BJP Banks On Modi Miracle In Maharashtra

The Swarajya-5Forty3 pre-poll survey finds that Modi is cashing in on a feckless and fractured opposition in Maharashtra.

“Every time we see an advert of Pradahan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana on business channels like CNBC Awaaz or ET NOW, we can’t help but laugh at the Modi government’s stupidity… tell me why would a guy without even a bank account be keeping tabs on the share bazaar?” asks a young man from Kolhapur in western Maharashtra.

It is indeed difficult to find a rationale for some of the government’s decisions, let alone trying to explain the logic of government ad spends. How the government spends its advertising rupees might have been a trivial matter in the years past, but a young man from the hinterland asking such probing questions is symbolic of a new networked India.

It is not as if that the financial inclusion drive Jan Dhan Yojana is simply another madcap scheme from Dilli. It has indeed been well received by its intended beneficiaries. Nearly six out of ten people in the three districts of western Maharashtra that we surveyed had heard about the scheme, which in itself is a great beginning for something which was only conceived and rolled out about a month ago. The message from Maharashtra is something else. It is perhaps a reminder to Modi that India doesn’t expect the same lazy approach to governance, and the advertisements on business channels are merely symptoms of that laziness.

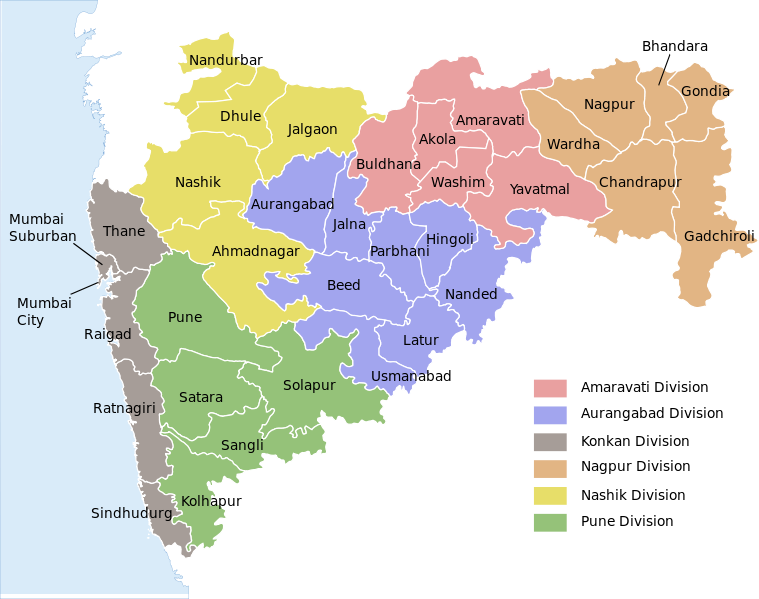

When we first visited Western Maharashtra during the Navratri season, the mood on the ground was quite sombre. It looked as if the decades old status-quo had sapped people’s energies. The deeply entrenched cooperative lobbies, the sugar barons, the education entrepreneurs and the ecosystem of self-aggrandizement that has come to define Sharad Pawar’s politics, looked set to prevail yet again in this part of the world. Neighbouring districts of Marathwada looked no different, as the main contest appeared to be developing between Congress and Shiv Sena; there was even talk of a grand revival of the sinking Congress ship in the waters of Bheema (in Marathwada).

The scenario that was unfolding in front of our eyes in Maharashtra was eerily similar to Chhattisgarh last year. Many people do not realize this, but the turning point of Indian electoral history in 2014 actually came in late 2013 in the small tribal state of Chhattisgarh. After the first round of polls in Chhattisgarh it was amply clear that Congress was winning the state. That would have been a major jolt for the BJP – losing a state to the Congress party so close to the LS polls. Before the first round of polls in southern parts of Chhattisgarh (Bastar and Rajnandgaon divisions), Modi had addressed a few rallies, but to many people’s surprise there were no takers in this tribal region for Modi. While on the other hand, Rahul Gandhi was getting a lot of enthusiastic support wherever he travelled.

It was at this make-or-break moment that Modi decided to up the ante and he addressed eight back-to-back rallies mainly in the central parts of Chhattisgarh before the second phase of polling. His speeches were passionate, his connect with the crowd was excellent and his appeal, although universal, was also more specific to the largest block of OBC voters, especially the Sahus of central Chhattisgarh. Those eight rallies turned the tide for the BJP as the Sahus and the OBCs voted overwhelmingly in one direction and BJP managed to scrape through to form a government. Modi had rediscovered himself at the national stage, beyond his comfort zone in Gujarat. From that moment on there was going to be only one man everywhere in the 2014 general elections. The rest as they say is history.

