Kurdish Sun Rising?

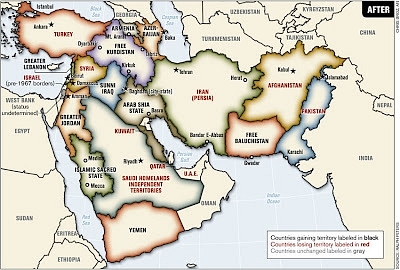

In the ebb and flow of History, Kurdish fortunes seem to have risen yet again. After being persecuted by their neighbours for centuries, after their betrayal at Lausanne, and after the horrors of Halabja, their hope for an independent Kurdistan, unthinkable even a decade ago, is closer to fruition than ever before.

The Kurdish people are spread over an area approximately the size of Japan across modern-day Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. An indigenous ethnic group, they speak Kurdish, an Indo-Iranian language. It is been debated whether there ever existed a Kurdistan in ancient times, but the closest it has come to recognition in modern times is when Iraqi Kurdistan was granted autonomy in 1970; its status was reconfirmed by the new Iraqi government in 2005.

The defeat of Saddam Hussein’s forces and the collapse of the Iraqi totalitarian state in 2003 took the cork out of the bottle of sectarian violence in Iraq; Iraq was divided along Sunni and Shia lines, adding to the already tense Shia-Sunni stand-off between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Arab weakness caused by sectarian differences increased relative Kurdish strength in the country, allowing it significant leeway in shaping post-war Iraq. In addition, the governments in Ankara, Damascus, and Tehran saw an autonomous Kurdistan as a tool by which to enervate the other traditional regional strongman, Baghdad.

The new Kurdish autonomous region has already taken up the task of forming a distinctive identity with gusto. If theories of nationalism are to believed, language and print are key ingredients in shaping a national identity; the Kurdish government has insisted on Kurdish being recognised alongside Arabic as a national language in the Iraqi constitution, and made it the default medium of education across schools and colleges in the Kurdish zone. In conjunction, Kurdish media has also experienced a boom in print, radio, as well as television.

Besides its own media, the Kurdish province also has its own flag and more importantly, its own regular militia. The peshmerga, Kurdish guerrilla fighters, have been transformed into a proper conventional army with an appropriate organisational hierarchy, uniform, and salary.

This new-found identity and assertiveness has been received with varying enthusiasm from its neighbours, and some have changed their minds since the early days of Kurdish autonomy. It is not clear if Kurdistan will become an independent country in the near future, but it has already overcome some odds previously thought to be insurmountable and has become an oasis of stability in a chaotic part of the world. Iran, Syria, and Turkey are keeping a close eye on not only the autonomous province in Iraq but also their own Kurds in an era of great change in the Middle East.

Kurdistan and Iraq

Iraqi Kurdistan has the lowest poverty rates in the country. Its relative distance from the violence engulfing the rest of Iraq has allowed the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) to focus more on development and as of 2004; the per capita income in the province was 25% higher than in the rest of Iraq. This has attracted many workers from the rest of Iraq to the little Kurdish oasis of peace. Iraqi Kurdistan is also blessed with the sixth largest oil reserves in the world, as well as significant quantities of coal, copper, gold, iron, limestone, marble, rock sulphur, and zinc.

The KRG has had increasingly acrimonious disagreements with the Iraqi central government. Baghdad resents the increasing autonomy and wealth the KRG is enjoying, while the Kurds are tired of their wealth being expropriated by rulers in Baghdad without investing in the development of Kurdish areas or people. Baghdad is also resentful of the KRG’s independent Department of Foreign Affairs which reduces Iraq’s control over its wayward province even more. In addition, the Iraqi central government is certainly not pleased with the KRG’s publicity campaign – The Other Iraq – to attract investors, highlighting the stability and security of the province.

Tensions between Hewlêr and Baghdad came to a head in 2011 over disputed territory between the two. The KRG claims the oil-rich regions of Mosul and Kirkuk, which Baghdad has steadfastly denied. In 2012, the Iraqi government ordered the KRG to transfer control of the peshmerga to Baghdad or face the consequences of attempted secession. Hewlêr refused, and clashes between Iraqi forces and the peshmerga in November that year left ten wounded and two dead.

Hewlêr was also incensed when Turkey and Iran shelled Iraqi Kurdistan in 2008 and 2010 respectively and Baghdad did little to defend Iraqi territory. Turkey was taking military action against the Parti Karkerani Kurdistan (PKK) and Iran against the Partiya Jiyana Azad a Kurdistanê (PJAK), the former listed as a terrorist organisation by the United Nations, Europe, and the United States, and the latter an offshoot of the former. Baghdad intended to de-fang the KRG via Tehran and Ankara, but operations lasted only a few days and the KRG saw the incidents as only further evidence of their second-class status in Iraq.

