Kashipath 2019 Day-8: A Symbol Of ‘Samanvaya’ On The Road To The Temples Of Khajuraho

On Day 8 of our Kashi Yatra, we stop over at Khajuraho — a land where we realise our civilisational depth as well as the lows to which we have sunk.

On Day 8, we hit the road to Khajuraho.

This is a day mostly spent in travelling through the roads in Madhya Pradesh. Occasionally, we stop to take photos and drone shots of the changing scenario of the roads.

Thanks to our trip partner, Savaari Car Rentals: You can now rent an affordable taxi almost anywhere in the country.

The landscape is quite alluring with its small water bodies, cattle grazing and houses with slates for their roofs.

Also, we come across small country markets. As we travel, I am going through my WhatsApp messages. In my college alumni group, a classmate just has asked me if I have gone to Ujjain Kali temple. We did not. We halted at Ujjain after a night darshan of Mahakaleshwar and left early morning.

We stop at a roadside hotel, quite small, for a cup of tea. This for us is somewhere in the middle of nowhere. Like in all such hotels, here too, we see a display of Gods and Goddesses.

The dominant figure is a seated cross-legged Thirthankara of the Jain Dharma. On the one side, there is a framed photo of Tirupati Balaji and on the other side is Goddess Kali on a strange temple.

Something is written in Hindi. Having grown up in the land ruled by Dravidian darkness, my ability to read Hindi is non-existent.

So, I seek the help of Karan, the budding Buddhist in the team. The boys in the stall answer — Ujjain Mahakali!

A Carl Jung would have called it ‘synchronicity’ while a Richard Dawkins would consider it as ‘petwhac’ (population of events that would have appeared coincidental)!

But think about the other aspect. We have here a Jain Thirthankara and a South Indian Vaishnavaite Deity with his consort and a Shakthic Goddess.

While, if we are to go into the Darshanas associated with each of these divine figures, each would look quite different from each other and may even look incompatible in one place. But for the Indian mind, all these represent the human ability to reach the transcendental and bring it into our own everyday realm, as they are all aspects of the same oneness.

The process is not a simple way of ‘all are one’ philosophy — a kind of religious Hakuna Matata but a local manifestation of a profound process — Samanvaya. So ultimately, despite the apparent incompatibility of the Darshanas — Jain and Vedic for example — we accept both as valid for their own seekers and acknowledge the great heights to which these systems have taken human spiritual experience to, thus enriching the Hindu cultural mosaic of the nation.

This is the reason why Hindu kings could have Jain wives and vice-versa. It should be remembered that two of the greatest achievements of Buddhism in India — Ajanta caves as well as Nalanda University — happened under the emperors who professed Vedic Dharma and were supported by them.

So, the display we see in the tea stall is as important as the Ellora caves housing Saivaite, Vaishnavaite, Jain and Buddhist divinities.

We then move on.

Inside the car, a lively discussion runs between Karan and Amar — both discussing how conducive the Buddhist doctrine is for the upholding of civilisation and the importance of taking the middle path.

Consciousness is either a flame that comes into existence and then goes off, or perhaps, it is the basic substratum — the eternal fluid from which arise the present physical universes and all our existence, just like bubbles and waves on the ocean. So, on the discussion goes, only to be stopped by a procession of people strangely dressed with crowns sitting on an elephant and an automobile decorated like a horse- drawn chariot.

We stop and ask what it is. It is a procession of Jains, householders and children, we are told. They are proceeding to welcome their monks. This is indeed a great land where, along with Samanvaya, theo-diversity forms the core of its being.

In a way, every religious stream here can be seen as a ‘religious minority’ with respect to ‘all others’.

Hence, the resistance to expansionist monopolistic theologies which operate with transnational funding is not ‘against minorities’, as often portrayed. Now, that is a fallacy. The resistance to proselytising is actually protecting of all the religious minorities.

We are now entering Khajuraho. It is already late in the evening.

Nothing had prepared us for what we could have seen — a small glimpse of the temple — before the guards announce that it is closing time and politely but firmly tell us to leave.

