Swarajya-5Forty3 Haryana Survey: BJP In Pole Position

Non-Jats and Dalits are consolidating firmly behind the BJP, and young Jat voters are responding enthusiastically to Modi’s politics of vikas. It’s clearly Advantage BJP in Haryana, finds the Swarajya-5Forty3 pre-poll survey.

Sir Chhotu Ram (the first Stephanian to be knighted in 1937) was the original political visionary of Haryana when he built his almost unassailable social coalition of AJGAR – Ahirs, Jats, Gujjars, and Rajputs – which helped his unionist party to win the 1935 elections and form the provisional government of Lahore in an undivided Punjab that also included the yet to be crafted state of Haryana.

Sir Chhotu Ram’s grandson, Ch. Birender Singh, had the same knack for catching political signals from the ground, but he unfortunately didn’t have his grandfather’s luck.

So, in 1991, when as the state president of Haryana Congress, Ch. Birender Singh, selected a virtually unknown “Bhupi” to contest against the mighty Devi Lal (former deputy PM) from Rohtak Lok Sabha seat, many political pundits were surprised by his choice. It was literally a lopsided contest between a giant and a novice, but Sir Chhotu Ram’s grandson knew that the AJGAR coalition could perform miracles even after 60 years. Bhupi, ‘the political novice’ won Rohtak by a margin of 30,000 votes in 1991 and further went on to inflict a hat-trick of defeats on Ch. Devi Lal in 1996 and 1998.

The almost meteoric rise of Bhupi aka Bhupinder Singh Hooda in the political landscape of Haryana had altered the social dynamics of the state. All through the 1970s, 80s and 90s, Congress was the non-Jat pole of Haryana polity, while Devi Lal and his clan represented the Jats, initially through the Janata Dal and then by forming their own regional outfit. After winning the 2005 elections in the state, Congress took a bold decision of not giving the reigns of the state to Bhajan Lal and instead chose a Jat to be the CM which has given them rich dividends, both literally and figuratively, in the last decade.

While both Hooda and the Chautalas targeted the Jats over the last decade, there was a certain vacuum in the opposition political space which is what BJP filled so successfully in the summer of 2014 by not only winning 7 LS seats but also leading in 51 assembly segments. That is an astounding piece of statistic, mind you, for a party which had a paltry 4 seats in the previous assembly and had almost never managed to get double-digit voteshare in the assembly elections (except for 1987 and 2005 when it barely touched 10%). This quantum leap in BJP’s voteshare (a rise of 250%) in the LS polls just a few months ago gave us an indication of the political shift in the state.

Today, Ch. Birender Singh, shrewdly sensing the signals from the ground, has shifted to BJP after a four decade long career in the Congress party and with him he brings his grandfather’s legacy. Today in Haryana there is another social coalition that is quietly shaping up – GADAR – Gujjars, Ahirs, Dalits and Rajputs are all making common cause with the two ‘B’s, Brahmins and Banias, forming a single block of 37% votes in Haryana (Jats are roughly 23% in the state). In simple words, this is nothing but another example of the post-caste electorate of India, for even Jats are no longer a monolith supporting only one political entity.

The theme is again the same even in a veritable caste conundrum like Haryana–faster development and higher aspirations. The young are the most restless, be it in the cities or in the villages. To be fair to the incumbent CM, the pace of development in the state is pretty decent; urban infrastructure has seen a drastic change in the last 10 years, while even agrarian distress is hugely reduced due to much better irrigation systems. In the normal political course, Hooda should have even gone on to win a third term without really sweating it out.

What is hurting Hooda the most is his own party and the party bosses. Anti-Congressism is so deeply entrenched in India today, especially in urban India that the party gets no incremental votes whatsoever. As a prime example of what is happening in Haryana, let us consider the plight of his party in Hooda territory. Congress had managed a clean sweep in Rohtak by winning all the nine assembly segments in the last elections, while this time Hooda is facing rough weather in six seats and may not end up winning more than three or four.

