Hagalu Vesha: How The Budaga Jangamas Of Hampi Keep Their Folk Art And The Tale Of Kishkinda Alive

It was in Hampi that Rama met Hanuman. And it was from here that the journey of the ‘Vanara Sena’ to bring back Sita began.

Here’s how a tribal folk art form of ‘Hagalu Vesha’ recreates this tale in the Kishkinda of yore.

Once upon a time in history, much before it was the seat of power of the greatest south Indian Hindu empire, Hampi was referred to as Kishkinda, the Kingdom of the Vanaras (monkey-like beings).

It was here that Rama and Lakshmana got the support of the vanaras, led by Hanuman, and from here they marched towards Lanka to get Sita back.

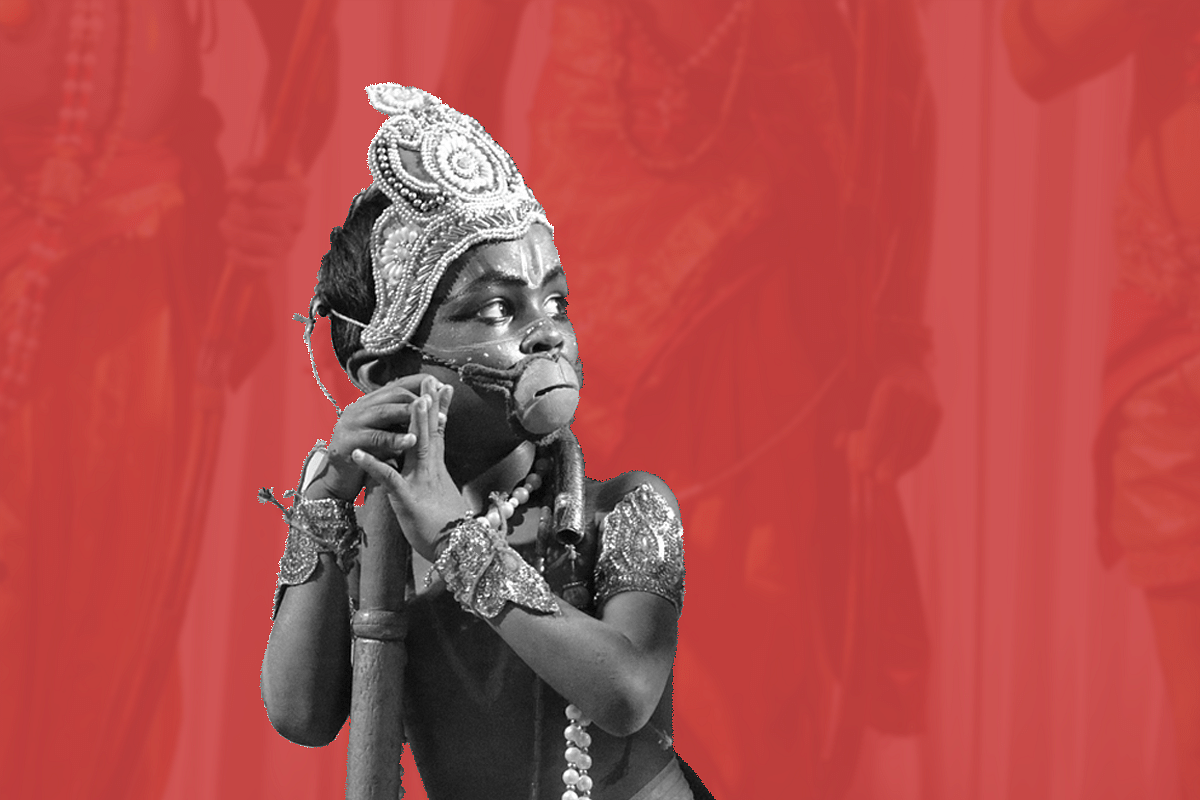

Against the backdrop of the hills, as the sun rises in the land of Krishnadevaraya, two monkeys jump around wielding gadhas and prance around in their colourful attire, their crowns and jewels bedazzling, their tails swinging in the air.

‘Loka loka loka …vaanaraa loka…Loka loka loka …vaanara loka!

Kallu bilupugale nammaya naadu…

Julu julu areyuvudey ampeya oleyu…

Koti, karadi, aane, jinkeya loka…loka loka loka... vaanara loka!

Thus begins the singer, who also plays the harmonium, as the feet-tapping percussion draws even those who know not the language into the performance. For the next hour or so, one is lost witnessing these folk artists transform the space into the Kishkinda of yore.

The context is set with the battle that ensued between the brothers Vali and Sugreeva that had Sugreeva taking refuge atop the mountain Malatyada.

