Ashok Chakra For Kashmiri Army Soldier, A Former Ikhwan: What Is Different About It?

Why we need to convince the alienated Kashmiris that Lance Naik Nazir Ahmad Wani is as much their hero as he is ours.

It’s a common saying among all those who live and work in Kashmir and those who simply observe it with focus, that there aren’t any positive role models and icons to be inspired by. Can the conferment of the highest award for gallantry in peacetime to a Kashmiri soldier of the Jammu and Kashmir Light Infantry (JAK LI) make that difference?

You can also read this article in Hindi- एक पूर्व इख्वान, कश्मीरी सैनिक को अशोक चक्र क्यों विशिष्ट है

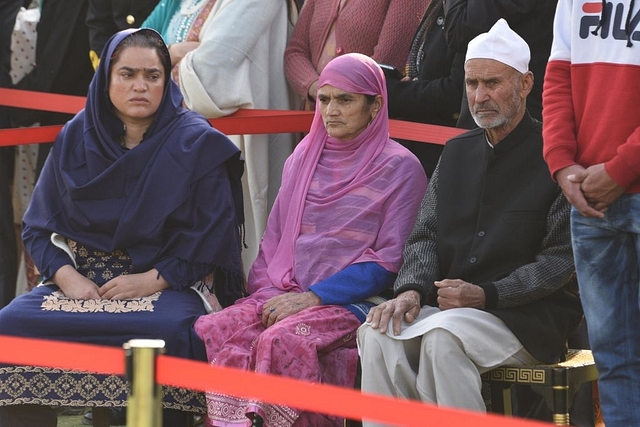

Lance Naik Nazir Ahmad Wani of Kulgam has been posthumously awarded the Ashok Chakra for gallantry displayed in operations by the President of India on the occasion of India’s seventieth Republic Day. His wife Mehjabeen and mother were seen by millions of people receiving the award at the recently-concluded ceremony preceding the parade at the regal Rajpath. It is not to be forgotten that late Lance Naik Wani was already a two-time awardee of the Sena Medal (Gallantry).

The Ashok Chakra was conferred on him due to his leading active role in the operation of another unit 34 RR, on 25 November 2018 in which he was involved in a close encounter with six terrorists. He killed two of them and injured one besides assisting in evacuation of an injured soldier. Lance Naik Wani succumbed to his injuries in the hospital. The media has been abuzz with a few other facts about the late hero. That he was a former Ikhwan, who got enrolled only in 2004 into 162 Infantry Battalion Territorial Army Jak LI (Home & Hearth) or 162 TA Bn JAK LI (H&H).

It is a mouthful for most people to even read the nomenclature of Lance Naik Wani’s unit let alone comprehend its numerous challenging tasks. The fact that he was a former Ikhwan is also lost on the current crop of soldiers and the public, and therefore needs a little explanation. What was a soldier from a TA (H&H) unit doing with an RR unit also needs to be understood to get a comprehensive picture of Lance Naik Wani’s stupendous achievements in the service of his nation and its army.

The story goes back to 1989-1990, when militancy had been triggered in Kashmir by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) as a part of its strategy of a ‘thousand cuts’ against India. A number of young Kashmiris were motivated by circumstances to cross into Pakistan-occupied Kashmir for training as militants to engage the Indian Army and police forces. When they returned, they fought against the Indian Army as they were mandated to by the ISI, but shortly disillusionment set in for the way they were treated by their Pakistani handlers, who never had a good word for the Kashmiris, and were more enamoured by foreign mercenaries.

Through the early nineties, even as they reluctantly fought, there was even greater disillusionment and progressively the army convinced them to surrender and help in its cause to target and neutralise the large number of foreign terrorists (FTs). The services of these mercenaries had been garnered by the ISI after the end of the Soviet-Afghan War in Afghanistan.

