Ayn Rand vs. Aristotle – Self Love, Selfishness, and Egoism

The phenomenon of friendship, with its richness and complexity, its ability to support but also at times to undercut virtue, and the promise it holds out of bringing together in one happy union so much of what is highest and so much of what is sweetest in life, formed a fruitful topic of philosophic inquiry for the ancients writes Lorraine Pangle in her introduction to Aristotle and the Philosophy of Friendship. The fullest and most probing classical study of friendship is to be found in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, which devotes more space to it than to any of the moral virtues, and which presents friendship as a bridge between the moral virtues, and the highest life of philosophy. Pangle contends that it is precisely in the friendships of mature and virtuous individuals that Aristotle saw human love not only at its most revealing, but also at its richest and highest.

Philosophy since Kant has largely followed him in understanding truly moral, praiseworthy human relations to be based on altruism, a wholly selfless benevolence towards others, guided either by absolute moral law or by a utilitarian pursuit of the greatest good for the greatest number. When compared to friendship, altruism directed to the good of humanity seems higher, more selfless, more rational, and more fair Today we reasonably assume that the enemy of morality is selfishness. Starting from self-interest, we would find acquisition, pleasure, and selfishness the primary threats to, and alternatives to, virtue. But is altruism really possible? How are our altruistic motives, related to our self-interested motives? If we normally act with a view to our own good, but sometimes choose actions that have nothing to do with our own good, or even oppose it — is there any higher, unifying principle or faculty of the soul that decides between these contrary principles of action, judging them by a common standard?

Ayn Rand rejected altruism, and in fact, blamed it for the plight of human civilization, and with the presumed backing of Aristotle, wrote fervently in support of self-interest and rational egoism in The Fountainhead, Atlas Shrugged, and in her other writings. Aristotle assumes neither the possibility nor the impossibility of what we would call altruism, but instead offers a sustained and sympathetic exploration of what is really at work in the human heart when an individual seems to disregard his own good to pursue the good of others. Aristotle does not assume that the concern for a friend is necessarily tainted by partiality; he argues that friendship can be rooted in a true assessment of the friends’ worth and as such can be the noblest expression of human relationship. He nonetheless insisted that self-love was the highest love and maintained a conception of selfishness, such that it not only contributed to, but was requisite for, virtuous living. This particular understanding of selfishness is best explained in his chapters on friendship in the Nicomachean Ethics, but it is also referred to in numerous other writings, such that there can be no doubt that he sincerely held this belief. Ayn Rand holds Aristotle in the highest regard and utilizes his conception of selfishness as the philosophical underpinning for her version of egoism and objectivism. While I agree that there are certain Aristotelian ideas of selfishness which might lend support to some aspects of her theory, for the most part, she has taken Aristotle out of context or has been represented to have done so by authors elaborating upon Rand’s ideas. My primary objective here, then, is to refute Rand’s claim of Aristotelian support for her beliefs and demonstrate how and where her interpretation went astray through a careful analysis of Aristotle’s conception of virtue and friendship

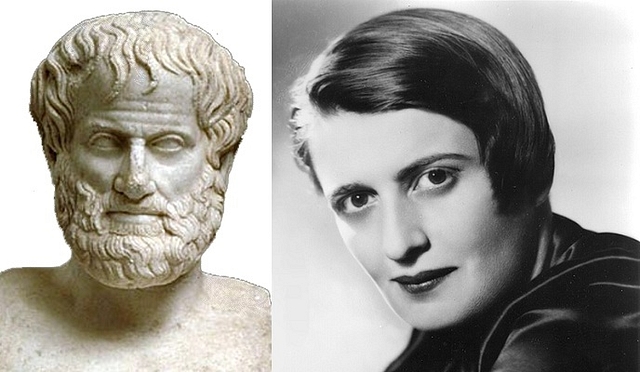

Aristotle

Central to Aristotle’s ethics is his concept of living well (eudaimonia), which he describes as living in accordance with the virtues. He places friendship as one of the virtues necessary for living well, an essential ingredient for attaining the virtuous life. Aristotle says, “A discussion of friendship would naturally follow, since it is a virtue or implies virtue, and is besides most necessary with a view of living”. “For without friends no one would choose to live, though he had all other goods” (1155a). In fact, Aristotle sees friendship as an essential aspect of a life of happiness and morality, “the friendship of good men is good, being augmented by their companionship; and they are thought to become better by their activities and by improving each other; for from each other they take the mold of the characteristics they approve” (1172a). Friendship seems to have an especially close connection with moral virtue, standing as a crucial link in a chain that the treatment of the separate virtues has not yet completed. In the lives of virtuous agents, friendship is far more involved and significant than just good will, actually aiding their progression towards fulfilling their ultimate end goal, which for Aristotle is human flourishing. Aristotle is committed to the unity of virtue and happiness and rejects the commonly held notion that what is really good for us is not what is most pleasant, and that what is right or noble is often neither good nor pleasant. Aristotle argues, to the contrary, that the activity of virtue is the very substance of human happiness and this unity for Aristotle seems best achieved within the context of serious friendship.

