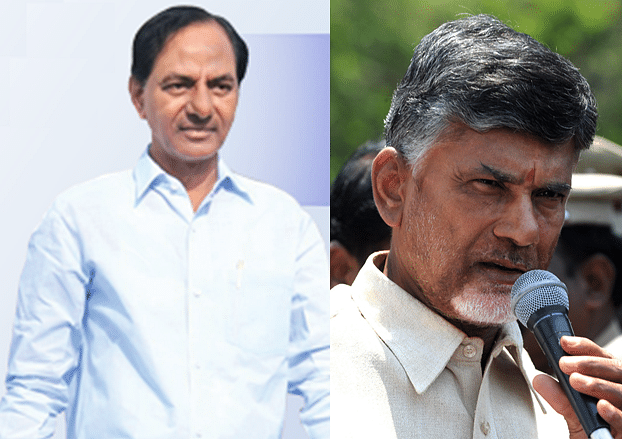

Telugu Twins, BJP States Top Ease Of Business Ranking; Didi & Kejriwal Slip

Between last year and now, almost all Indian states have improved their scores under the Business Reform Action Plan of the DIPP.

The race to the top has resulted in a tie between the recently divided states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, and Gujarat is ranked third.

While the rankings indicate a largely positive trend, there are some worrying aspects, including to do with the nature of local benchmarking of this kind.

Competitive federalism seems to be working. Many Indian states have gotten serious in trying to improve their rankings in terms of ease of doing business.

Between last year and now, almost all Indian states have improved their scores by substantial amounts – by 10-30 points – but the race to the top has resulted in a tie between the recently divided states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Dethroned in the process from No 1 is Gujarat, but only by a whisker. While Andhra and Telangana scored 98.78, Gujarat got 98.21, relegating it to No 3.

The scale of improvement in each case can be gauged from the fact that last year, the top three had scores in the early 70s. This time they are approaching 100 – the perfect score. This is what is troubling about the rankings. If states can be near-perfect, their scores looking like marks obtained in tenth-class board exams in various states, one wonders if the system can be gamed by those seeking to gain a propaganda advantage.

But we can perhaps learn more from those who didn’t do well. Among those who slipped this time are Didi’s West Bengal, Amma’s Tamil Nadu and Arvind Kejriwal’s Delhi. While Didi and Amma made huge improvements in their own scores compared to last time (West Bengal by a phenomenal 37 points and Tamil Nadu by 18), Delhi rose by a mere 10, and figures in the second half of the rankings. This means Didi and Amma did very well, but others did better. The inexplicable decline is Delhi, which is well-placed both in terms of infrastructure and entrepreneurial talent to score much, much higher. Kejriwal has work on his hands, once he stops gallivanting around Punjab and Goa.

The ranking, officially called the Business Reform Action Plan of the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP), is based on state-level implementation of a 340-point plan cutting across 10 major areas: construction permit enablers, labour regulation enablers, environmental registration enablers, (ease of obtaining) electricity connections, online tax filing, inspection reform enablers, access to information and transparency enablers, single window facilities, commercial disputes resolution enablers and land availability.

If last year the reforms involved 98 specific aspects of ease of doing business, this time the number of reform measures monitored went up to 340. The ranking is real-time and online, and so states can see where they lag and improve themselves. They can also learn from best practices.

Broadly speaking, Bharatiya Janata Party-ruled states seem to be doing rather well, taking up seven of the top 10 rankings. Last year there were six. Uttarakhand is the only Congress-ruled state in the top 10 (at No 9), but Karnataka, the biggest Congress-ruled state, is down to No 13 from No 9 the last time.

The top 10 are: Andhra & Telangana, Gujarat, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, and Maharashtra.

Dropping off by several places from last time are West Bengal (No 11 to 15 this year), Tamil Nadu (12 to 18) and Delhi (15 to 19). (See last year’s ranking here)

While Tamil Nadu, gripped by concerns over Amma’s health, may have dropped due to the top-level uncertainty, Delhi’s drop under Kejriwal seems surprising, since he is supposed to be focused on reducing corruption and improving administrative efficiencies. Maybe if he were battling a little less with Prime Minister Narendra Modi and focusing more on governing, his state’s rankings would have been better. West Bengal’s drop is also surprising, for Didi has been trying to woo businesses to the state and is set to hold her third global business summit in 2017.

The pluses and minuses of this ranking are the following:

Plus: Since the defined areas of reform are crystal clear, states can be proactive in reducing areas of weakness, and learn from the best practices of other states.

Minus: While a state may score high on one parameter, actual ease of doing business depends on how decisions are implemented and how investors see these improvements.

Plus: Improving a score is good in itself, for it means a state is trying to make life easier for business.

Minus: Scoring better than the last time will not help a state if other states have done even better. Thus, while all states have improved their scores, many have slipped ranks, not least Gujarat, which under Modi never ceded the No 1 rank. Despite a phenomenal improvement in score from 46.9 last year to 84.2 this year, West Bengal slipped.

Plus: Most states seem to be improving their scores, which means the rankings are making states conscious about making ease of doing business a priority. Last year only seven states had scores over 50; this time 17 states crossed the half-way hump. That’s progress.

Minus: The laggards are still too many, especially the smaller states and Union Territories, which seem to be losing visibility. The bottom 12 states and Union Territories, mostly in the north-east and micro zones like Lakshadweep, were not able to score even one or two points. They are clearly the boondocks of investment.

Kerala, which prides itself on being the country’s most literate state with high human development indicators, does not seem to care about the ease of doing business, with a score of 26.97 (No 20).

God’s own country, now run by presumably godless Communists, does not seem to be a good place to do business in.

The real worry is this: how much scope for improvement will the top three states think they have when they are just one or two marks below 100? Something not quite right here. Despite the fact that these states may be good to do business in, surely they are not Singapore or New Zealand when it comes to ease of doing business?

At some point, we need global benchmarks, and an external ranking of states by actual investors.