Ramachandra Guha On C.Rajagopalachari – Part 3

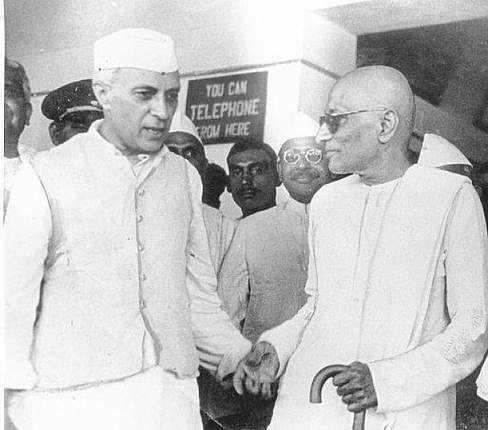

Nehru and Rajaji were comrades rather than companions. They were separated by upbringing; one was an aristocrat educated at Harrow and Cambridge, the other a self-made man from small-town South India. They were separated also by a thousand miles of peninsula.

(This is the last part of a 3-part series. Here are links to the first and second part)

RAJAJI AND NEHRU

In the course of the past year or two, I have spent many absorbing days looking at the Rajaji papers, housed at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library in Delhi. This vast collection contains original letters from world statesmen as well as by unknown Indians. Sometimes the latter are as interesting and insightful as the former. Consider a letter to Rajaji written in 1953 by a mofussil Tamil named Anantharaman. This offers the view that Rajaji, Nehru and Patel were, respectively, the ‘head, heart and hands of Gandhiji’.

This is most appositely put. For Rajaji was unquestionably the most intelligent of Gandhi’s close disciples, Nehru arguably the most humane, and Patel the most disciplined and practical. The pity is that they could never function together except for a very brief while. The relationship between Nehru and Patel has attracted much attention. Here I focus on the no less intriguing relationship between Nehru and Rajaji.

During the freedom movement, Nehru and Rajaji were comrades rather than companions. They were separated by upbringing; one was an aristocrat educated at Harrow and Cambridge, the other a self-made man from small-town South India. They were separated also by a thousand miles of peninsula.

In terms of ideology too there were differences: Nehru was more inclined to militant socialist views, Rajaji more oriented towards accommodation with the adversary. But they were united by a shared ideal—the freedom of India—and a shared devotion to the Mahatma. (It was Rajaji whom Gandhi first designated as his successor, later changing his mind in favour of Nehru.)

They met at Congress meetings, but did not seem to have been especially intimate. Still, the Tamilian had impressed Nehru enough to have him write in his autobiography of how Rajaji’s ‘brilliant intellect, selfless character, and penetrating powers of analysis have been a tremendous asset to our cause’.

It was from 1946 that the two men began to work more closely together. In the next eight years, while Nehru was Prime Minister in New Delhi, Rajaji was, successively, a Minister in the Interim Government, Governor of Bengal, Governor-General of India, Minister in the Central Government, and Chief Minister of Madras State. In all these jobs he had direct and regular dealings with Nehru.

But official business drew them closer at the personal level too. The two men shared a cultivated interest in literature and the arts: it was only to Rajaji, and to no other Congressman, that Nehru could write recommending a recent book on the British character by the anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer or praise the beauty of the folk traditions of India.

After a visit to the north-east, the Prime Minister wrote to his Southern colleague about the ‘most lovely handloom weaving’ he had seen there. He confessed to being ‘astonished at the artistry of these so-called tribal people. I think it will be disastrous from many points of view to allow such an industry to fade away’. ‘Altogether my visit to these north-eastern areas has been most exhilarating’, wrote Nehru to Rajaji: ‘I wish they were better known by our people elsewhere in India. We could profit much by that contact’.

Reading the correspondence between these two men, I was deeply moved by the nobility of their vision for a free India. In different ways they both took heed of the message of the Mahatma’s message, working to reconcile competing points of views and alternative cultural or religious traditions. Particularly memorable was a handwritten letter of Nehru’s that I came across. It was dated 30 July 1947, and it read:

My dear Rajaji,

This is to remind you that you have to approach Shanmukham Chetty—this must be done soon.