By 1994, they were formed into three groups, one each in mainly North Kashmir’s Bandipora area and South Kashmir’s Anantnag and Kulgam, plus one dedicated with Jammu and Kashmir Police’s (JKP) newly set up Special Operations Group. There were no geographical restrictions on them to stay in these areas and they worked in close cooperation with the newly-raised units of Rashtriya Rifles (RR) and some regular units of the Indian Army. Their task was to operate in small groups with the army and the JKP, bringing to the counter terrorist (CT) operations their immense knowledge of local conditions of ground, demography, ideology and culture mixed with their ability to handle weapons and act tactically in various situations.

They proved an invaluable asset and between 1994 and 1996 helped in neutralising most of the FTs. They became what in CT operations parlance is referred as counter groups; a concept followed by most security forces (SF) operating anywhere in such an operational environment. The group was called the Ikhwan-ul Muslimeen and the members were colloquially called Ikhwans (Ikhwan in Arabic stands for brothers).

The two most prominent leaders of the group were Mohammad Yusuf Parray, also known as Kuka Parray, a folk singer from Hajen in Bandipora who led the North Kashmir sub group, and Liaqat Khan of Anantnag who led the South Kashmir group. Of course many more personalities among them are well known in Kashmir, such as Usman Majeed and Javed Ahmad Shah (killed by terrorists in August 2003).

Subsequent to the elections of 1996 which the Ikhwan helped the SF to secure, they continued with the assistance to the SF but the intention of converting them to a political role did not fructify because they were not trusted by the people in an environment, where alienation was high. Kuka Parray did finally secure a seat in the elections as did Usman Majeed but there was no sustained effort to take this forward as a political campaign.

Parray was killed in September 2003 and the movement fell into disarray. Liaqat Khan in South Kashmir led the Ikhwan in South Kashmir but his political conversion too did not succeed. Without doubt the Ikhwan helped the SF to control the militancy but their conduct and alignment with the SF was never appreciated by the people from whom they remained progressively more alienated.

Lance Naik Nazir Ahmad Wani being from Kulgam was a part of the South Kashmir Ikhwan. It was only in 2003-2004 that a major decision was taken by the government of India to raise eight TA (H&H) units on the ‘son of the soil’ concept. This meant that these units would be manned by only locals, who would be permanently embodied for better employment and would assist the RR and other units in small groups. Their task was not just CT operations but also military civic action to aid the local population under Operation Sadbhavana.

Having a better orientation to local needs and sentiments they guided the RR and other units in the outreach to the people. That is an essential part of any CT campaign where the people remain the centre of gravity. This was the opportunity that Lance Naik Wani took to enroll in the new exclusive unit raised for the Ikhwans; it was titled 162 TA Bn JAK LI (H&H). As part of his duties Lance Naik Wani progressively remained attached to several units of the RR rendering close assistance in operations, liaison and intelligence.

The correct appreciation of an effective TA (H&H) soldier’s role in the success of the RR operations can be made from the fact that such soldiers are attached to these units. The moment an encounter commences, these are the very people who get to the spot in a matter of minutes, doing necessary guidance, liaising with local sarpanches, helping to take the civilians out of house where they may be held hostage and generally advising the officers leading the operation. That puts them in harm’s way once too often. Lance Naik Wani had, therefore, virtually put his life on the line.

Survived by his wife and two sons, plus his parents, it is not certain how the family is going to handle this rare honour conferred on Lance Naik Wani. In South Kashmir’s deeply alienated environment, where the killing of local army jawans and policemen has been the focus of the ISI strategy, it may be unsafe for them to live. Kulgam district is where Lt Ummar Fayaz of 2 Rajputana Rifles was dragged out of his cousin’s wedding and shot dead in 2017.

Yet, as someone who loves Kashmir and Kashmiris, I was happy that the courageous feats of a Kashmiri hero could be heard by the people of India. There are many in Kashmir who are alienated from the rest of the nation and yet many who are willing to sacrifice their life for it. Between this paradox, Kashmir continues to exist.

It is up to us how we handle the martyrdom of Lance Naik Wani, Ashok Chakra (posthumous), to make a comprehensive hero and icon for the nation. We need to convince the alienated Kashmiris that Nazir Ahmad Wani is as much their hero as he is ours.