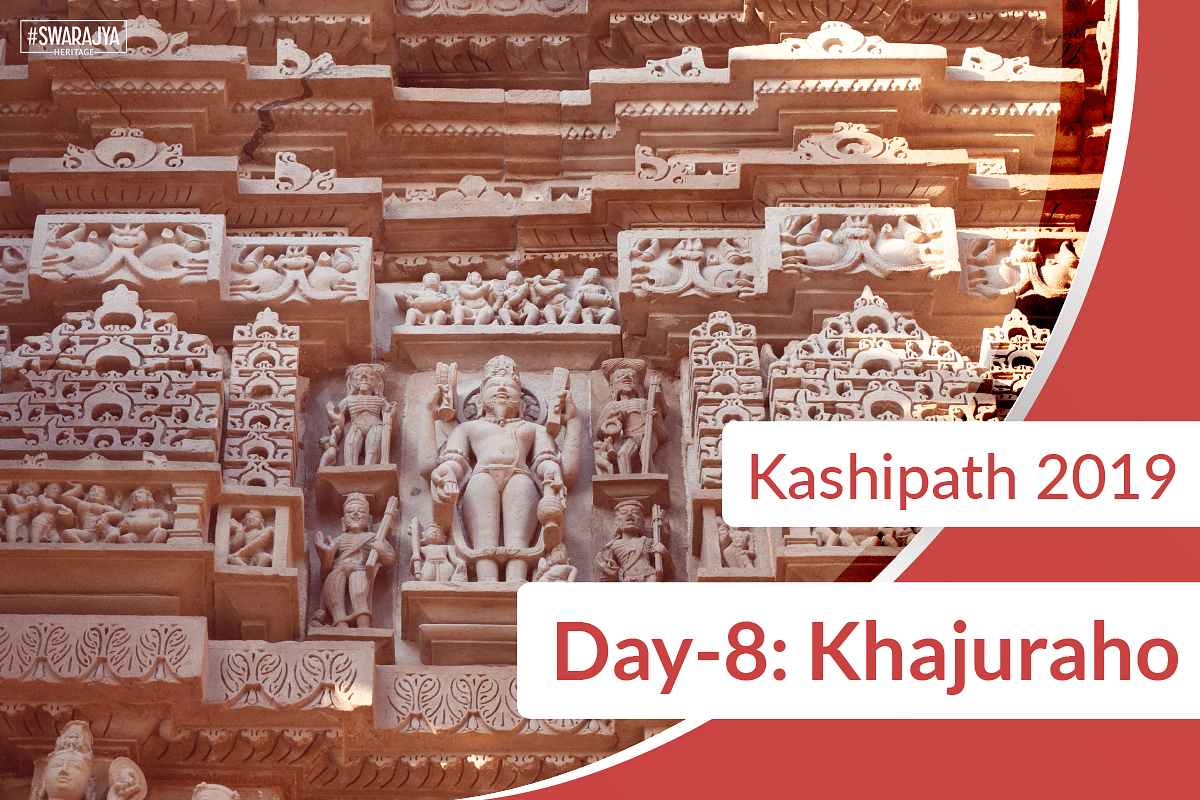

A fractal universe of the sacred in the grandest of the designs only chisels of artisans divine could have produced.

“There is a light and sound show. You can come at 6:30 pm,” they tell us. We leave and roam about. Unlike other ancient temple towns, here you do not see much of families. A few are there but not much.

Mostly teenagers and boys as well as a few girls in their 20s. The sellers as well as the host of ‘art galleries’ here sell mostly the replicas, books and picture cards of erotic sculptures which form only a fraction of the exquisite sculptures that populate the temples of Khajuraho. There is even an ‘erotic temple tour’ display in the town.

This is sad in more ways than one. Make no mistakes. Depiction of erotic themes in temple sculptures is in no way wrong. They are part of life. In a way, libido has been a major driving force in our lives, both as a species and as individuals.

Often, it is through the sublimating of libido that we reach out into deeper things. We do not consider ways of the libido as being ‘sinful’ pathways to hell.

We go through them all and accept them also as beautiful and as part of life — an important and even sacred part of life as we move towards the Divine.

But what is despicable in the bazaar streets of Khajuraho is the way the entire temple sculptures are marketed to tourists as if they are only filled with erotica.

It is cheap, vulgar self-denigration for the sake of profit.

Just look at all these miniature-to-big replicas of the erotic sculptures. What prevents us then from creating replicas of other sculptures? Where is the replica of Yajna-Varaha that is one of the finest heights of Khajuraho?

Where is a small model of a typical temple? Where is that definitive guide to the iconography of the temple sculptures?

If one can produce such replicas of one set of sculptures, then one should be able to produce others as well. But where are they?

I ask the shop-keeper with the help of Amar, who too is depressed by the sight of only one set of sculptures all over the bazaar street shops.

‘Varaha sculpture sir? No market for that,’ says the shop owner. But have you tried? We insist. No comes the cryptic answer. “Are you going to buy anything or not? I also have an illustrated Kama Sutra.” We understand we need to get out.

Time is up for the light and sound show.

Already, I feel depressed at what we have done to ourselves — bringing our self, down not just before foreigners but more importantly before our next generation. Now sitting at the light and sound show, I am worried I may further sink into depression when the show finally chronicles the destruction of the temples by Qutb-ud-din Aibak.

The show, however, is quite good. As one sits under the night sky and as lights illumine the temple gopuras around you with Vedic chants and rhythms of Indian musical instruments, you feel something very deep fill you completely.

It is a moving experience. The history is told eloquently. It states how the valorous emperors of the Chandela dynasty built these sacred monuments. It briefly but quite clearly explains the science of Hindu architecture.

It also brings out precisely the Hindu Darshana behind the temple sculptures. And then it also does not hesitate to touch the topic of Islamist invasions — as to how emperor Vidhyadara was able to defeat Muhammad of Ghazini when he invaded the first time, After three years, the encounter ended with the inability of Ghazini to break the resistance, which ended with the exchange of gifts.

The narrative does not talk about the ransacking of Khajuraho under Qutb-ud-din Aibak.

Instead, it portrays how the city slowly fell into decay and later disappeared into the jungles which reclaimed it, waiting to be re-discovered only during the colonial period.

But the narrative also clearly emphasises the fact that in one way or the other, the worship went on — even on a very moderate scale.

The show does not fail to give the description of Ibn Battuta of 14th century about Yogis with healing powers inhabiting the temple complexes.

So, at least the sound and light show of Khajuraho is quite true to its original magnificent vision and grandeur of almost unmatched human excellence. What about not mentioning Qutb-ud-din Aibak? It is okay. We need not come out with the sense of defeat.

For, we are not defeated. After all the invasions, we live and we live as proud Hindus — Saivaites, Vaishnavaites, Jains and Buddhists, Advaitins, Vishishtadvaitins, Dvaitins and Siddhantis, Nireswara Sankhyavadhis and what not.

We still live and let the show be the tribute to that civilisational life and its vitality — which it truly is. Not mentioning a plunderer and mass murderer in this context is not whitewashing.

We then come back. The roads are dark. A seller approaches us and whispers ‘Sir photos sir, photos…’

Ghaznis and Aibaks, who destroy our heritage, need not always come as invaders.

You can read the other Kashipath articles here.

This article is part of Swarajya’s Heritage Program. If you liked this article and would like us to do more such ones, consider being a sponsor – you can contribute as little as Rs 2,999. Read more here.