Assam’s 4 Million Exclusions From NRC List May Well Be An Under-Estimate

Assam’s problem is not Assam’s alone. It is a national problem.

What we need is a sensible policy that focuses on sending back some illegals, while absorbing the bulk of them with temporary work permits, which can be converted to citizenship and permanent residency over time.

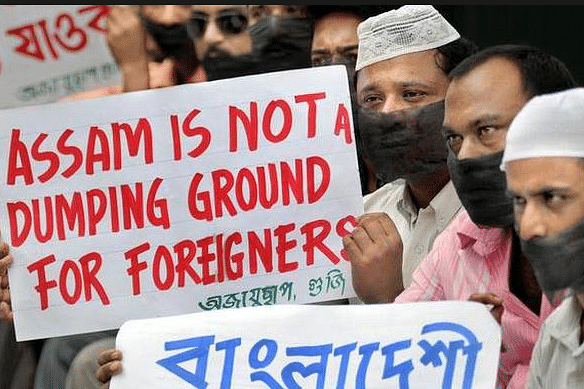

There has been a political and media uproar over the publication of the draft National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam yesterday (30 July), with 40 lakh people being identified as non-citizens staying on illegally. While these people can still file objections and have a right to appeal against the decision of the Registrar General of India (which did the head-count based on the production of a list of accepted documents), most of the comments that followed made no sense.

Large parts of the media claimed 40 lakh (four million) Indians were being declared stateless. This is bunkum. One can doubt whether all the 40 lakh people left out of the NRC are illegals, but the bulk of them are certainly not Indian citizens. At best one can term them long-term illegal residents, perhaps entitled to citizenship on the basis of naturalisation. And even this does not apply to the whole lot.

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee went one better, and claimed that “they are turning Indian people into refugees in their own country.” She threatened to send a team to Assam and “if necessary, I will go there too”. To repeat, it is by no means certain that those deleted from the NRC are Indian citizens, and Banerjee is hardly going to cool tempers by stirring the communal pot in Assam. In fact, if she looks in her own backyard, she may find that illegal Bangladeshi immigrants came in droves in West Bengal too. It is another matter that they constitute her vote bank, and she has no interest in doing her duty as head of the state to separate citizens from illegals.

Then we had the Home Minister, Rajnath Singh, claiming that the government had nothing to do with the NRC and exclusions. He told the Rajya Sabha: “in publishing NRC, the government has done nothing. Everything is being done as per Supreme Court order. The allegation of the opposition against the government is baseless.”

While this may technically be true, the reality is that all governments – from Rajiv Gandhi’s down to Narendra Modi’s – are committed to identifying illegal Bangaldeshi immigrants as per the Assam accord of 1985. So, to claim that this is all the Supreme Court’s doing is rubbish. The Congress and “secular” parties may want to play saviours to Bangladeshi Muslims by talking of the “human rights” of those settled illegally in Assam’s Barak Valley, but the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has promised to send back these illegals. Narendra Modi talked about deporting the illegals on his 2014 campaign trail.

The question the BJP needs to ask itself is this: if it is truly a Hindu party, then why is it shy of fighting for their rights and claiming that it is merely following Supreme Court orders? It needs to protect the rights of two kinds of Hindus – those who are already Indian citizens in eastern India, and feel threatened by a demographic influx from Bangladesh; and the second is to provide sanctuary and eventually citizenship to the Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains and other minorities, who had to flee that country due to persecution by the Muslim majority.

Though illegal Bangladeshi immigrants are of two types – Muslims and Hindus and other minorities – there is absolutely no moral reason to treat those being persecuted in that country and those coming here for better economic prospects on the same plane. The former must have precedence to citizenship, and if at all the NRC needs a tweak, it is to recognise this reality between the persecuted and the persecutors.

This was, in fact, the logic of the two notifications the NDA government issued in 2015 and 2016, which allowed Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan from being deported under the 1946 Foreigners Act and the 1920 Passport (Entry into India) Act. The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill 2016, introduced in the Lok Sabha in July 2016, sought to legalise these notifications through legislation, but ran into the usual roadblocks of the “secularistas”.

In Assam, while the locals may be happy to see both Bengali Hindus and Muslims evicted, there is no moral justification to treat the two types of refugees on a par.

A few other points also need to be made about the publication of the first NRC draft in Assam.

One, contrary to fake media outrage over the 40 lakh figure, the chances are that even this figure is an underestimate. In 2003, then Home Minister L K Advani had estimated the size of illegal Bangaldeshi immigranst at 15 million (see this report, page 13). So, the four million indicated by the NRC is nothing to get excited about.

The plan to publish the list has been known for more than two years now, and hence the probability is high that those who are truly illegals might have moved to places outside Assam where the NRC is not being implemented. Among them: West Bengal, Bihar, and many cities in northern and southern India, including Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru. If the Surpeme Court and the government have the gumption, the logical way forward is to extend the NRC process to all of India, especially big metros, and not just restrict it to Assam. But few political parties, including the BJP, have the stomach for this.

Two, the illegal immigration problem is largely a Muslim problem even though both Hindus and Muslims came over from Bangladesh. A cursory look at the decadal Census tells us why. Between 2001 and 2011, while the total population of Assam rose 17 per cent, from 26.65 million to 31.20 million, this surge was led by Muslims, whose population soared by nearly 30 per cent, against just under 11 per cent for Hindus. The Muslim rate of growth is more than two-and-a-half times the Hindu rate, and that could not have been possible without illegal immigration. Says a report by the Centre for Policy Studies, “of 45.5 lakh additional persons counted in Assam in this decade, 24.4 lakh are Muslims, and only 18.8 lakh Hindus. Looked at in another way, of every 100 persons added to the population in 2001-2011, 54 are Muslims and 41 Hindus.” Of the remaining five, four are Christians and one from other minority religions. Between 1971, the cutoff year for the Assam accord, and 2011, the Muslim share in Assam’s population zoomed from 24.6 per cent to 34.2 per cent. Make no mistake, Assam is on the verge of a huge religious demographic.

Three, similar issues may be cropping up in Jammu, where Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar are being hosted, and in parts of West Bengal and Bihar, where Bangladeshis are quietly settling. The case for extending the NRC process to other states is beginning to be compelling.

However, this is where we come to practical politics. It is simply impossible to believe that millions of illegals – even if restricted to just Muslims – will be accepted back by Bangladesh. Moreover, by merely implying that so many people may face deportation, we are asking for communal trouble here.

The practical way forward must thus be three-fold.

First, assure all illegals that they can remain residents, and continue doing what they were always doing, in the foreseeable future. The only penalty will be that they will be struck off electoral rolls for 10 years, after which they can be given citizenship on the basis of naturalisation calculated from the date of detection of their illegal status. This offer can be conditional on good behaviour.

Second, the Citizenship Act 2016 amendments should be focused on separating economic refugees from political ones, especially persecuted minorities in three neighbouring countries. To the list of Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and Christian we can add Shias and Ahmaddiyas from Pakistan. These groups should be given priority for citizenship. Stricter norms need to apply to the rest.

Third, we must build more impermeable border fences, and do a deal with Bangladesh to take back at least some of its illegals. If needed, we should offer cash to rehabilitate those opting to return voluntarily, and willing to remain there, and this must be verifiable. In the past, those who were deported simply came back through our porous borders.

Assam’s problem is not Assam’s alone. It is a national problem. We need to treat it as such with a sensible policy that should focus on sending back some illegals, while also absorbing the bulk of them with temporary work permits, which can be converted to citizenship and permanent residency over time.