If such is the plight of his party in his home district, one can imagine the kind of political atmosphere in the state today.

If the LS poll results were to be replicated, then the outcome of this election would have been reasonably straightforward with BJP getting a clear majority. But has the situation remained the same since then?

For starters, assembly elections bring in a great deal more sub-regional and even intra-district dynamics out into play than say in national polls. Then, there was the factor of the jailed Chautalas for whom this is a do-or-die battle, for if they lose this election, INLD may even cease to exist in five years’ time. Also, the fact that Bhupinder Singh Hooda did put up a valiant rear-guard battle almost singlehandedly, may have made some difference to the political configurations.

There are two ways in which we can try and decipher Haryana’s politics today – one is the top-down approach by taking a snapshot of the state on the whole and the second is the bottom-up approach by trying to analyse the sub-regional and inter district political dynamics. Let us try and understand both the systems to arrive at the final numbers.

Demographically Haryana is divided into four major strands – the upper castes constituting about 20%, the middle caste of Jats accounting for 23%, the OBC strand of 25% and the Dalit populace of 22%. What is clear from the above chart is that no single group can provide electoral victory on its own without incremental addition of votes from other castes or groupings. This is the primary reason why INLD’s upside threshold potential has been historically limited to under 30% due to its inherent inability go beyond the Jat demographic – the highest that INLD got was 29% voteshare in 2000. Congress’s strength so far has been its ability to garner large portions of upper-caste and OBC votes along with a section of Dalit votes, to which Hooda had managed to add the Jat dimension thereby creating an unbeatable social combination.

How has the emergence of BJP altered the caste calculus of Haryana? In order to understand this, we conducted pre-poll survey in 13 assembly segments of 5 parliamentary constituencies with a target sample-size of 3000. Through October 4th to October 12th, about 12 of our trained field officers travelled across the state to visit 65 polling station areas and interviewed voters with specific pre-allocated questionnaire. Swing polling booths and target respondents were carefully chosen using our proprietary sampling system VWISM (Voter Weightage Index Sampling Methodology) by creating subsets using electoral rolls provided by the election commission.

Each field officer was allocated only 40 respondents to be covered each day in order to ensure adequate ‘spacing out’ of our demographic sample and also to ensure higher interviewing standards.

It is quite clear that BJP has emerged as the number one choice of all the non-Jat groups and most importantly it is laying claim to almost the entire Dalit vote left behind by a declining BSP and a moribund Congress party. Yet, there is more to this picture than what the graphic suggests. Dominant middle-castes in India have both the militant capacity and intellectual ability to drive the voteshares of their preferred political parties by sheer force. For instance, Yadavs in UP or Marathas in Maharashtra or Lingayats and Vokkaligas in Karnataka have the ability to simply add 10 to 15% additional votes purely because of their dominant status in the villages.

Some of this capacity is through positive convergence, wherein smaller caste groups in a village setting make common cause with the dominant middle castes on polling day in order to avoid day-to-day confrontations. But there is also a negative aspect to this phenomenon, wherein marginal castes, especially Dalits, are coerced or prevented from voting in large numbers by strong arm tactics. Thus when we create a caste-snapshot based on survey data alone, we must also factor in these issues and give additional weightage to dominant middle castes.

What was also evident in our survey was the perception among the voters about BJP not being a Jat-centric party while both the opposition parties are going into battle with Jat faces as their leaders, thus by inadvertently not naming a CM candidate, BJP has ensured support from most non-Jat groups in the state. Main problem with Congress was its inability to shrug off anti-incumbency and an unwillingness by voters to waste their vote on a losing horse. INLD’s presence was stronger in villages and rural Haryana, especially in the Jat belt, which could be one of the reasons why the party may get under-represented in sample surveys, although we did maintain a 45%:55% urban-rural ratio in our sampling methodology.