We conducted a unique experiment of a before-after (Modi rallies) random tracker poll survey in three districts of Marathwada with a target sample-size of 1500 (achieved: 1339 and 1306) and two districts of Western Maharashtra with a target sample-size of 960 (achieved: 891 and 870). The survey was done carefully choosing the demographic in swing polling booths of each district giving adequate representations to various caste and social groups using our proprietary Voter Weightage Index Sampling Methodology (VWISM).

The results were staggeringly clear about one man’s hold over popular imagination of those regions. Let me put this in the words of that young man from Kolhapur who had groaned about the government ads on business channels. He had surprisingly turned to the BJP camp in less than a fortnight, by the time we revisited Kolhapur on Wednesday last. “What has Sharad Bhau (Pawar) given us in four decades? We cannot ask for ‘hisaab’ from Modi in just four months… besides, look at Modi’s popularity even in New York, everybody believes in him!”

This mass hysteria with anything connected to Modi is the reality today. He just has to travel to your part of India (or the world, as the New York sojourn suggests) and you start talking his language and asking the questions of other politicians he wants you to ask. His speeches seem to leave the opposition demoralized. An astounding 12% plus increase in vote-share post the campaign rallies of one leader is simply unheard of in the post-Indira Gandhi India.

What is it that Modi does to have such a far reaching impact? At the outset the most important achievement of a Modi visit is that it changes the discourse in the region or district. More importantly Modi frames the debate in favour of the new aspirational India (which constitutes about 60-80% of Indian populace today) and breaks down his development message in a language so simple that it is hard not to believe him.

For instance, in Kadegaon (Sangli district) most political discussions in September were centred on one man, Patangrao Kadam, the Congress stalwart who is one of the CM aspirants in the party and also runs the education industry behemoth ‘Bharati Vidya Peeth University’ which operates many medical, dental and engineering colleges in and around Pune. By early October, after Modi’s rally in the neighbouring town of Tasgaon (RR Patil’s constituency in Sangli district), most public discussions and street corner political debates had shifted to Modi and his message seeking a majority in the assembly for the BJP so that Maharashtra can derive the maximum benefit of jobs, electricity and better roads etc.

As we understand it, the impact of Modi rallies is three-fold;

- The primary effect is on the undecided voters or fence-sitters of that region who simply make their decision to vote for Modi’s party/candidate discarding all local/regional considerations

- The secondary effect is on BJP’s core-voters and party workers who get charged up after a Modi campaign and make that extra effort in the last few days before polls

- The tertiary effect is the negative impact on the core opposition voters and opposition party workers who abruptly begin to lose faith in the chances of their victory (one example of this was a sudden disinterest among Muslim voters in Usmanabad district after the Modi rallies in Marathwada, which is what we observed even during the LS polls in the summer of 2014 in Rampur of Uttar Pradesh and Gulbarga of Karnataka.

Yet, there is more to this miraculous BJP turnaround in Maharashtra, a state where BJP has never won more than 65 seats in its history and a state which hasn’t seen a single party victory since 1990 – a double obstacle that must be surmounted. Despite the stupendous victory in the LS polls, what the BJP is attempting defies logic. The party, from a mere 46 seats, is trying to virtually triple its tally without adequate ground staff. It is clear that the BJP lacks grass roots workers and cadre in more than 100 seats that it is contesting, yet the party is dreaming of emerging victorious riding on the popularity of one man.

In the last four assembly elections, BJP had a constant vote share of 14% and it doubled in the LS polls when the party secured 28% of the popular vote, but will that be enough now? Firstly, BJP is now contesting more than double the number of seats it contested last time (119) and then it doesn’t have the support of the Shiv Sena cadres to reach out to the voters.

To understand the difficulty of achieving a single party majority or near majority, we must consider the following statistic. In the 2009 assembly, there were 103 seats which were decided by a vote margin of less than 10,000 votes or roughly under 6% vote margin (barring a couple of low turnout exceptions). Of these 103 seats, 16 belonged to BJP, so this time BJP has to first defend these 16 low-margin seats and then try and win at least 60 of the remaining 97 close contests of 2009 in order to get a clear mandate. We must also remember that last time was a straight contest whereas this time it is a multi-cornered battle. So victory margins could be even lesser. The silver lining for the BJP is of course that more than 50 of these close contests were won by either Congress or “others” who are the most vulnerable parties in this election under the Modi onslaught.