I have seen Ambedkar and he has agreed…

Yours

Jawaharlal.

This brief note requires some explanation. R. K. Shanmukham Chetty was a businessman in the South widely admired as being one of the best financial minds in India. Ambedkar, the Dalit leader, was a brilliant legal scholar. But both had been lifelong enemies of the Congress. Now, a mere two weeks before the political freedom Rajaji and Nehru had spent years in prison for, they were approaching these old adversaries to join the first Cabinet of free India.

It was a gesture remarkable in its wisdom and in its generosity. In the event, but only after overcoming the hostility of the other Congressmen, Chetty became Finance Minister; Ambedkar, Minister for Law.

In 1950, Nehru hoped to be able to make Rajaji the first President of the Republic, but Patel and the Congress Old Guard thwarted him. Later in the year Rajaji joined the Cabinet, as Minister without Portfolio.

After Patel’s death in December 1950 he was asked to take over the crucial job of Home Minister. Not long afterwards, Rajaji left the Cabinet and returned to Madras. The ostensible reason was tiredness, but he seems also to have felt that he was not being consulted enough.

Anyway, his leaving Delhi was a tragedy, for Jawaharlal Nehru as well as for India. For, as Walter Crocker perceptively remarked in his study of Nehru, after the death of Patel the Prime Minister ‘needed the support of an equal. He needed, too, the criticism of an equal’. Now Rajaji was as close to Gandhi, had sacrificed as much in the freedom movement, and was a man of conspicuous integrity besides. He was indeed ‘the intellectual and moral equal of Nehru’. Had a way been found to retain Rajaji in Delhi, this would have, says Crocker, ‘ended the situation prevailing in which no one could, or would, stand up to the Prime Minister; the situation whereby he was surrounded by men all of whom owed to him their jobs, whether as Cabinet Ministers or as officials’.

In October 1951, after Rajaji had left Nehru’s Cabinet to return to Madras, the Prime Minister sounded him out on the job of Indian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and, when he refused, asked Lord Mountbatten to try and persuade him.

Mountbatten duly wrote to Rajaji, and in exchange got a blistering reply: ‘My career is truly remarkable in its zigzag…. Cabinet Minister, Governor without power, Governor General when the Constitution was to be wound up, Minister without Portfolio, Home Minister and… now the proposition is Acting High Commissioner in U. K.! Finally I must one day cheerfully accept a senior clerk’s place somewhere and raise that job to its proper and honoured importance’.

The job Rajaji did accept a few months later was that of Chief Minister of Madras. He stayed in that post until April 1954, when his party indicated that they wanted K. Kamaraj to replace him. Now Rajaji entered what neither his astrologer nor his own foresight had anticipated for him, namely, retirement from politics. He settled down in a small house to spend his days, he said, reading and writing.

But, in the end, philosophy and literature proved an inadequate substitute for public affairs. He was moved to comment from time to time on the nuclear arms race between Russia and America, with regard to which he took a line not dissimilar to that of Nehru. Then, when the Second Five Year Plan committed the Government of India to a socialist model of economics, he began commenting on domestic affairs too. Here, however, he came to be increasingly at odds with Nehru.

Consider now an article published by Rajaji in May 1958 under the title ‘Wanted: Independent Thinking’. This examined the ‘present discontent about the Congress’ from the perspective of one who ‘has spent the best part of his life-time serving the organization and who owes many honours and kindnesses to it’.

He worried that ‘as a result of tacit submission on the part of the people of emancipated India, a few good persons at the top, enjoying prestige and power, are acting like guardians of docile children rather than as leaders in a parliamentary democracy’.