Kurdistan and Turkey

With Akhand Kurdistan claiming up to 40% of Anatolia, Turkey would be the last country anyone would expect to be warming up to the KRG. The success of the Kurds in putting their house in order should have been more cause for worry to Ankara since a viable Kurdish state was appearing on their border – who was to say it would not light the passion of Kurds in Turkey for similar greater autonomy? In days past, Iraq’s territorial integrity was of vital importance to Turkey, but with shifting political winds, Ankara’s thoughts may have changed.

Oil, as everyone knows, is a great aphrodisiac among nations; in the Iraqi case, it is an important factor in both the cohesiveness and fissiparity of the country. The KRG’s increasing autonomy in a region richly blessed with oil has not passed unnoticed by national capitals or corporate leaders worldwide. Oil multinationals have been setting up shop in Iraqi Kurdistan even in areas disputed between Hewlêr and Baghdad. Turkey has even opened a consulate in the capital city of the Kurdish region and trade between the KRG and Ankara was said to touch $9 billion by 2009.

As of 2012, over a thousand Turkish companies operated in Iraqi Kurdistan, alongside American, Russian, French, Chinese, and others. Kurdish relations with these multinationals provides a measure of security in case violence were to break out in Iraq; foreign interests, particularly regional and superpower ones, could well dissuade Arab Iraq from pursuing any civil war too aggressively into Kurdistan.

Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan need each other; for the former, the oil and gas the latter sells not only increases the diversity of sources but is also cheaper than Russian or Iranian energy, and for the latter, Turkey is the easiest conduit to the Mediterranean and the international market. However, Ankara’s hunger for energy could have destabilising effects on the region: if Turkey still believes a united Iraq is in its (and the region’s) better interests, it must be careful that the KRG’s energy revenues do not encourage it down a path towards independence. Ankara has already signed deals (for one gas and two oil pipelines) with Hewlêr directly rather than go through Baghdad, and rumours abound that the income distribution arrangement between the two Iraqi cities is not being kept meticulously by either side. Furthermore, Turkey must consider that while a weak Baghdad seemed a rational strategic goal in the past, a stronger Iran, particularly a nuclear one, may demand a resurrection of Iraqi power.

Kurdistan and Iran

Like in every other country in the region with a significant Kurdish minority, Kurds in Iran have a long history of oppression. However, Tehran has warmed up to Iraqi Kurdistan in recent times, call for improved ties with the KRG and greater economic cooperation, particularly in agriculture and power. Trade between Iran and the autonomous province of Iraqi Kurdistan has already hit $8 billion.

While Hewlêr is concerned about Iranian shelling of a few of its border towns, it is also aware that there is little it can do on its own and help from Baghdad is unimaginable. Furthermore, with Kurdistan’s future with Iraq and Turkey uncertain, it would be unwise for Hewlêr to spurn any opportunities for friendship with Tehran. Iraqi Kurdistan also needs Iranian expertise in developing its mineral wealth: there are already over 500 Iranian companies in the province and the KRG is doing its best to attract more Iranian technicians to train its people and build its infrastructure.

Tehran, on the other hand, may feel more comfortable with a Shia-dominated Iraq on its border but needs Kurdistan as well for trade in an era of sanctions. A friendly yet weaker neighbour would also be less likely to allow its soil to be used as a staging ground for state or non-state anti-Iran forces. Furthermore, in the old cultural animosity between Persians and their Arab neighbours, Kurds, who have as much reason to resent Arabs, might be useful allies.

Kurdistan and the Syrian Conflict

While oil and the Kurds’ neighbours are reasonably predictable, the civil war in Syria has become a complete wildcard. Turkey’s traditionally strong relations with its southern neighbour have snapped and in retaliation, Damascus has given Syrian Kurds a free hand to establish themselves in the north by the border with Turkey. Syrian Kurds, affiliated with a PKK offshoot known as the Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat (PYD), have mostly remained out of the conflict but are equally wary of Ankara’s close ties to the Syrian opposition which consists of several Sunni Islamist factions.

Some Syrian Kurds have voiced a desire for autonomy after the war, like their brethren enjoy in Iraq, while others have called for outright independence. With a unified and centralised Syria seeming more impossible with each passing day, Turkey hopes that its close relations with the KRG will be of some help when it comes time to negotiate with the PYD. If Syria’s Kurds manage to break away, there emerges the question of whether they would consider merging with an independent Iraqi Kurdistan, a perturbing prospect for all of Kurdistan’s neighbours. In the past, Turkey has threatened military action in such a scenario, but Ankara’s relations with the Kurds have changed dramatically in the past few years.

The Parti Karkerani Kurdistan

Ankara’s recently struck peace with the PKK can in many ways be seen as the first blow of the next potential conflict in the Middle East. After months of secret negotiations (probably assisted by KRG officials behind the scenes), Recep Tayyip Erdoğan struck a peace deal with imprisoned Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan. Under the publicly known stipulations of this agreement, the PKK will leave Anatolia to return to their bases in Iraqi Kurdistan. Öcalan has also explicitly abandoned the idea of an autonomous or independent Kurdish state being carved out of Turkey.

