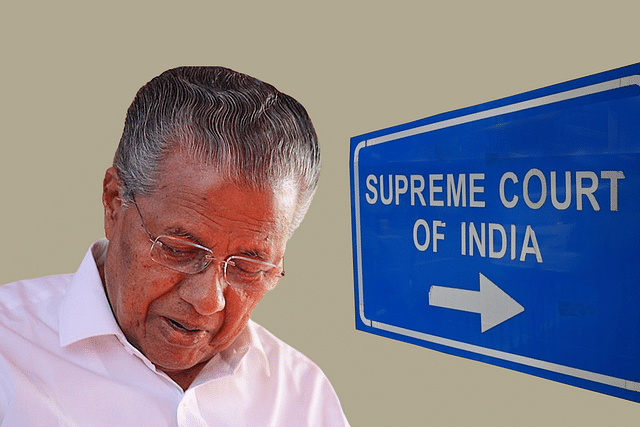

Can Kerala Government Invoke Article 131 To Move The SC Against CAA? What The Constitution Says

The State government has to establish its legal right which is likely to be infringed upon by the Citizenship Amendment Act so as to invoke Article 131 of Constitution.

Recently, the Kerala government moved the apex court under Article 131 of the Constitution, the provision under which the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction to deal with a dispute between the Government of India and one or more States. The other non-BJP ruling States have also taken a similar stand.

Article 13 of the Constitution of India contains an inclusive definition of “law”. One of the major legal sources is ‘enacted law’.

Article 246 confers exclusive power to make laws with respect to any of the matters enumerated in list One in the seventh schedule. Entry seventeen (17) of list I pertains to citizenship, naturalisation and aliens.

Article 246 (2) confers power upon Parliament and also State legislatures to make laws with respect to any of the matters enumerated in list III.

Article 246(3) confers power on the legislature of the States to make laws in respect of any matters enumerated in list II of the seventh schedule only.

And, therefore, a State cannot make any legislation in respect of the matters enumerated in list I of the seventh schedule.

The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, is a legislation made by the Parliament and therefore a “law in force”.

The CAA has been already challenged before the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Constitution. Now, the Government of Kerala has filed a suit invoking Article 131 of the Constitution.

In this context now, it is necessary to examine the scope and ambit of Article 131 of the Constitution.

A reading of Article 131 shows that the apex court has got original jurisdiction in any dispute between the Government of India and one or more States, if and in so far as the dispute involves any question (whether of law or fact) on which the existence or extent of legal right depends.

A plain reading of the Article shows that the dispute should involve an infringement of legal right of the State government.

Legal right means a right derived from a statute or the Constitution. Therefore, primarily, the State government has to establish its legal right, which is likely to be infringed upon by the Citizenship Amendment Act, so as to invoke Article 131 of Constitution.

The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, was duly enacted by Parliament by virtue of its power under Article 246(1) of the Constitution.

The State legislatures do not have any power to make any legislation in respect of “citizenship” and, therefore, the cannot claim infringement of such non-existent rights. In short, the States cannot refuse to implement the said Act.

Article 256 of the Constitution mandates that the executive power of every State shall be exercised so as to ensure compliance with the laws made by Parliament and any existing laws which apply in that State and the executive power of the Union shall extend to the giving of such directions to a State as may appear to the Government of India to be necessary for that purpose.

The State government does not have any power to make any legislation relating to Citizenship, and the same is within the exclusive domain of the Centre. Any law that is made by the Centre has to be implemented, since it is a constitutional mandate.

In order to invoke Article 131 of the Constitution, the State has to invariably establish either a legal right or a Constitutional right.

Article 256 mandates compliance of the Central legislation and, therefore, there is no constitutional right available to the State to invoke Article 131 of the constitution and filing of a suit under Article 131 may also amount to violation of Article 256 of the Constitution.

The Citizen Amendment Act does not violate any legal right vis-a-vis the State so as to enable the State to approach the Supreme Court under Article 131 of the Constitution.

It is only the individuals who may be affected by the legislation, and the recourse would be to challenge the same under Article 32 of the Constitution, which, in fact, has been done.

The apex court in State of Karnataka Vs. Union of India had an occasion to examine the scope and amplitude of Article 131 of the Constitution and held that the sole condition which was required to be satisfied for invoking the original jurisdiction of the apex court was that the dispute between the parties must involve a question on which the existence or the extent of legal right depends.

In the said case, the main line of argument was that the State would have locus to challenge the unconstitutional exercise of power by the Central government which encroaches upon States’ exclusive sphere in relation to the conduct of its Council of Ministers.

It could challenge the impugned action of the Central government because it prevents the State from exercising its power of direct inquiry into matters specified in the notification issued by the Central government.

There was a nexus between the Act of the Central government and the grievance of the State. The apex court also held that the words contained in the said Article clearly indicate that the dispute must be one affecting the existence or the extent of legal right and not a dispute on the political plane.

In the State of M.P. Vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court held that the only recourse to question the vires of enactment is only by challenging the same under Article 226 or 32 of the Constitution.

In the said case, Madhya Pradesh had challenged the notifications/orders issued under the provisions of Madhya Pradesh Reorganization Act by filing an original suit before the apex court under Article 131 of the Constitution of India.

In this case also, there was a nexus between the grievance of the State and the notification/orders.

In a recent judgment on the State of Jharkhand Vs. State of Bihar, the issue was referred to a larger bench and the same is pending.

In the said case, the rights under the Reorganization Act were affected and, therefore, certain provisions of the Reorganization were challenged.

In the State of West Bengal Vs. Union of India, the issue was with regard to Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition & Development) Act.

However, in all these cases, the respective States which had invoked Article 131 of the Constitution had certain grievances vis-a-vis the legislation/orders and their legal rights under a statute were alleged to have been infringed.

But presently, the States do not have any legal right derived from any statue or the Constitution of India so as to challenge the constitutional validity of the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 under Article 131 of the Constitution.

A State’s legal right is not infringed in any manner by implementation of the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019. The above referred cases stand on a different footing than the present case.