is that inflation has remained modest over the last five years — in fact, it has been muted across the world (refer to ‘Is inflation dead?’ by clicking here).

The fact that we have witnessed low levels of inflation has a lot of implications for the economy.

For starters, during low inflation levels, the nominal increase in income is relatively lower compared to times when inflation is relatively higher. This is to ensure that the real increment is the same.

The increase in the amount of debt points at the fact that perhaps of lately, consumption growth was fuelled by debt rather than actual increase in income.

We know that private consumption has increased by 53 per cent between 2013 and 2017 but personal loans have witnessed an increase of 89 per cent. A major share of this increase in loans is concentrated in areas such as consumer durables, vehicles, housing or other personal loans.

In fact, other personal loans grew at 154 per cent. This suggests that indeed, low inflation and low nominal growth rate have resulted in households looking to finance consumption through borrowings.

Now here’s where we have a problem — when inflation reduces, nominal increments respond on an annual basis. But EMIs don’t — thanks to our monetary masters and transmission problems.

Consequently, as inflation decreases, the share of household income going towards repayment of existing debt increases as policy rates don’t adjust as much as they should. This has continued for the last couple of years and no wonder we witness a slowdown in consumption.

The situation gets far worse when one considers existing borrowings to finance real estate assets. The massive accumulation of inventories in the sector has resulted in prices dropping in major cities across the country.

Therefore, the value of physical asset has reduced while the real cost of financing the asset has gone up. If this is not a recipe for disaster, then what is?

There are indeed sector specific concerns that need to be adequately addressed and many commentators have argued for government to increase its spending in order to revive consumption growth.

While government spending will help but we need to simultaneously address the monetary side of the problem. Cost of financing a house for instance should come down to ensure some movement of the current accumulated inventories.

At present, India’s real interest rates are at 2.2 per cent down from 3.43 per cent in April 2019 (they were at 4 per cent in March).

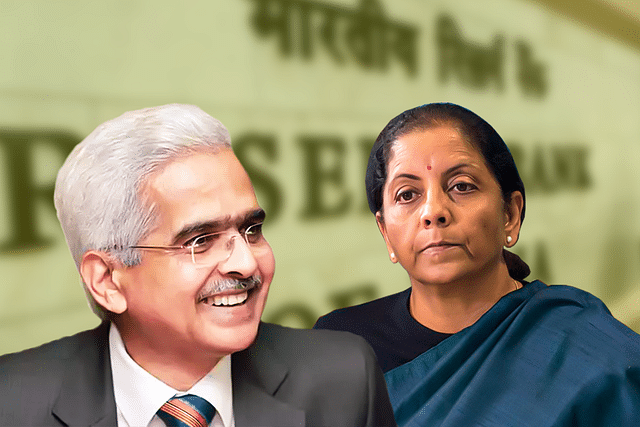

The average real repo rate was at 2.8 per cent during the first half of this fiscal year and therefore, there’s a definite need for the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of Reserve Bank of India to be much more aggressive in terms of cutting the policy rates.

It is their slow approach towards reducing policy rates combined with the transmission woes that have only worsened the current slowdown.

While the MPC gets its act together, there’s an urgent need for the Finance Ministry to immediately cut small savings rate and deposit rates across tenures. This may have an impact on savings, but one must understand that inflation is dead and therefore, by keeping nominal interest rates high is only hurting the economy.

The best way is to link these rates with repo rates to allow for seamless transmission of monetary policy. Only when marginal cost of lending rate (MCLR) of major banks reduces substantially, and the burden of EMIs reduces will both our households and corporate sector be left with adequate surplus to either consume or save (or invest).

The best way to ensure smooth monetary transmission would be to link both lending and deposit rates with repo rates.

The current problem of sluggish consumption growth is due to many reasons, some structural, some cyclical. But an important contributory factor is that at a time when inflation is low, we have increased our real cost of capital.

No wonder, consumption growth has slowed down and while fiscal measures will help in revival, but the effectiveness of such measures will depend on whether our monetary bosses realise their mistakes and take corrective action.