The PKK’s return to Iraq has been condemned by Syria, Iran and Baghdad, each worried that the returning numbers would swell the ranks and consolidate the energies of the respective Kurdish factions arrayed against them, the PJAK in Iran, the PYD in Syria, and the KRG militia in Iraq. In fact, Turkish intelligence has claimed that Iran has offered the PKK more supplies if they remained in Turkey.

The KRG, for its part, has demanded the utmost loyalty of the PKK to the Kurdish government and is keeping close tabs on the group’s activities. The peace deal with Turkey did not stipulate that the PKK disarm, and an armed and experienced militia outside the control of the KRG would pose a threat to its stability. Furthermore, Hewlêr is concerned that a trigger-happy PKK might create problems for its diplomacy with Iran and Turkey and demonstrate to the world that the KRG is not in control of its own region. Such spasmodic violence can undermine the entire Kurdish project by scaring away much-needed international good will and investors.

Kurdistan vs. Kurdistan

A Kurd’s greatest enemy is another Kurd. Despite their common oppression, the Kurds have maintained innumerable factions that fight against each other. Outside powers have frequently exploited this to the incalculable detriment of the Kurds, and even today, the situation is hardly different. Despite an institutional set-up in Hewlêr, there is worry in some corners that Kurdish politics is, as it has always been, tribal and personal.

For example, Turkey has developed relations with the Partîya Demokrata Kurdistan (PDK) led by the Massoud Barzani, while Iran enjoys closer ties to the PDK’s coalition partner, the Yeketî Niştîmanî Kurdistan, also known as the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), led by Jalal Talabani. This arrangement appears to leave the KRG’s entire foreign policy to the mercy of electoral calculations and personal outcomes – if the PUK were to become a more valuable member of the same coalition in the next election, Iraqi Kurdistan could be humming a Persian tune. Such vicissitudes are not uncommon in other countries either, but few exhibit drastic differences in their world views as exist between the PDK and the PUK, despite their rhetoric. The Kurdish Opposition, the Gorran Movement headed by Nawshirwan Mustafa, is a new and relatively unknown political force, though most of its members were formerly of the PUK.

The Relationship That Dare Not Speak Its Name – Kurdistan and Israel

Kurdistan’s one relationship that is at once profitable and a liability is the one with Israel. The Jewish state has supported Kurds for a long time, the persecuted ethnic group an ulcer for the Arab enemies. Israeli support for the Kurdish cause dried up very quickly due to logistical reasons after the Shah of Ira, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, signed the Algiers Agreement in 1975 that denied Israel Iranian staging grounds for running supplies to Iraqi Kurds. Since then, Israeli ties to the Kurds have remained small and in the shadows.

The state of Israel’s relations with its Arab neighbours is no secret. As Turkey turned away from Europe and towards the Middle East in recent years, particularly after the MV Mavi Marmara incident in 2010, its relations with Israel have become strained as well. In the midst of this hostility, Kurdish relations with Israel would set off alarm bells in every regional capital and may even bring to bear economic and military pressure upon Hewlêr. Given the sheer volume of Turkish and Iranian investments into the Kurdish economy, the KRG would be unwise to presently pursue closer ties with Israel and antagonise the neighbours.

That said, there is ample support for Israel among the people. In a recent University of Kurdistan debate held in Hewlêr, students argued strenuously for ties with Jerusalem. Kurdish independence would please Jerusalem very much too, giving them the opportunity to cultivate an ally in the heart of hostile territory. As with many other states sensitive to religious grand-standing, Israel maintains low-profile assistance to the KRG, military as well as economic.

What Does The Future Hold?

The Kurdish autonomous region may not be ready for independence in the immediate future, its weak military and urgent need for economic development delaying any thoughts of breaking away from Iraq. Nevertheless, as its economic strength grows and it achieves basic infrastructural goals for its people, more and more Kurds will question the utility of staying within an Arab Iraq.

There are hints that the KRG is deeply concerned about its military weakness vis-a-vis its neighbours. During a recent visit to Washington, it is rumoured that Barzani sought security guarantees for the Kurdish region but was rebuffed by the Obama administration. There is no doubt that the Kurds have proven to be the West’s most reliable ally in the region, but the United States has until recently not encouraged Kurdish separatism out of deference to fellow NATO member Turkey’s wishes. However, with Ankara singing a different tune and Syria collapsing to Islamists, the next President might see the value of an independent Kurdistan.

As regional alliances shift to balance the realities of the new Middle East, Kurdistan may have its best opportunity for independence since Sèvres. If the KRG wishes to take it, they must focus on developing their economy further and reassuring at least some of their neighbours that they have no irredentist ambitions. Building up the military will be tricky as an autonomous province and will warn everyone of the potential bid for independence. Yet Iraq and Turkey, who have already had a taste of battle with the peshmerga, already know that the Kurds can be a formidable enemy even without international support or a fully-fledged conventional army.

Most importantly for the Kurds, as has always been the case in their history, can the different factions – PKK, PYD, PJAK, PDK, PUK, Gorran Movement, and others – get along with each other to make an independent state a worthwhile venture?