Yes, I was a skeptical about BJP’s strategy of going solo in Maharashtra. I felt they were committing electoral hara-kiri and expected a severe drubbing for the party. But when the data started to emerge post the Modi rallies, I was taken aback. Apparently, a lot of strategic thinking has gone into the decision to break the 25-year-old alliance, ticket distribution and the Modi messaging. Let us consider the following five paradigms;

1. Last minute breakup of alliance by BJP gave very little time for a realignment of regional parties like NCP, MNS and Shiv Sena who would have probably grouped together formally had the breakup happened a couple of months earlier.

2. Consider this: There have been two types of electoral battles in India in the Modi era– BJP vs Congress and BJP vs regional parties. While the former has produced only one kind of result–a victory for BJP and decimation of the Congress, the latter has been a mixed bag of either BJP winning big like in the heartland or the regional party deriving the maximum benefit of BJP’s ascendancy as seen in Odisha, TN etc. Amit Shah seems to have learnt his lessons from 2014 so his strategy in Maharashtra is twofold. In regions where the contest is directly between Congress and BJP, like say, Vidharba, BJP’s game plan is straightforward. But in areas where the contest is with regional parties, like say in Western Maharashtra, the plan is an adaptation of UP-Bihar model of building small localized coalitions by bringing in locally powerful leaders into the party fold. Thus a large number of NCP-Congress and even some Sena rebels have found acceptance in the BJP in Marathwada and western Maharashtra.

3. In the last 65 years, elections have almost always been won by winning rural India because the political current has always flown from the villages. For example, take the 2004 national elections when the Vajpayee led NDA suffered an unexpected defeat not because of bad governance but simply because of rural distress due to a humungous drought in 2002-03. In 2014, for the first time, in a vastly connected India, political current is flowing from urban India. BJP and Modi have recognized this change while other parties are still stuck in the rural paradigm of pork barrelism and caste calculus . One simple metric for this is how rural India reacts to Modi’s easy to assimilate messaging on job creation and reliable power supply. This is what a young man from a village near Nanded had to say: “I am not educated, although I can read and write, but I know I wouldn’t get a decent job in the city so I never thought of leaving my village… Then I heard our PM on TV talking about how India requires millions of skilled drivers today while many million youngsters are sitting jobless. Modi talks about bringing together these high paying jobs and the jobless youth and also wants to setup driving schools everywhere… I am now really excited about this prospect”

4. Another dramatic shift that is happening in India today is in the realm of political structure. Since the late 1980s India has essentially been built on a bottom-up political structure, wherein electoral experimentation has always first started at the local/state level and then replicated nationally. One consequence of this phenomenon was that local satraps were of immense importance for the political growth of a party. Thus in the last 20 odd years we have seen some very powerful Chief Ministers who virtually ran their states independently. BJP adapted quite well to this federated political structure and gave rise to many powerful state leaders, but Congress struggled to internalize this political reality and started to lose its base in a vast number of states (not the least in the heartland). Now the tables have turned, Congress is finally getting ready to adapt to a federated political setup, while India, dare I say, has entered a new cycle. Today the Indian political structure is increasingly resembling a top-down system wherein the national is the new local. Chief Ministers are slowly losing their primacy. BJP is going into both Maharashtra and Haryana state elections without a chief ministerial face and this could be the way forward. What matters now are issues of governance and working in tandem with the centre, or as PM Modi puts is succinctly, “State government and centre should be ek aur ek gyarah, not ek aur ek do”!

5. The demographic dividend is constantly repaying Modi with interest many times over. Yes, we seem to be truly entering into a post-caste electoral system. The old way of simplistically analysing election outcomes based on caste-vote matrix is almost dead now as a vast section of young voters simply refuse follow the caste fault lines. Surprisingly, the pioneers of this new casteless vote system are not upper castes or even the middle castes, but the Dalits!

What we see today, especially among the young Dalit voters is a willingness to experiment beyond their traditional leadership and embrace Modi’s politics of development. Once again, the actual understanding of this vote shift phenomenon comes from the ground, from a small time Dalit entrepreneur in Dhule: “We get education, yes, because of reservations. But the government jobs have dried up long ago. Do you know how many years an average Dalit youth has to wait after his education to get a half decent job?” No wonder there is a clamour for reservations in the private sector too, but more importantly there is a realization among the Dalit community that reservations do not guarantee social mobility and what they want is Modinomics of faster growth and a larger job pool.

