Jerry Rao: A Tactical Alliance With Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand was mediocre novelist, but given her enduring popularity in India, she can be used as the Trojan horse to direct India’s young away from the sterile paths of socialism, collectivism, statism and state paternalism

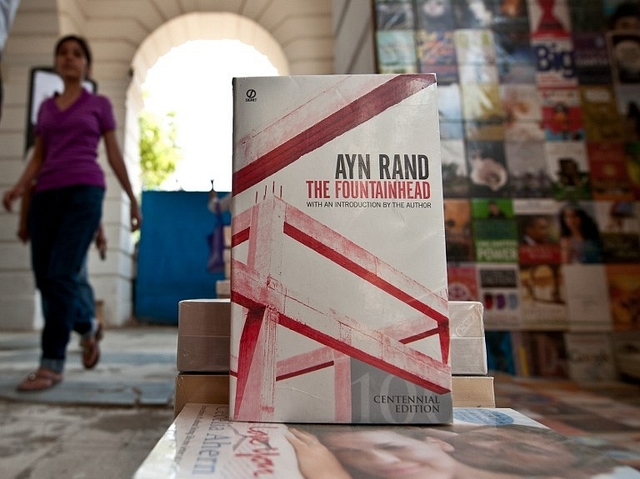

One of the interesting news snippets that I ran across is that India has one of largest groups of young people in the world, who are interested in Ayn Rand. This should constitute a great source of hope and excitement for all of us who are engaged in trying to spread the message of the overarching importance of individual freedoms. I have always felt that Ayn Rand is a pretty mediocre novelist.

Her characters are wooden and stereotypes, rather than flesh-and-blood complex individuals. Her situations tend to be simplistic binary ones. But of course, it is not the quality of her fiction that makes her such a compelling read. It is the fact that her fiction is merely a medium for conveying with extraordinary emphasis, her basic philosophy that progress is possible for humankind and that the only way to achieve this progress, that everybody desires, is by unleashing the energies of the dedicated individual.

Collectivism will doom us to a world of envy, a world of mediocrity and a world where while being seduced by fantasies of utopias, individuals will cease to be free sovereign human beings and become servile cogs in a gigantic statist wheel.

Keeping Ayn Rand on Indian best-seller lists, disseminating her ideas, hosting seminars where Ayn Rand is the focal point of discussions, encouraging study groups to talk about Rand–all of these are ways that we should consider to expand the attractive beachhead which we already seem to have acquired among the young in India.

Ayn Rand, can in effect, become the proverbial Trojan horse which we can leverage in order to direct India’s young away from the sterile paths of socialism, collectivism, statism and state paternalism, all of which are so prevalent in our academic, political, bureaucratic and journalistic spheres.

Ayn Rand has an appeal to the hard-headed as well as to those who are attracted to starry-eyed aspirational ideals. It is this combination of being grounded in consequential empiricism, while appealing to the indomitable spirits within each of us that we need to keep pushing as our near-biblical message.

The emergence of entrepreneurial energy in unlikely places, or places which people considered unlikely, without any rationale, is one more theme we can and we should focus on. In this context, one book that I would like to recommend to every one of our readers is “Defying the Odds. The Rise of Dalit Entrepreneurs” by Devesh Kapur, D. Shyam Babu and Chandra Bhan Prasad; Publisher: Random House, India.

This extraordinary book tells us how Dalits, who have been for centuries suppressed by a stultifying societal identity can liberate themselves as individuals and as individuals how so many of them have literally and metaphorically defied the odds and emerges ad successful entrepreneurs. It is not state hand-outs or government doles that have been the key to the lives of these remarkable persons. It is the call of the free market where the high quality of your product and the attractive price of your service determines whether you succeed, not what surname you carry or what accent you speak with, which caste you belong to or which college you have attended.

It turns out that the best cure for centuries of deprivation is simply having the right of free and unfettered entry into business–a right not granted based on birth or connections, a right not granted at all, a right that is grasped by sheer ability, resilience, chutzpah, risk-taking and hard work. No one turns down a good job in a factory merely because the owner is a Dalit; no one refuses a good bargain that is seen in a product or a service, simply because the company providing the product has been started by a Dalit.

The book is of course, inspirational–just as the biography of any Ayn Rand heroic protagonist would be. But it is also dedicated to the simple proposition of empirically verifiable consequentialism that a free market is the best antidote to entrenched casteism. Remember that in the permit-license Raj, only the well-connected get licenses. But when you no longer need the state’s permission or license to start and run a business, guess what, out of the woodworks dozens, hundreds, thousands of Dalit entrepreneurs emerge.

As we engage in political and polemical discourse in the years to come, between Ayn Rand and the biographies of Dalit entrepreneurs, we have powerful weapons in our armoury to encourage our young to turn their gazes and give their support to robust individualism, free markets and the resultant enhancement of freedoms for all humans.