Aristotle also bases his political theory on friendship. Amity among people in the society is requisite for the proper function of the social order, which for him, of course, was the Athenian polis. Eugene Garver, in Confronting Aristotle’s Ethics, points out that “the task of the Politics is to show how nature and habit can produce citizens who care about the good life. The task of the Ethics is to show how our rational powers and our thumos can be fulfilled through virtuous activity.” A love of honour propels people into activities that are their own end rather than directed at given ends. Since, for Aristotle, activity is the ultimate expression of virtue, action motivated in this way serves, in addition to its external end, as an end in itself, furthering the individual’s habituation of virtuous decision-making. “Aristotle must show how the thumos will be fulfilled in doing virtuous actions for their own sake, not through theory alone, as Socrates argues, and not, as many of his students must have thought, through political ambition for domination. The Nicomachean Ethics is that demonstration.”

Alastair McIntyre writes in After Virtue that the type of friendship which Aristotle has in mind is that, which embodies a shared recognition of, and pursuit of, a good. It is this sharing which is essential and primary to the constitution of any form of community, whether that of a household or that of the city.

Lawgivers, says Aristotle, seem to make friendships a more important aim than justice (1155a24); and the reason is clear. Justice is the virtue of rewarding desert and of repairing failures in rewarding desert within an already constituted community; friendship is required for that initial constitution… Friendship on Aristotle’s view involves affection. But that affection arises within a relationship defined in terms of a common allegiance to and the common pursuit of goods. The affection is secondary, which is not in the least to say, unimportant. This contrasts with our modern perspective in which affection is often the central issue. Friendship has become for the most part the name of a type of emotional state, rather than that of a type of social and political relationship. Indeed, from an Aristotelian point of view, a modern liberal political society can appear only as a collection of unconnected men who have banded together for their common protection. That they lack the bond of friendship is of course bound up with the self avowed moral pluralism of such liberal societies.

One can clearly see from the aforementioned discussion that Aristotle’s ethics are rooted in a social context, in which the virtuous man participates with the other citizens to ensure a just and amicable social order. What a stark contrast to Ayn Rand’s character John Galt who, in Atlas Shrugged, rejects any obligation to his fellow man in a lengthy 60-page speech in which Rand introduced her view of egoism and her brand of philosophy which she called objectivism. Rand cannot cite Aristotle in support of her ethical prescription — “do what maximizes your self-interest”, or her assertion that “man must exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself.” Aristotle’s emphasis on virtue and upon man’s attainment of the highest goal in life through virtuous action revolves around living in friendship and community with others, as a social creature.

Aristotle’s view of the world is teleological, and man’s telos is firstly that of rational animal, and secondly, and almost as importantly, that of social animal. This is the case for man, because in order to live a life of flourishing, which for Aristotle is man’s purpose, one requires the company of others with whom one stands in relation, such that, “by doing what is noble he will at once benefit himself and others.” Aristotle has also said that a friend is another self, and I see myself in him. Simply by interacting with others, one’s values when shared with another are revealed, thus providing a concrete experience of those traits valued abstractly by the individual. “Furthermore, it is quite true to say of the good man that he does many things for the sake of his friends, and his country and will even die for them if need be. He will throw away money, honor, and in a word all good things for which men compete, claiming the noble for himself.”

The contrast between these quotes of Aristotle and Rand seem to draw a distinction between Aristotle’s virtue ethics and Rand’s rational egoism. Much recent discussion in ethics has amassed around the edges of egoism, as renewed attention to virtue ethics, eudaimonia, and perfectionism naturally raises questions about the role of self-interest in a good life, notes Tara Smith in the introduction to Ayn Rand’s Normative Ethics (Cambridge, 2006). She quotes Rosalind Hursthouse from her book, On Virtue Ethics (Oxford 1999), “much virtue ethics portrays morality as a form of enlightened self-interest.” Although the Aristotelian conception of ethics that is currently enjoying a revival does not fit stereotypes of egoism, admits Smith, she claims that it certainly does not advocate altruism. Smith has written an elegant and thorough text of Rand’s ethics in which she gives it a more robust and developed philosophical footing than Rand did herself. In fact, between Smith, Leonard Peikoff, and Fred Seddon, Rand’s ethics have become far more palatable and far less polemical. It is Smith who has borrowed heavily from Aristotle in fleshing out the ethics attributed to Rand. She asks a number of provocative questions, which I too would like to address: “ Is eudemonia a selfish end? What does selfishness actually mean? What sorts of actions does it demand? What are the implications of pursuing eudaimonia for a person’s relationships with others?” Aristotle has answered these questions in his ethical writing, particularly in the Nichomachean Ethics.