The only other pan-Maharashtra party today is the Congress party, but it is a party in almost terminal decline and is facing a triple whammy of sorts. At one level the Congress is facing massive anti-incumbency both nationally as well as in the state, but what is even more worrying for the party is that its candidates – many of whom are local stalwarts who could in the past win elections purely on their own might – are today facing strong local rebellion. At another level the party’s campaign has been very lacklustre with hardly any participation from its national leadership which seems to be still reeling under the impossibly huge defeat in the LS polls. Finally, at the ground level, a large number of party loyalists and workers (at the zilla parishads, panchayats and wards) simply lack the will to fight a losing battle.

Congress is the principal opponent of BJP in Marathwada and Vidharba, the two regions where BJP’s performance is probably going to be at its best. In western Maharashtra, where Congress depended on Pawar’s sugar lobby in the past elections, the party is suffering a virtual rout, whereas in Konkan it still has a chance to come up with a half decent performance. What is really going to punish the Congress the most is the extreme anger of the urban and town voters who are simply in no mood to forgive the party (surprisingly even Muslims are angry with the party but they may at best stay away from voting).

Once again, we found that one of the biggest issues in towns and cities was lack of electricity. It is indeed criminal that such an urbanized state like Maharashtra should face such a massive power shortage. Very few outsiders know this, but six-to-fourteen hour blackouts are pretty much normal in Vidharba and Marathwada! Simply, how can the Congress go to the electorate after 15 years of being in power with such a disastrous performance on this front?

The primary problem for a party with such a widespread base is that its seat conversion ratio would always be abysmally low, so even with 19% vote-share the party could win only 44 seats in the Lok Sabha, while parties like Trinamool Congress and AIADMK could win 34 and 37 seats with as little as under 4% vote-share. This is replicating in Maharashtra too, where there is a possibility that the party could still be a distant number two in terms of vote-share but may end up fourth in terms of seats.

These are the dangers of being excessively reliant on the Muslim votebank. We had warned about this last year during the assembly elections in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh and had first demonstrated the downfall of the party using clear electoral data but the party is only slowly waking up to this reality as is evident from the A.K. Antony report after the May 2014 debacle. Muslim vote on its own cannot win seats without incremental addition of votes from other segments of the society. The Congress party desperately needs to internalize this reality and arrest its own decline, lest it completely disintegrates in the coming years.

If the Congress is handicapped by spreading thin, the regional Maratha parties are suffering because of lack of base outside their strongholds. While NCP is unviable as a political entity outside Western Maharashtra today, Shiv Sena is mostly a Mumbai-Konkan Party with some scattered base in parts of Marathwada. Ideally, since mostly their votes are sub-regionally symbiotic, apart from MNS and Sena in Mumbai region, these three regional parties could possibly come together to form a united Maratha entity which could be a far more viable electoral experiment, but unfortunately we don’t live in an ideal world and political egos in India only rationalize after the sun sets on their individual political careers (Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad being prime examples).

There are roughly about two crore Maratha voters in Maharashtra, about 25% of the total electorate, but it is hardly a monolith which has made it difficult for a single Maratha political party to thrive, unlike say the Yadav parties of the heartland or even the LIBRA (Lingayat-Brahmin) experiment in neighbouring Karnataka from which Ramkrishna Hegde and BS Yeddyurappa derived their powers. For instance, one of the reasons for NDA’s defeat in the 2009 LS and assembly polls (at least in Mumbai and surrounding regions) was mainly because the Maratha vote got divided due to Raj Thackeray. Today, ironically, the same Raj Thackeray is a blessing in disguise to the BJP. In fact, it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to suggest that the number of seats BJP wins in Mumbai could be directly proportional to the performance of MNS as it hurts Sena the most. Thus the joke in Mumbai today is that “the more Raj Thackeray gets belligerent and the more he attacks BJP and Modi, the bigger the damage to Uddhav”.

The Swarajya-5Forty3 team travelled extensively in 14 districts of Maharashtra for an exclusive pre-poll survey covering 236 swing polling stations spread across 61 assembly segments of all the different subdivisions of Maharashtra. We conducted this pre-poll survey in two phases in late September and from October 4th to October 10th in order to gauge the mood of the voters and the shifting vote patterns.