‘The long reign of popular favourites, without any significant opposition’, wrote Rajaji, is ‘probably the main cause for the collapse of independent thinking’ in India. But a healthy democracy required ‘an Opposition that thinks differently and does not just want more of the same, a group of vigorously thinking citizens which aims at the general welfare, and not one that in order to get more votes from the so-called have-nots, offers more to them than the party in power has given, an Opposition that appeals to reason…’. Such an Opposition, even if it did not succeed in ousting the ruling party, might yet control and humanize it.

A year later, and touching eighty, Rajaji chose a public meeting in Bangalore to launch an all-out attack on the ‘megalomaniac’ economic and foreign policies of the Prime Minister. This was followed by the formation in Madras of a new political party, the Swatantra Party.

This party focused its criticisms on the ‘personality cult’ around the Prime Minister and on the economic policies of the ruling Congress. In a series of articles published in his journal Swarajya, Rajaji took apart these socialist pretensions. The Prime Minister’s ‘personal allergy’ towards private enterprise, he commented, was both unwarranted and unfair. For ‘it is as patriotic to start and manage a good private business concern, be it in industry or in transport or in distribution, as to be attached to a public managed industry either as an official or propagandist patron-saint’. But Nehru was moved instead by an admiration for Soviet Russia that was ‘taking different and various forms at national cost’.

Rajaji also sharply attacked the ‘megalomania that vitiates the present development policies’. What India needed, said he, ‘is not just big projects, but useful and fruitful projects… Big dams are good, but more essential are thousands of small projects which could be and would be executed by the enthusiasm of the local people because they directly and immediately improve their lives’. Speaking more generally, ‘the role of the Government should be that of a catalyst in stimulating economic development while individual initiative and enterprise are given fullest play’.

In September 1952, when Rajaji and Nehru were still friends, the American journalist and pioneering Gandhi biographer Louis Fischer wrote to him of his belief that ‘some straight talk to the power that is [Nehru], would do a lot of good, for I doubt whether time cures certain diseases…. You are the one man who… could appeal to his mind…’

At that time, of course, Rajaji was in the Congress; but now, seven years later, Nehru did not take well to these criticisms from a colleague-turned-adversary. Sometimes he affected a cavalier attitude—when asked at a press conference about his differences with Rajaji, he answered: ‘He likes the Old Testament. I like the New Testament’.

This was spoken in June 1959, but as the months went by the mood turned very sour indeed. In December 1961 Nehru told a group of newsmen that Rajaji ‘stands on a mountain peak by himself. Nobody understands him, nor does he understand anybody. We need not consider him in this connection. All his policies in regard to India, if I may say so, are bad—bad economics, bad sense, and bad temper’. Eighteen months later Nehru claimed that the party Rajaji had started, Swatantra, was ‘a mixture of the rottenest ideas imaginable’.

Sensitive observers mourned and worried about the gulf between the two. In May 1959, his biographer Monica Felton told Rajaji that ‘if I were the mother of you and the Prime Minister, I would bang your two heads together and tell you to stop arguing and to settle down and run things together’.

Walter Crocker thought their differences real, but by no means irreconcilable. Both loved freedom, both were deeply moral beings, and both were passionately committed to social and religious tolerance. Yet they fell out. ‘Here was great drama’, writes Crocker: ‘Two figures of Shakespearean scale in contest. And the drama was tragedy, for the contest was needless. Both men were required by India in the two crucial decades following Independence; and both men shared the blame, though perhaps not in equal measure, that there had been fission, not fusion, between them’.

The assessment of Nehru’s own sister, Vijayalakshmi Pandit, was not dissimilar to this. As she wrote to Rajaji in June 1964: ‘It seemed such a bad thing that two men like yourself and Bhai who had contributed so much individually and jointly to our beloved India should be apart at a time of national crisis. But the moment passed and now it is too late’.

This was written weeks after the death of Nehru. That event had occasioned a brief obituary published by Rajaji in Swarajya:

Eleven years younger than me, eleven times more important to the nation, eleven hundred times more beloved of the nation, Sri Nehru has suddenly departed from our midst and I remain alive to hear the sad news from Delhi—and bear the shock….