It is worth delving into Aristotle’s concept of character friendships, which are those friendships of the highest order and those in which selfishness plays a significant role, while concomitantly developing the egoism of Rand, distinguishing the similarities and differences between the two philosophers and addressing the questions raised above. Aristotle has crafted an ingenious theory, which results in the synthesis of selfishness and altruism. Aristotle’s idea of thumos is also quite important for us to better understand what he means by selfishness.

Friendship holds a very important position in Aristotle’s ethics, for his ethics are practical and are based upon the human goals and interrelationships commonly encountered in everyday life. The centrality of friendship extends beyond the personal life of the individual and even household relations to serve as the crux of political and societal flourishing and success. Aristotle’s definition of friendship, broadly speaking, is a practical and emotional relationship of mutual and equal goodwill, affection, and pleasure. Through an analysis of end love in friendship, distinguishing it from means love, we can begin to unpack Aristotle’s notion of self-love and its primacy. For Aristotle, the highest most complete form of friendship is referred to as character friendship and is distinct in that friends love and wish each other well as ends in themselves, not solely or even primarily as a means to further ends. Friendship consists in loving and being loved (1381a1-2), but more in loving (1159a33-34). Aristotle claims that friendship is, in fact, necessary if we are to attain a life of flourishing. Initially, he explains this in the Magna Moralia, asserting that character friendship is necessary for self-knowledge and is essential for avoidance of self-delusion and false assessment of one’s own virtuousness. We need the objectivity of a friend to see what we cannot, or often do not, see in ourselves. Aristotle clearly is emphasizing our human vulnerability and weakness, for it is in the propensity to uncertainty and doubt about oneself that the need for such a friendship becomes clear. Aristotle is here acknowledging deficiencies in the psychological makeup of human nature, such that the individual, in isolation, is insufficient to achieve a life of virtue and happiness.

In this type of friendship, we care for our friends’ material health, spiritual health and state well-being as an end in itself and as an expression of our love. This level of caring concern has often been described as altruistic and cannot be achieved unless we distinctly recognize and love the moral goodness in the friend, viewing his life as worthwhile in the same way as our own. Aristotle feels that only in this way, and through such relationships, does one become able to love and value himself.

When asked whether it is right that a man love himself more than he loves others, Aristotle responds in the affirmative. He asserts that the prevailing theory that a good man, out of regard for his friend, neglects his own self-interest, disagrees with the facts, as well it should. He states that we would all agree that we should love him most who is most truly a friend and should wish him well for his own sake. All these characteristics that go to define a friend are found to the highest degree in oneself, and it is from our relationship with ourselves that our friendly relations are derived and man is his own best friend. A man must therefore love himself better than anyone else. The term self loving can be used as a criticism if a man takes more than his fair share of money, honor, and bodily pleasures for in this case he indulges his animal appetites and the irrational part of his nature. This, unfortunately, he says, applies to the mass of men. The man, who set himself on the course of justice and virtue, temperate, moderate, and noble, would not be called self loving by others, yet he is even more self loving for he takes for himself what is noblest and most truly good. For Aristotle, our reason and our rational self is most truly ourself and, when a man acts under the guidance of his reason, he is thought in the fullest sense to have done the deed himself and of his own free will. The good man, then, ought to be self loving, pursuing the virtuous and noble. The needs of the community would be perfectly satisfied, and simultaneously each individual would achieve virtue, which is the greatest of all good things. Such a man will surrender wealth to enrich a friend; for while his friend gets money, the man gets what is noble and thus takes the greater good for himself. Similarly, this holds with regard to honors and offices. (1168a29-1169)

For a character friend to be able to positively influence our growth requires that he have a deep knowledge and understanding of our true nature as well as the trust and connectedness necessary to be able to honestly criticize us. For Aristotle, self-assessment is a key ingredient in attainment of virtue and its habituation. He envisions this friendship as one in which much time is spent together both pursuing mutually enjoyable activities and in contemplation and conversation. This type of friendship obviously requires considerable time to develop and may have begun as a friendship of utility or amusement, growing into a deeper, mutual, commitment as the nature and depth of each character is revealed. Such a friendship is a lasting friendship and is based in part upon each individual’s integrity and in part upon mutual trust.