You are mesmerised watching the characters prance around like monkeys, with the jhan jhan of the ghungrus setting the tempo, when without a warning there is a silence followed by a melodious call for ‘Rama…’. And suddenly Rama emerges from between two distant boulders as the singer breaks out into a bhajan in praise of the Lord of Ayodhya.

Hanuman, on spotting Rama and Lakshmana wandering around, asks them who they are and why they are here — fearing they are the spies of the evil Vali. When they reveal their identity, he takes them to Sugreeva.

The brothers then help Sugreeva regain his kingdom and in return, the entire vaanara sena helps Rama get his wife Sita back from Lanka. There aren’t many who wouldn’t know these tales. But to watch a rustic folk presentation of the same story in the land where the tale is said to have actually happened lends a magic of its own.

Hanumayana is a troupe of tribal folk artists who have been performing this mime act of Hagalu Vesha for generations now.

Hagalu Vesha is a theatrical performing art whereby the artists paint and disguise themselves as different characters either from epics or other fictional work.

Traditionally, they belong to the Budaga Jangama nomadic tribe and have been practising this for generations. Hagalu Vesha literally translates to ‘day-role’, implying that these stories are mainly performed during the day.

No stage, no lighting, no green rooms. All they need is an open space and they are all set to perform. While the musician duo squats down at one end, the characters enter the space one by one as the narrator brings the tale alive with his singing, interspersed with narration.

K Ramu of Hampi’s Hagalu Vesha Hanumayana group learnt the art from his father and has been performing since 2000. “We may have changed the way we do it, the form and format may have changed — but what we inherited as art has stayed intact — he tales are intact,” says Ramu. His uncle and brother-in-law are the ones at the harmonium and tabla, which was earlier handled by his father.

This performance is staged at one of the many melas in the regions and each mela has its designated villages.

Most of these tribes in Karnataka are found in and around Bellary and neighbouring districts like Koppala. As the region borders Andhra Pradesh, the tribes are fluent in the local language Kannada as well as Telugu but perform predominantly in Kannada.

As a nomadic tribe, the Budaga Jangamas are traditionally known to move from village to village earning their living out of these performances.

While they now perform at events and for commissioned audiences, the tribe traditionally pitched its tent in a village where it stayed for around a fortnight during which it performed every morning in different streets of the village. They would then collect whatever was offered as appreciation — from grain to money — and move on to the next village.

The themes range from mythology to social awareness. It is said that during the time of Basavanna, in the 12th century, the tribe spread the thoughts of the poet-saint through their acts.

While their numbers have certainly dwindled, troupes like these still try and encourage their tribesmen to not give up their cultural heritage. A school drop-out himself, Ramu wishes the youngsters from his community sustain this folk art even as they take to education.

‘We have travelled the length and breadth of the country performing this tale of Hanumayana, and are doing what we can to keep our art alive,” says Ramu. ‘Kali beku adare kaleyu beku (Education is important but so is art). And one can be better off if one has education to back one's art,” he adds.

But those who take to formal education find it difficult to adapt to this way of life, confesses Ramu.

From their movements to their language, everything changes. And this art form needs a certain rawness, which goes missing once one is ‘educated’ and distant from one's traditional roots, he opines.

In a bid to bridge this gap, the elders ensure that they ‘catch them young’.

Like six-year-old Raghava, who caught everyone’s attention and was the most sought after ‘vaanara’ after the performance that Hanumayana put up during the Swarajya heritage tour to Hampi last year.

"Raghava was touring with us for some time just watching us perform. So they learn not just by practicing but also by being with us too,” explains Ramu. "As he grows up he will soon be ‘promoted’ to another character and we will find another young boy to play the little vaanara,” elaborates Ramu.

Ramu has also been a member of the academy of folk art in Karnataka and has worked to get the art form its due recognition and support from the government.

While the central idea of Hagalu Vesha itself is disguise, it is their portrayal of female characters that personifies it.

From the gentle Sita to the scary and fierce Surpanaka, all female characters are played by men. ‘Women do not perform. The men don the ‘stree-vesha’ (female-role),” says Ramu.

The tales that they recreate are well-known ones, hence their audiences stay captivated even though they may not really catch the prose.

Recollecting the response they got in Nippani in Maharashtra, Ramu explains, “The language was incomprehensible but that was no barrier at all, as the applause and reception of the audience, which was in thousands, are unforgettable!”

Hagalu Vesha performances are loosely scripted and generally involve mime to a great extent with the narrator reciting the tale in the background. They are also called Bahurupis (Behrupiya – Hindi), which means one that dons many roles and implies disguise.

Their makeup is loud, their costumes shimmer strikingly, and their music is raw, rustic and earthy. But then that’s what sets them and their art apart!