Haryana has a total electorate of 1.62 crore voters. Assuming a turnout of roughly 70% (which has been the norm in the state in recent times) and further discerning that the Dalit vote would be underrepresented (due to historical factors), it would still mean that anywhere between 20 to 24 lakh Dalits would have cast their votes on the 15th. Now consider this, Congress got a total of 33 lakh plus votes in 2009 and emerged to form the government in the state! This should give us an idea of how crucial the Dalit vote would be for the assembly elections this time, considering that they are the single biggest non-Jat entity in Haryana and there is no BSP to reckon with this time.

Electorally, Haryana is divided into two parts– the Jat belt comprising of the Hissar-Rohtak divisions and the non-Jat belt made up of Ambala and Gurgaon divisions. The Jat heartland is home to 39 assembly segments spread across eight districts whereas the non-Jat belt consists of 51 assembly segments.

BJP had led in 32 of the non-Jat assembly segments in the 2014 LS polls, which should act as a good base even in the assembly elections.

Till now, the key to winning Haryana was by maximising the Jat seats and then winning incremental seats in the non-Jat belt to get a majority. For instance even in 2009, Congress had won 20 of the 39 Jat heartland seats (nine in Rohtak alone) which helped it become the single largest party. This time though, what BJP is attempting is the exact opposite, it is trying to win maximum non-Jat seats and then gain some in the Jat heartland. Thus BJP needs a strike-rate upwards of 60% in the Ambala-Gurgaon subdivisions in order to emerge with a clear mandate in Haryana.

In Sonepat, Rohtak, Jhajjar, Hissar and Bhiwani etc. Jats constitute as much as 33-45% of the electorate and thus calling the shots on polling day. Yet, for a party like INLD, which is handicapped by its inability to get non-Jat votes, the dependence on division of opposition votes is the key. So INLD’s performance in these Jat dominated districts, apart from Rohtak and Jhajjhar where Congress is still a strong player, would ultimately be proportional to the amount of votes that Congress can garner.

Our own survey in these parts has indicated that Congress is a distant third in many key seats (again apart from Jhajjhar and Rohtak) which could lead to an interesting straight fight between INLD and BJP – essentially Jat vs non-Jat direct fight. There is also the possibility of tactical voting by Dalits in order to support the best suited candidate to take on the Jats.

In the more urban centres of Gurgaon, Panchkula and Ambala etc. BJP seems to be enjoying a clear advantage over other parties as even a section of young Jats are swayed by Narendra Modi’s development pitch. The interesting takeaway from the LS poll lead positions is that Congress was ahead only in three out of the 51 non-Jat seats, while BJP led in 32 which also corroborates our own finding of BJP being the number one choice among non-Jat voters.

Ergo, even if INLD has improved its position since the Lok Sabha polls by garnering Jat sympathy, its upside potential being limited, BJP is still in the pole position. As we see it today, the key battles could be fought in four districts – Bhiwani, Mahendragarh, Sonipat and Hissar. Whoever wins the maximum seats in these districts could enjoy an upper hand.

Taking all these broad caste-social factors and specific sub-regional aspects into consideration we devised our unique statistical model for Haryana to parse ground data in order to arrive at the weighted numbers. Once again, special proportional ratio reduction of BJP respondents was given extra weightage in order to remove whipsaws of the dominant national political party. Eventually, we had achieved a sample size of 2760, which is reasonably adequate for a state the size of Haryana. Out of those 2760, 1159 were women and 1601 men. That too is a reasonable gender distribution for a male dominated state such as Haryana.

Our eventual findings seem to be consistent with the historic behavioural patterns of the Haryana electorate. A Jat Based party like INLD has always consistently performed in the early to mid 20% voteshare range, in line with its core vote bank. The variation occurs in opposition voteshare, which was largely represented by Congress in the past and is now being occupied by the BJP. In the current elections there are three major X factors;

X factor 1: As always the turnout figure will give us the greatest possible indication of how far our projections would hold true. What is of significance is the turnout differential in the Jat dominant areas vis-à-vis the non-Jat dominant areas that will give us a fair indication of the “hawa”.