Garver notes that thumos is the source of ambition, aggression, love, and personal identity for Aristotle. People must be both intelligent (dianoetikous) and spirited (thumoeideis) if they are to be led easily toward virtue.

Thumos is the faculty of our souls, which issues in love and friendship. An indication of this is that thumos is more aroused against intimates and friends than against unknown persons. When it considers itself slighted…. both the element of ruling and the element of freedom, stem from this capacity for every one. (1327b40-1328a7)

In his chapter entitled “Passion and the Two Sides of Virtue”, Garver asks the question what is thumos, and how does it lead to such things? “I leave thumos untranslated, because spirit, ambition, anger and assertiveness all seem partially right, but more importantly, I need to leave open its status, possibly, as simply a posit. Maybe we refer affectionateness, the power to command, and the love of freedom to thumos, because we can’t explain them.” In a footnote, Garver writes that in Christian moral psychology, to oversimplify, thumos is replaced by the will as the supplement to reason and passion. In modern moral psychology, ‘thumos’ is replaced as the supplement to reason and passion by self-interest. It is the ‘thumos’ that renders the classical Aristotelian theory of friendship explicitly self- centered. The thumos, i.e. the prideful, self-vindicating and self-policing faculty or part of the soul, the part in which the sense of self most resides, also happens to be the part that creates affection.

Thumos then seems to provide an answer to why people generate personal ends and love the noble for its own sake. It is through this conception of ‘thumos’ that, for Aristotle, affection is seen as an extension of the self to encompass concern for another or for others. Aristotle’s ethical theory then addresses the contemporary egoist/altruist dilemma, implicitly, by denying that it exists. ‘Thumos’ does have a downside in Aristotle’s usage, and it is perhaps the interpretation of ‘thumos’ as “drive” which captures Aristotle’s concern that thumos, in the absence of virtue, may lead to the desire to rule despotically and live tyrannically. “Yet only ambition, and spiritedness (thumos), can push people from life into good life.” Without ambition, people would not have the ethical problems that the ethical virtues are designed to overcome. Coupled with this drive then, must be reason (logos), such that thumos then both allows us to love, and to engage in actions that are their own end (Garver, pg.120). Explaining why people should want to do things for their own sake is equivalent to explaining why good people should love and not just want to be loved.

All people or the majority of them wish noble things, but choose beneficial ones; and treating someone well, not in order to be repaid, is noble, but being the recipient of a good service is beneficial.” (1162b34-1163a1). “It is rather the part of virtue to act well than to be acted upon well. (1120a1112)

Rooting friendship in thumos has advantages over modern discussions of altruism. We today take selfishness as a given and then try to explain altruistic behavior. For Aristotle all friendship (philia) is rooted in self-love (philautia). The right kind of self-love is an achievement, love for what is best in us, motivated by self-love. Aristotelian friendship is unlike altruism in that there is no sacrifice of the self to others. Friendship and the desire for the noble then, are the good development of the thumos. Love for the noble, is senseless under the wrong conditions. Only in the right community, which for Aristotle is the polis, in which virtue is praised and vice punished and in which one’s natural ambition can be satisfied in activities within that community, can one reasonably choose to engage in activity for its own sake and thus pursue the noble. This sheds some light upon why the ideas of Aristotle were not readily adaptable to the tumultuous world of Ayn Rand.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle provides a comprehensive course on the meaning and significance of friendship. He addresses the possibility of altruism and egoism in the context of friendship, concluding that, “the prevailing theory is that a good man, out of regard for his friends, neglects his own self interest. However, the facts are not in harmony of these arguments, and that is not surprising (1168a29). In defense of this rather egoistic assertion, Aristotle posits the following argument:

it is said that we should love our best friend, and the best friend, is he who when he wishes for someone’s good does so for that person’s sake even if no one will ever know. Now a man has this sentiment, primarily toward himself, and the same is true of all the other sentiments of which a friend is defined. For as we have stated, all friendly feelings toward others are an extension of the friendly feelings a person has for himself. All these sentiments will be found chiefly in a man’s relation to himself, since a man is his own best friend, and therefore should have the greatest affection for himself. (1168b)

Aristotle goes on to clarify that the term self loving can be used as a criticism if a man takes more than his fair share of money, honor or bodily pleasures, for in this way he indulges his animal appetites and the irrational part of his nature:

Hence, the pejorative use of the term is derived from the fact that the most common form of self love is base, and those who are egoists in this sense are justly criticized.” “If a man were always to devote his attention above all else to acting justly himself, to acting with self-control, or to fulfilling whatever other demands virtue makes upon him, and if in general, he were always to try to secure for himself what is noble, no one would call him an egoist and no one would find fault with him. He assigns what is supremely noble and good to himself, he gratifies the most sovereign part of himself, and he obeys it in everything. Consequently, he is an egoist or self lover in the truest sense, who loves and gratifies the most sovereign element in him.” “His self love is different in kind from that of the egoist with whom people find fault: as different, in fact, as living by the guidance of reason is from living by the dictates of the emotion, and as different as desiring what is noble, is from desiring what seems to be advantageous. If all men were to compete for what is noble, and put all their efforts into the performance of the noblest actions, all the needs of the community will have been met, and each individual will have the greatest of goods, since that is what virtue is. Therefore a good man, should be a self lover, for he will profit, by performing noble actions, and will benefit his fellow man. It is also true that many actions of a man of high moral standards are performed in the interest of his friends and of his country, and if there be need, he will give his life for them. He will freely give his money, honors, in short, all the things that men compete for, while he gains the nobility for himself…. So we see that in everything praiseworthy a man of high moral standards assigns himself a larger share of what is noble. It is in this sense, then, as we said, that he ought to be an egoist or self lover, but he must not be an egoist in the sense in which most people are. (1168b20-33)

Selfishness for Aristotle does not hold negative connotation, when considered in the context of a good or virtuous man., but rather motivates human action. The development of rational goodness, through virtuous living, serves to produce alignment of his self interest with that of the community, such that his actions inure to the benefit of family, friends, and society. Aristotle is very clear when discussing selfishness in the context of character friendship to point out that it is only the good and virtuous, which are capable of having such character friendships and are thus capable of being selfish. This is the only way in which selfishness is appropriate and desirable for Aristotle. He quickly points out that those who are not good cannot have friendships of the highest type, and for them selfishness is most unacceptable.

When reading Aristotle’s chapters on friendship, if one were to cherry pick certain passages, one could easily fabricate an endorsement of egoism. In context, however, Aristotle is speaking selectively to men of the Athenian polis, and even more selectively to those citizens who are already leading a reasonably virtuous life. Even more selectively, because most of his writings indeed were lecture notes, Aristotle is speaking to the sons of the citizens of Athens, with instructions for their future lives as productive citizens of the polis. When we read the entirety of his treatment of friendship, we note that included in this context is the relationship of parent and child and the relationships within the household. I interpret Aristotle’s teaching regarding character friendship and self-love to be a prescription for developing and maintaining relationships in adulthood, which will continue to provide a similar form of feedback to that which one receives in childhood and adolescence from one’s parents and teachers.

It is not hard to see how a character friendship would be immeasurably beneficial in the attainment of, and furthering of, self-knowledge and virtue for those already aiming for a life of virtuous living. The modeling of virtuous behavior readily observable in our friend surely contributes to our ability to assimilate and habituate virtuous behaviors of our own. A study of Aristotle’s conception of virtue qua virtue, and of happiness, which derives from it, would be helpful at this point to understand more fully the interconnectedness of friendship and the virtuous life.

Aristotle identified two virtues of thought, otherwise known as moral virtues. The first is practical wisdom and is the virtue of the practical intellect truly inseparable from virtues of character. The second, which he calls philosophy, is the virtue of the speculative intellect. Practical wisdom enunciates the rules which virtues of character carry out. Particularly, if we wish to comprehend how Aristotle comes to the conclusion that friendship is indispensable for human happiness and flourishing we must understand how these two activities of the mind (soul) function as co-chairs, presiding over all other activities of the human being.

Practical wisdom exercises command and thus rules over desire, that is, over the body and its animalistic appetitive characteristics. Similarly philosophy, as the activity of contemplation has its own realm, namely that of spectator of itself. This function is regulative of action in a sense, issuing orders, and also serves to inform us about ourselves, but is not the initiator of any action. Parenthetically, one can readily see that this concept of reason was adopted by Kant. Practical wisdom perfects not only the subject and its desire by teaching it to obey well, but also perfects the mind teaching it to command well.

Virtues are for Aristotle, dispositions, and are developed through habituation. Virtue of character is a state of habit through which we are disposed toward the highest virtues in a certain way to a certain set of stimuli or situations. Virtue as habit is not innate, though certainly there is a predisposition to virtue in our human nature. Virtue has two aspects, an objective experiential one and a subjective or mental one. Actions for Aristotle are not virtuous (though they may have the appearance of virtuosity to the observer), unless they concomitantly emanate from a certain state of mind. This has alternatively been stated such that virtuous action requires right action for the right reasons in the right situation. Neither “good intentions” nor accidental good acts qualify as virtuous.