The old guard-room is completely empty now… I have been fighting Sri Nehru all these ten years over what I consider faults in public policies. But I knew all along that he alone could get them corrected. No one else would dare do it, and he is gone, leaving me weaker than before in my fight. But fighting apart, a beloved friend is gone, the most civilized person among us all. Not many among us are civilized yet.

God save our people.

These words might serve as an epitaph to the relationship between these two remarkable men. Or one might choose instead the story of Edwina Mountbatten’s visit to Madras in early 1953. Told about the visit, Rajaji drew up a punishing programme, where Lady Mountbatten would have to visit Corporation slums, meet social workers, open a high school, have tea with Army wives, see the temples at Mahabalipuram and dine at the Raj Bhavan.

When this schedule was sent back to Delhi, it provoked this panic-striken telegram from the Prime Minister: ‘Programme sent by Mary Clubwalla for Edwina’s visit to Madras is rather heavy. She has not been very fit. There is no mention in programme of her visit to you. This is main purpose of her going to Madras’.

This, read intelligently, might even be the most generous compliment ever paid by Nehru to a fellow Indian. If Edwina is to have stimulating conversation in India, he is saying to Rajaji, and if it is to be with someone other than myself, then it must only be with you.

RAJAJI AND THE BOMB

Mahatma Gandhi once remarked that the atom bomb was ‘the greatest sin known to science’. After India exploded a nuclear device in May 1998, and the nation swirled around itself in hysteria, it took a contemporary Gandhian to remember what the master had said.

Thus, the first dissenting article in the national press was written by the veteran architect Laurie Baker, who recalled the three tests an invention of science had to pass in a country such as ours. These were: Is it non-violent? Is it eco-friendly? Is it poverty-reducing? The answers, in the case at hand, were No, No, and No.

India is now a certifiable nuclear power. This would have displeased Gandhi, and also displeased C. Rajagopalachari, the Gandhian who, in his lifetime, mounted the most sustained campaign against nuclear weapons. In 1945, after the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he quipped: ‘All this while we knew only of the chemist’s bombs. Now we know of bombs made by physicists.’

A decade later his tone was deadly serious. Rajmohan Gandhi quotes from a letter written by Rajaji to the New York Times at the end of 1954, in which he urged each party in the Cold War not to ‘wait for the other’, but to unilaterally ‘throw all the atomic bombs in the deep Antarctic and begin a new world free from fear’.

In 1959, in a piece directed against nuclear tests, Rajaji wrote in disgust of ‘politicians and technicians who do not believe in co-existence and mutual trust, but are convinced, and have been doing their best to educate the people to believe, that the best defence of national existence is to make it clear that they have terrible weapons of retaliation.

And this is naturally associated with a policy of armament manufacture to achieve that retaliatory strength and purpose’. He was speaking, of course, of America and Russia, then, but he could as well have been speaking of India and Pakistan, now.

Rajaji thought the making of atom bombs was the product of hubris, with man now believing he ‘had the rights and privileges of the sun or even of the Lord God himself.’ It was, he remarked, ‘an unfortunate day when science lifted the curtain of fundamental matter and trespassed into the greenroom of creation’.

Rajaji made a distinction between a ‘free science’ which honestly documented the radiation effects of nuclear tests, and a ‘hired science’ which tried to doctor its results. These tests, he said, were ‘a wholly illegitimate attack on the health of the present and future generations of the uninvolved millions, who have not yet written off their rights in favour of the nuclear pugilists’.

Rajaji’s campaign against nuclear arms culminated in a journey he made to the United Kingdom and the United States in 1962, at the head of a three member delegation travelling under the auspices of the Gandhi Peace Foundation. (The other members were R. R. Diwakar and B. Shiva Rao.)