X factor 2: The Chautalas going to jail is a double-edged sword. There could be both sympathy for them from the Jats as well as a sense of dejection which could turn many young voters (even among the Jats) to not waste their votes on a party that may not be in a position to govern (in the later part of our survey, on last the last days, there was a hint at the latter).

X factor 3: Winner takes it all syndrome of Indian elections may help BJP in the last two days as a majority of the fence sitters tend to choose the leading party while voting.

It has now almost become customary for the Indian voters to give a clear mandate for a single party (or a pre-poll alliance). Voters want better governance and greater accountability. Data shows that since the turn of the century, 96% of all election verdicts in India have been either a majority or a near majority. Albeit, most psephologists tend to undermine this basic statistic when they throw out numbers based on hard data. Thus we have every election survey in town presenting their own version of “hung assemblies” in both Haryana and Maharashtra, disregarding basic voter intelligence which has been overwhelmingly in favour of clear mandates, including the biggest one in the summer of 2014.

Yet, in the last 15 years, one of the rare fractured mandates was given out by voters of Delhi last year. And since Haryana is the geographic neighbour and has some similarities in terms of social base and upward mobility to Delhi, the possibility of a hung assembly cannot be altogether ruled out.

Also, we must remember that even in 2009, a Hooda led Congress did not actually win a majority on its own, although it was clearly placed at the top to form a government. Thus Haryana may throw up a quasi-hung assembly and surprise us all, but the bottom line is that BJP would be the single largest party in all likelihood. Even in the worst case scenario for the party, it would only be a whisker away from a majority. In fact, if any party seems to be in a position to achieve a majority, it is the BJP.

The campaign trail itself had a story to tell. Prime Minister, Narendra Modi addressed 12 massive public rallies covering all the important parts of the state. Even Amit Shah addressed some 22 rallies, while a weary Bhupinder Hooda was the Congress’ Rock of Gibralter. INLD was of course handicapped by its top ledarship’s legal wrangles.

As a result the BJP had a huge advantage in occupying the voters’ mind-space. That, combined with the message of development, and the performance of the central government, should provide a much better ratio of incremental votes for the BJP.

Once again, the reluctance of the Congress party, especially the Delhi elite, to even put up a fight came as a surprise. Sonia and Rahul Gandhi together addressed some five lacklustre public meetings in all. It looks like Sonia and Rahul have lost the will to fight and if this attitude continues, the grand old party could well implode.

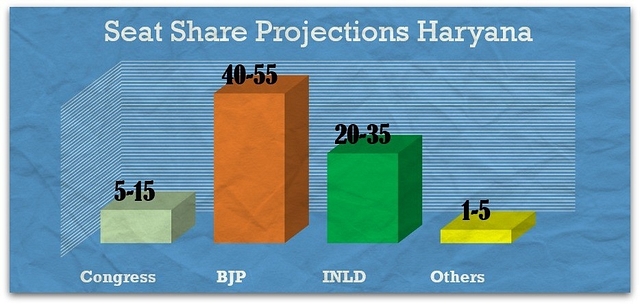

Once again with the caveat that vote to seat conversion in India is almost a dark art with no solid mathematical foundation we (most reluctantly) give out the possible seat-share ranges based not just on overall voteshares but a careful assessment of sub-regional dynamics. These seat share ranges are simply a representation of worst and best case scenarios for each of the parties/groups.

{Disclosure: The Swarajya-5Forty3 pre-poll survey was not sponsored by any political party or funded by any political organization either directly or indirectly. We incurred a cost of Rs 50 per response in Haryana as it is a much smaller state with lesser travel expenses. Some 60% of the overall cost was covered by income from conducting poll surveys for two individual candidates and interpreting data for them. The remaining 40% of the expenses were met through internal sources.}