A more precise understanding of virtue should become evident as we look at its development in the life of the human subject, which is precisely where friendship comes into play for Aristotle. From the earliest points of development, the social and interactive nature of the human species is no more evident in Aristotle’s biology than in our learning, and particularly our learning to manifest our “predispositions” as “dispositions”, resulting in “right” or “virtuous” action. The very apparent mimicking and mirroring of the actions and attitudes of their parents by young children does not end in childhood from Aristotle’s point of view, but persists throughout life.

It is for this reason, that in his discussion of friendship he includes the relationship and philia of parents for children, and children for parents, in the category of friendship. Understanding the primary role of friendship is essential and necessary for attainment of the virtues, which then can be properly utilized toward the attainment of a life of flourishing.

The benchmark for assessing the virtuousness of an action is referred to as the mean, however Aristotle does not envision a quantitative mean, such as described by Plato and other pre-Socratics. For Aristotle, the mean simply represents the moral ought without a quantitative component, because virtue for Aristotle was situated between two vices but not necessarily equidistantly. “The mean is to do what one ought, when one ought, in the circumstances in which one ought, to the people to whom, which one ought, for the end for which one ought, in the way, that one ought.” Thus the “mean” is duty (1121b12), and “ought” is what the moral rule prescribes. The mean is to act as the “right rule” says, but what is the right rule for Aristotle? He certainly did not have in mind any underlying determinant measure such as Kant’s categorical imperative.

For Aristotle, the standard is the ideal of the “virtuous man” (1113a33; 1176a15-17). The virtuous man is also a wise man (1107a1-2) from whom practical wisdom generates the rule as specific for a given situation (1144b27-28).

All the virtues have as their object, interior passions and simultaneously exterior actions or activities, and they moderate certain passions in order to moderate certain activities. Aristotle however is not prone to overtly rely on this “golden mean” as the solution to all moral dilemmas, or as the basis for all “right action”. He is much more inclined to allow the “virtuous man”, properly prepared through the learned behaviors and attitudes acquired through social contact from childhood to the present, and through contemplative reflection, to properly and correctly interpret that which is at hand, and to choose that action, which is responsively indicated. One can see from this that we have formulated a description of what has come to be known as “Virtue Ethics”. Aristotle now has connected the necessity of friendship in achieving this virtuous living and a life of flourishing.

Ayn Rand

Tara Smith is clearly a proponent of Rand’s rational egoism, elucidating and defending it in her book. Rand did not write her moral philosophy in lengthy treatises. Rather her views were presented in her fiction, particularly in the speech by John Galt near the end of Atlas Shrugged, and in her single most important essay “The Objectivist Ethics”. In addition to The Fountainhead, and Atlas Shrugged, we should also look at two collections of her essays titled, The Virtue of Selfishness (Signet 1964) and The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought (Signet 1988) for a fuller understanding. Rand’s ethics can be summarised by directly quoting from her essay, “The Objectivist Ethics”:

The objectivist ethics, proudly advocates and upholds rational selfishness –which means: the values required for man’s survival qua man — which means: the values required for human survival. The Objectivist ethics holds that human good does not require human sacrifices and cannot be achieved by the sacrifice of anyone to anyone yet holds that the rational interests of men do not clash—that there is no conflict of interests among men who do not desire the unearned, who do not make sacrifices nor accept them, who deal with one another as traders, getting value for value. The principle of trade is the only rational ethical principle for all human relationships, personal and social, private and public, spiritual and material. Each trader is a man who earns what he gets and does not give or take the undeserved. He deals with man, by means of a free, voluntary, unforced, uncoerced exchange—an exchange which benefits both parties by their own independent judgment.

Love, friendship, respect and admiration are the emotional response of one man to the virtues of another, the spiritual payment given in exchange for the personal, selfish pleasure which one man derives from the virtues of another man’s character.

To love is to value. Only a rationally selfish man, a man of self – esteem, is capable of love—because he is the only man capable of holding firm, consistent, uncompromising, unbetrayed values. It is only on the basis of rational selfishness that man can be fit to live together in a free, peaceful, prosperous, benevolent, rational society.

The only proper, moral purpose of a government is to protect man’s rights, which means to protect them from physical violence. Today the world is facing a choice: if civilization is to survive, it is the altruist morality that men have to reject.

Aristotle would clearly stand in opposition to the conception of trader or to the belief that a man should neither give nor get the undeserved. Aristotle explicitly states that if the friendship is between unequals and the help or benefaction is mostly one way, that is, if one party is always giving and the other always receiving, then the giver’s affection grows as he invests both materially and emotionally in the other. The recipient must obviously do nothing to damage that bond, but benefactors can even come to care about recipients, ignorant of the source of their good fortune. In the end, the recipient becomes a part of the giver, partially a product of his activity and life. By way of example, if I have gone to the expense of helping to put someone through college, their successes after college give me more joy than if I had done nothing to help them.

