Unputdownable Short Term Stimulus: Cut Corporate Tax Rates Big Time, Cut Interest Rates Big Time

In the short term, two things are needed: for the government to reduce corporate tax rates, and for the RBI to slash interest rates.

The crash in the growth rate of GDP to 5 per cent, the lowest in 25 quarters piled on the scare of a recession in key economies of the world, making it essential for the central government to take two urgent but sensible steps.

It has to make the cost of money far cheaper than any comparable economy can offer and make more of that money available, both very fast. This means it has to offer massive corporate tax cuts (not income tax cuts since those will stimulate consumption but give no investment push) and nudge the Reserve Bank of India to cut rates far deeper than what it has offered so far.

It is also easy to list out things both RBI and the centre should not do like the earlier government did in the face of a downturn in 2008.

They should not cut rates in homeopathic doses and offer fiscal stimulus to all and sundry sectors. That will only worsen the bank balance sheets, once again.

Seeing the centre take these quantum sensible steps will also wash away the bad memories created by watching the Chief Economic Advisor, on Friday evening, try to offer a trite comparison of the present slowdown with the ones under the UPA government.

The justification for offering this unusual combination, quite an anathema to the Indian bureaucracy, which expects to offer reliefs only in small doses for fear of offending the 3Cs—CAG, CVC, and CBI, is that reform measures for ratcheting up the economy in the medium term like the announcement of the mergers of four sets of public sector banks are not a substitute for action to revive the economy in the short term.

The set of announcements made last week, like rolling back the surcharge on tax on FPIs were excellent. But those do not encourage investment and would only boost the price discovery for the same limited set of equities in the stock market.

New companies and even the old ones are not about to float attractive public issues this year, the declared pipeline for new issues is thin (there has been only 12 so far this calendar year against 21 in the same time frame of 2018).

There were six issuances by the public sector last year, compared with only one this year. This means unless the centre institutes some drastic steps there is a risk that even the disinvestment targets set in the budget might not be met. Without the projected Rs 108,000 crore to be realised from disinvestment, this could blow a hole in the fiscal math. It would potentially worsen the dip in the economy.

It would be better to miss the target deliberately to give a clear direction to the economy than arrive short without a plan, which is a distinct possibility now.

For a cash-strapped government, the suggestion to cut tax rates at this scale for companies may seem like madness but remember these are exceptional times.

Carried out soon by a mid-term budget like announcement, these would energise the economy as cash with the companies will encourage them to plough it back for investment--paying it out as dividend will attract more tax.

The government has done enough on the welfare front for the lower end of the income table with a litany of largesse that pretty much satisfies the definition of a dole. There is little option left for the centre to offer any additional tax sops for rural India since it does not raise much direct tax from it and the roll out of various income support is continuing apace.

Having kept the doles ring fenced from the bite of a slowdown, the centre is also in a politically strong position to do a deal with the companies without being held up for favouring them disproportionately.

The step will be quite akin to a gamble but it would be interesting to know if any one has a better option to offer. I suspect no one has. For instance, is there merit in pushing for deep labour reforms as an alternative, at this stage?

I do not suggest that labour reforms are of peripheral importance, but India will need to do a lot of legwork like intense collaboration with the state governments comparable to the run up to GST, to gain traction from this reform.

For these reasons it can hardly be written up as a short term menu. India will surely have to build up labour arbitrage as a medium term goal which will come in useful when the next downturn strikes. But not having prepared ourselves to take advantage of building up the supply of cheap and skilled labour, it cannot be our weapon of choice at this juncture. But it should also not mean we should offer sectoral tax sops. It would also not work.

So once the companies get a tax break at this scale and are told that tax exemptions will be eliminated post haste, they will find virtue in using the money to ramp up capacity. This will open up a virtuous cycle of investment to kick start the economy.

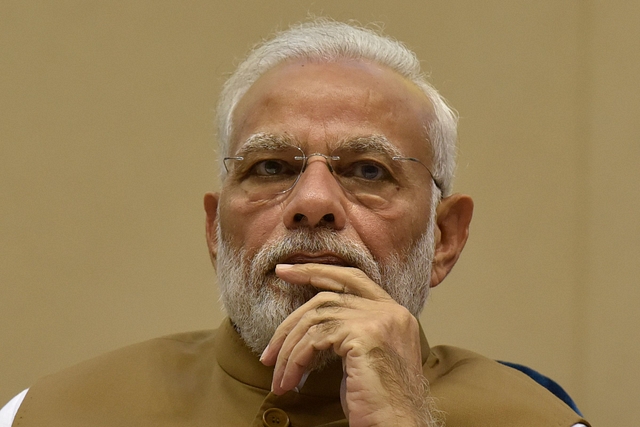

Modi has to deploy his political capital to take the lead since he has more than four years of his term left to ensure the tax sops reach the right companies. Allied with the deep interest rate cuts this will most certainly set the Indian economy on the road to a rapid recovery.

A crisis would have been used well.