Rajaji was already eighty-three, and this, believe it or not, was his first trip to the West. In America he met with, among others, Henry Kissinger; Robert Oppenheimer (the man who had led the Los Alamos team that made the atom bomb, but had later thrown his hat into the peace camp); and the Representatives to the United Nations of Soviet Union and the United States. Rajaji also spoke at several universities and at the prestigious Council for Foreign Relations in New York. All through, he pursued his case against the Bomb with (to quote his biographer, Rajmohan Gandhi) ‘the energy of a 40-year-old’.

The highlight of the trip was a meeting with John F. Kennedy, who gave the delegation twenty-five minutes, but was so charmed by Rajaji that in the end they chatted for over an hour. Later, Kennedy told an aide that ‘seldom have I heard a case presented with such precision, clarity and elegance of language’. He added that the interview had ‘a civilizing quality about it’.

The diplomat B. K. Nehru, who was present, later recalled how ‘the secretaries who came in with slips of paper reminding the President of his appointments were shooed away’. Kennedy, it appears, was ‘fascinated’ by Rajaji’.

But Rajaji wasn’t entirely sure that the President was convinced. A week later, the journalist Vincent Shean met him in New York, and sought to gift him a stamp of Mahatma Gandhi just issued by the U. S. Postal Department. ‘You keep it’, said Rajaji to Shean, ‘and use it in a letter to Kennedy asking for the renunciation of the atomic bomb’.

After the delegation’s return to India, B. Shiva Rao wrote to Jawaharlal Nehru of the impact its leader had made. When Rajaji spoke at the Council of Foreign Relations, the leader of the American delegation to the U. N. Disarmament Conference in Geneva told Shiva Rao: ‘Why don’t you send this man to represent India at Geneva?’

Altogether, Rajaji had made ‘a deep impression on all the persons he saw in the U. S. A. and England’. He would, Shiva Rao told the Prime Minister, ‘make an admirable representative for India… in Geneva’. He was ‘extremely able and dignified in his presentation of the case for nuclear disarmament’. Were he indeed to be sent as the Government’s representative to the talks, it would aid India in playing ‘a constructive part in bringing about phased disarmament…’

The suggestion was well meant, and well merited. But by this time Nehru and Rajaji were in rival political parties. True, they agreed on the Bomb, but the older man’s attacks on his economic and social policies the Prime Minister found hard to forgive. ‘Rajaji is undoubtedly a person of high ability’, replied Nehru to Shiva Rao, ‘and we all have respect and affection for him. But I doubt very much if he will at all suit or fit in with the Disarmament Conference at Geneva which consists of senior officials. Also, unfortunately, he disagrees with almost everything in the domestic or international sphere for which some of us stand’. Partisan considerations would not allow India to send its best man to Geneva.

Strikingly, Rajaji was against atomic power as well as atomic weapons. When, in 1954, the Times of India insisted that nuclear energy was vital to a ‘power-starved’ India, Rajaji drew their attention to the ‘terrible character of the risks necessarily attached’ to this industry.

Its process of production ‘totally disregards the rights of those that do not in any way benefit from the enterprises’. Moreover, ‘the general public is almost entirely ignorant of all that the new power source involves. It is not like coal or oil but comparable to a hypothetical case of using the thunderbolt to cook our breakfast’.

This was characteristically acute, as well as prescient, for it took another two or three decades before science, and society, made a proper acquaintance with the risks and costs of nuclear power.

The anti-nuclear movement in India has witnessed the not always comfortable co-existence of Gandhians and Communists. However, after 1998, it has been more-or-less captured by the Left who, on the one hand, do not question the dangers of nuclear energy and, on the other, seem to think that nuclear weapons are somehow safe if placed in the hands of Red regimes.

Rajaji’s work has a more general relevance to questions of scientific ethics and nationalist military rivalry, but it also has a more specific relevance, to the ethics of the anti-nuclear movement. He once expressed his wish to ‘rescue the peace movement from the clutches of the Communist Party’. It is a task that remains unfinished.

(Series concluded)

This essay first appeared in Ramachandra Guha’s book ‘The Last Liberal and Other Essays’ (2004). It is being reprinted with the permission of the author.