Turning now to Rand’s philosophy of love and friendship, I will quote from her essay, “The Ethics of Emergencies”:

Love and friendship are profoundly personal, selfish values: love is an expression and assertion of self-esteem, a response to one’s own values in the person of another. One gains a profoundly personal, selfish joy from the mere existence of the person one loves. It is one’s own personal, selfish happiness that one seeks, earns and derives from love. Concern for the welfare of those one loves is the rational part of one’s selfish interests.

The proper method of judging when or whether one should help another person is by reference to one’s own rational self-interest. If it is the man or woman one loves, that one can be willing to give one’s own life to save him or her—for the selfish reason that life without the loved person would be unbearable.

The same principle applies to relationships among friends. If one’s friend is in trouble, one should act to help them by what ever non-sacrificial means are appropriate. But this is a reward, which men have to earn by means of their virtues. If he finds them to be virtuous, he grants them personal, individual value and appreciation, in proportion to their virtues.

Rand again seems to stumble over her conception of affection and love because of a false dichotomy which she has drawn with utility. Her need for the constant reassessment of the mutuality of benefit from the relationship, robs it of its spontaneity and its humanity.

I thought it most appropriate to quote Rand’s essay’s directly, and in context, thereby obviating the possibility of being subject to the complaints voiced by a number of her proponents. Those sympathetic to her philosophy, such as Fred Seddon who wrote Ayn Rand, Objectivists, and the History of Philosophy, and Tara Smith complain about how severely misunderstood and misinterpreted her writings have been. Regardless of their level of sympathy for Rand, they agree that she works from the premise that life does not require sacrifice. She is an egoist, and she preaches an ethic of rational self-interest. For her, the primary virtue is rationality, the ultimate value is life and the primary beneficiary is oneself. Both Seddon and Smith argue that when she speaks of ‘life’ as the standard of value, she means a flourishing life, Smith even using the Aristotelian word eudaimonia.

Throughout her writings, notably those cited above, Rand uses verbiage not dissimilar to that of Aristotle. There are significant differences however, in addition to the tone of her voice, which in itself is more contentious and abrasive. Rand wishes to hold friendship entirely hostage to self-interest and egoism, reducing it to the relationship between traders. Aristotle clearly describes this type of friendship in the Nicomachean Ethics as a friendship of utility, which is not at all that which he refers to as character friendship. Each reference to feelings or emotions and relationships of friendship or of love, for Rand is immediately couched in self-interest and selfishness. One can’t help but interpret her as viewing all those with whom one may potentially be in relationship as objects, and as clearly other. Aristotle has attempted to describe the connectedness in the highest relationships as extensions of ourselves. Our friend becomes another self whom we love, nurture, and protect as we do ourselves. It is only in this way, that Aristotle justifies selfishness; interpreting the growth in virtue and nobility that we attain while giving freely of ourselves to our friends as taking the best for ourselves. This becomes then, an act of selfishness, but only in the highest sense.

It is interesting to note that Smith’s book primarily entails a description of the seven virtues, which, in addition to the Master virtue of rationality, are viewed as the cornerstones of her ethics. It is almost as if the Nicomachean Ethics have been rewritten in the language of a 20th century Objectivist. Smith even addresses friendship in the appendix of the book, describing it in the Aristotelian terms, which Aristotle himself used, “By friendship, I mean a relationship between two people marked by mutual esteem and affection, concern for the other’s well-being, pleasure in the other’s company and comparatively intimate levels of communication.” She goes on to state “I am here concerned with what Aristotle considers the best and truest type of friendship, sometimes called friendship of character.”

Smith and Rand seem to have different interpretations of Aristotle, and Smith seems to soften and humanize the seemingly more base egoism of Rand. Smith herself does claim that “for a rational egoist, to value something is to recognize it as in one’s interest, as personally beneficial in some way. Loving another person, in so far as it reflects valuing, is a thoroughly self-interested proposition.” These two statements sound very much like the position of Ayn Rand. Much of Smith’s book interprets Aristotle in a light with which I am far more sympathetic than I am with Rand. I will conclude this discussion of Rand’s philosophy with a quote from Atlas Shrugged taken from a speech of John Galt in which the bulk of her theory is expounded:

The symbol of all relationships among men, the moral symbol of respect for human beings, is the trader. Just as he does not give his work except in trade for material values, so he does not give the values of his spirit — his love, his friendship his esteem — except in payment and in trade for human virtues, in payment for his own selfish pleasure…. (pg.949)

Do you ask what moral obligation that I owe to my fellow men? None — except the obligation I owe to myself, to material objects, and to all of existence: rationality. I seek or desire nothing from them except such relations as they care to enter of their own voluntary choice. It is only with their mind that I can deal and only for my own self interest. I win by means of nothing but logic and I surrender to nothing but logic. (pg.948)

To love is to value. Love is the expression of one’s values, the greatest reward you can earn for the moral qualities you have achieved in your character and person, the emotional price paid by one man for the joy he receives from the virtues of another. (pg.959).