The target sample size for this survey was 7600 with adequate representation given to various social/caste groups (using VWISM) and maintaining an urban-rural divide ratio of 42:58. Thirty two trained data collection officers travelled to pre-determined swing polling booth areas and conducted specific interviews of pre-selected random target individuals and families gleaned out of electoral rolls provided by the election commission. Each data collection officer had a mandate to interview only 40 target individuals each day, thereby ensuring adequate “spacing out” in our sample survey which helped us remove over-representation of data in certain regions or of certain social groups (lessons learned from the 2014 LS poll sampling errors).

We achieved a sample-size of 7148 (exclusive of around 2400 repeat sampling done for the “before-after” experiment) across Maharashtra. We then parsed the collected data through our statistical modelling systems to remove whipsaws and to adjust for pre-determined weightage. (One of the major new tweaks we have incorporated in our statistical model is to assign decreasing proportional ratio to BJP as the dominant party which tends to get over-represented in sample surveys).

Despite all our efforts there is always a possibility of error in any sample based survey as it does not represent the whole. Based on our past experience we have assigned international pre-poll standards of 3% error possibilities to this survey.

1. BJP (with its smaller partners) enjoys a clear 15% lead over its nearest rival Shiv Sena in the state which is a logic defying margin in a large state with 288 assembly seats

2. BJP has a clear, almost double-digit, lead across all the subdivisions of the state, except for the smaller Konkan region where Sena is ahead and in Mumbai where BJP’s lead is smaller

3. There is a battle for the second place (in terms of vote-share) between Congress and Shiv Sena, and although the latter enjoys a clear edge, it still remains within the error margin (of under 3%)

4. In Vidharba, Marathwada and Western Maharashtra (178 of 288 seats), BJP currently enjoys a clear lead of over 10% which usually must translate into a strong sweep of these regions

5. The real battleground could be the Mumbai region where there is a 5 cornered (in some cases even 6 cornered) fight which makes predicting the outcome very difficult

6. In Mumbai, there is also the battle of the demographic between Maratha and non-Maratha voters; whilst BJP is clearly benefitting by breaking its alliance with the SS by garnering all the non-Marathi vote (except for the Muslim vote), Congress/NCP once again seem to be the bigger losers

7. Dalit vote could be the crucial deciding vote in many assembly segments in Mumbai and surrounding regions

8. Overall vote-share of MNS in the state is less than 4% so it doesn’t merit an independent space in our analysis

10. The one primary X factor now is the actual turnout, which could decide whether these percentages really hold. Our systems (with the error margins, we must stress) should hold in the event of any normal electoral turnout of 55% to 65% range, but if the turnout is in the extremes, below 50% or above 65%, then these pre-poll survey numbers may undergo dramatic changes

11. There is also a second X factor of the possibility of regional and smaller parties having a tacit understanding just before polling in order to avoid vote-splits; for instance, there are some rumours of MNS and Sena trying to work out a formula of helping each other in and around Mumbai to stop the BJP juggernaut, although it remains to be seen how effective such a last minute understanding could be

This is where the real election analysis should ideally end, with the release of vote-shares, because seat conversion is a dark art in the Indian context as there is no fixed mathematical construct to derive seat numbers from. Most of the errors occur in converting votes to seats, for instance, we were almost 93% accurate in projecting vote-shares in both the 4 state assembly polls of November-December 2013 as well as in the summer LS polls of 2014, but most of our errors occurred in seat-share projections. It is next to impossible to derive seats from the vote-share numbers in multi-cornered contests, yet any election analysis would be incomplete without allocating seats to different parties.

The bottom-line is that BJP should end up as the single largest party and also possibly with a very clear mandate if not a thumping majority in the Maharashtra assembly. The reason for this is fairly simple, as it looks unlikely that BJP will get anything less than 100 seats out of the 178 in Vidharba, Marathwada and Western Maharashtra, so that leaves the party with the target of just about 40% in the remaining 110 seats to win. What is even more difficult is projecting seat-shares of other parties, as their vote is scattered and there are no fixed sub-regional formulae to fall back-upon. With all those caveats, we are trying to be brave and project how the new assembly is likely to look in Mumbai after the 19th of October.

{Disclosure: The Swarajya-5Forty3 survey was neither funded nor sponsored by any political party or political organization and the entire exercise was done independently. We incurred a cost of roughly Rs 65 per response for the survey (almost half the price of standard industry cost). Three sources of income funded the survey. Some members of the 5Forty3 ground team conducted constituency level surveys for five individual candidates and the resultant profits were re-invested to conduct the statewide survey. We conducted some surveys for a Mumbai-based brokerage firm which was our second source of capital. The remaining capital requirements were met through internal resources. }