Ayn Rand said of Aristotle, “If there is a philosophical Atlas who carries the whole of Western civilization on his shoulders, it is Aristotle”. “Whatever intellectual progress man had achieved rests on his achievements”. (Review of J. H. Randall’s Aristotle, “The Objectivist Newsletter”, May 1963, 18) From these statements it is clear that he has had a profound influence upon her and her philosophy. She was also greatly influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche, though doesn’t seem to wish to acknowledge this fact. While I won’t claim that all of her conceptions of self-interest are Nietzschean, I do think there is a significant Nietzschean influence, which may be why her arguments do not seem fully consistent with Aristotle. The ethics of ’Objectivism’ has been regarded as self interest by Rand and is commonly referred to as rational egoism. It is interesting that she claims to find support and justification for this ethical theory in the teachings of Aristotle, with no mention of Nietzsche, “The only philosophical debt I can acknowledge is to Aristotle. I most emphatically disagree with a great many parts of his philosophy — but his definition of the laws of logic, and of the means of human knowledge is so great an achievement that his errors are irrelevant by comparison.” She goes on to claim that “there is no future for the world except through a rebirth of the Aristotelian approach to philosophy.” Leonard Peikoff, a student and follower of Rand for thirty years writes, “Aristotle and Objectivism agree on fundamentals and as a result on the affirmation of the reality of existence, of the sovereignty of reason, and of the splendor of man.”

In Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, Rand writes, “Let us note the radical difference between Aristotle’s view of concepts, and the objectivist view, particularly in regard to the issue of essential characteristics. It is Aristotle who first formulated the principles of correct definition. It is Aristotle who identified the fact that only concretes exist. But Aristotle held that definitions refer to metaphysical essences, which exist in concretes as a special element or formative power, and he held that the process of concept-formation depends on a kind of direct intuition by which man’s mind grasps these essences and forms concepts accordingly. Aristotle regarded essence as metaphysical; objectivism regards it as the epistemological.

Placing Aristotle contextually in the great Athenian city-state has been necessary for a fuller appreciation of, and more accurate interpretation of, his writings. So too with Rand, a few words of contextualization are in order. Born Alissa Rosenbloom, in 1905 in St. Petersburg, Russia, where the social horizons of human possibility were shrinking around her. Her father had become a chemist, despite quotas on Jews studying at the university. She witnessed the first shots of the Russian Revolution from her balcony in 1917, and her family was virtually overnight reduced to crushing poverty. While a student at Petrograd State University, she was expelled at the age of 17 as anti-proletariat. Managing to escape Russia, she arrived in the United States in 1926. Her first novel, We the Living (1936) portrays life in post-communist Russia. In the preface Rand points out the autobiographical similarities between her own youth and the life of her protagonist. The Fountainhead, her first major success, was published in 1943 and epitomized American individualism in the character of architect Howard Roark. This novel first presented Rand’s provocative morality of rational egoism, in which Roark eventually triumphs over every form of “spiritual collectivism.”

In comparison to Aristotle, Ayn Rand’s driving relentless egoistic selfishness seems harsh, competitive, and antisocial, probably arising from the psychological trauma she must have experienced in her youth. She does allow for friendship, and even for love, but gives it value only when one is able to clearly see the benefit to self of the relationship. When one’s conception of relationship is that of trader, and one is continually asking the question—what’s in this for me? — the opportunity to achieve the type of character friendship envisioned by Aristotle seems remote, if not impossible. Egoism and selfishness in the Aristotelian sense seems rather to be only discernible when one carefully dissects man’s activities and relationships, recognizing that his ultimate goal is his own enlightenment, virtuousness, and eudaimonia. The actual behaviors and the day-to-day living of such a man would not be observable as selfishly motivated nor egoistic. For Aristotle, self-love and selfishness motivate us only in so far as the achievement of virtuousness and nobility result in our own self-fulfillment and happiness or eudaimonia. Rand’s egoism is overriding, demanding, and in-your-face. It is all about self-interest, self-preservation, and self-promotion. That she is also able to view the ultimate human goal as fulfillment of self does not justify drawing any significant similarity with Aristotle. These are two very different views of the self , its motivation, and its relationship to others. I see little or no justification for Rand’s claim to Aristotelianism as the root of her rational egoism or of her objectivism.