It Wasn’t Easy Being Bhai Parmanand

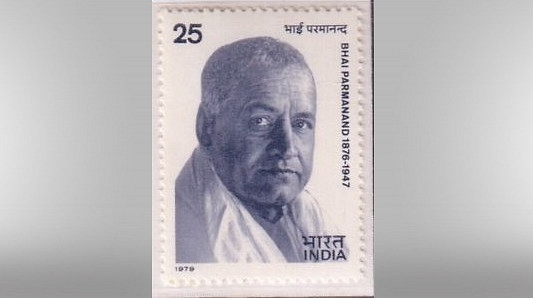

November 4 was the birth anniversary of one of the great minds of 20th century India, Bhai Parmanand. Here is Aravindan Neelakandan’s tribute to one of the many neglected Indian legends.

“The room was of the smallest dimension - cold and dark. It seemed to be her only home. It was indescribably poor, and she herself was nursing on her lap her sick child, while the elder child was sitting by the mother, wan, listless and pale. The child in the mother's lap had fever, and the mother herself told me how her eldest child had died of this only six months ago. It was easy to see from the dark ill-ventilated room and the poverty stricken condition of the family, how the eldest daughter had caught the disease.”

Gandhi’s colleague Rev. C.F.Andrews wrote this eye witness description of Bhai Paramanand’s wife. At that time Bhai Paramanand’s was in Andaman jail suffering ‘transportation with forfeiture’. The ‘forfeiture’ had deprived his family of even the cooking utensils and now his wife was supporting the family with a ‘scanty pay’ as Andrews put it, from her work as a teacher in an Arya Samaj primary school teacher.

Earlier Bhai Paramanand worked as lecturer of history and political economics, a life-member with a vow to teach at a fixed allowance (Rs. 75/-) and declined a higher career from Punjab University as it would have raised his salary above the limit of his vow. He had worked as Vedic missionary in South Africa. He had later gone to United States to coordinate the overseas attempts by Indians to achieve independence. Here he was active in the Ghadar movement. His cousin Bhai Balmukund came in the line of Bhai Matidas, the disciple of Guru Tegh Bahadur, who was martyred by Aurangazeb. And he was hanged to death and his young and beautiful wife Smt. Ram Rakhi, married only for a year, ended her life.

Bhai Paramanand was deported to Andaman. Here he, along with other convicts, had to extract fine coconut fibre from the bundle of coconut fibre given to them. They had to grind oil in the mill tied to the yoke like draught animals. British used Tandeels (convicts given black uniforms) to harass the convicts particularly the political prisoners. There were beatings and abuses from these guys. Rev. C.F.Andrews learning about the plight of Bhai Paramanand wrote:

The thought has come home to me again and again … how futile, how stupid, how insensate it is to keep one of the brightest and keenest intellects in modern India, a man with such noble qualities of mind and heart, imprisoned along with the lowest criminals for the rest of his life and engaged in the useless, senseless and meaningless occupation of grinding hour after hour at the mill.

Solitary confinement, restriction of movement by using iron-stake between the legs, hand-cuffs between the wrists and hand-cuffing behind the back, whipping with a maximum of thirty lashes… the prisoners had to endure all these tortures. Often the prisoners became suicidal. Bhai Paramanand records:

For the future-blank despair, for the present, the severity of punishment and of hard labour; under such conditions many prisoners become indifferent to life and resolve to destroy themselves. Though there is a search every evening and the warder keeps going round the lines at night with lamp in hand, they manage to conceal a piece of rope or improvise one by tearing to pieces their shirt or breeches and hang themselves to death. … Several such cases occurred during my stay there and these served to impress firmly on our minds how near the life and death was our place of residence.

Suicidal thoughts and a complete sense of purposelessness in rotting away entire life in the sub-human conditions in the prison started taking its toll on him.

My own mind was kept agitated by the thought, ‘Why should I live longer?’ A sort of special feeling of uneasiness occupied my heart. Every moment I was debating within myself whether I should cut shot my life or continue to live.

As Bhai Paramanand toiled in prison, the First World War was coming to a close. His observations regarding the war show a very humanistic and Indic vision. He saw the war rooted in ‘the very essence of European civilization, whose one ideal has been self-aggrandisement, by whatever means, at the expense of others.’ Unlike some other nationalists he did not harbor the notion that had Germany won the war India would have become liberated. He observed with cold and remarkable objectivity thus:

As regards the English nation, although it has kept us down and trampled on our rights, I had little hope that the atrocities would be less of the Germans came. No doubt, if both powers should fight in India, there might be a chance of improving our position.

If Indian political prisoners had any hope that with the end of the War the government would release them, they were smashed with the behavior of the government which enacted the Rowlatt Committee. Meanwhile, Chief Commissioner of Andaman at that time was one Col.Douglas who happened to be a great friend of Sir Michael O’Dwyer. One day he came to Bhai Paramanand and informed him that O’Dwyer still remembered him and asked if he was still alive. Meanwhile some of the letters of Bhai Paramanand which described the sordid conditions of Andaman got published in Punjab Tribune. This led to the solitary confinement of Bhai Paramanand. At this point Bhai Paramanand started a fast unto death. After a week the authorities started force-feeding him. The doctor who came to see the prisoner came with a tube for forcing the milk into the stomach through the nose. Bhai Paramanand writes:

Hands and feet were held tight and a long rubber tube was introduced through the nose into the stomach through which the milk was passed down. The process was painful but this is the usual thing in jail and was done by force.

The struggle went on for eight weeks. And after much persuasion by a new Superintendent who took an admiration for Bhai Paramanand he gave up the hunger strike that nearly killed him. In 1920 after five years he was released. Returning back home he found it hard to get a job and made peace with the idea that his wife would work in the school and he would look after the house. Some friends sent him to Kashmir in 1930 to regain his health. There he observed, ‘Yes, great injustice had everywhere been done to Hindus in respect to their religion, but such treatment had exceeded all the limits in Kashmir.’ The sight of Kashmiri Hindu women and children with the vermillion on their forehead and religious marks, made him ‘unconsciously bow’ his head remembering the ‘great sacrifice made by Guru Tegh Bahadur’.

Soon he took up the work that was dearer to his heart - teaching. He wanted to create an educational system that was completely Indic. So when Gandhiji started his national educational programme, ‘Bhaiji’ as he was called, gave his full cooperation. When he started again in the college one of the students who enrolled received his particular attention. He was Bhagat Singh.

Bhai Paramanand had a great respect for Gandhi but he was highly critical of the Khilafat movement which he rightly recognized as having ‘fanned bigotry and fanaticism in the minds of the Muslims.’ Attacks on Hindus had already started taking place throughout the country: Malabar, Multan, Kohat, Calcutta etc. At Saharanpur, where he went personally for relief work, he saw the utterly helpless plight of Hindus and discovered that the local Khilafat committee leaders were the ones indulging in the riots. When eminent Hindu leaders of the Congress like Swami Shardanand, Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya and Lala Lajpat Rao realized the danger the Hindu society was facing and started a movement for Hindu sanghathan, Bhai Paramanand also joined the movement. The communal award system with which the British were playing havoc with social harmony and to which the Congress had largely compromised, pained the visionary in him. He stated that if the communal award remains the way to Swaraj would be closed for Hindus forever and that they would be subjected to double slavery.

When Congress leaders started attacking him that he was being afraid he remarked caustically that he knew no fear even when imprisonment was dreadful, so why he should be afraid ‘of going to jail now when even such persons as have passed all their lives in wine and women could court two or three months’ imprisonment and come to be known as fearless or brave patriots.’ For the Congressmen it would not have been lost upon them as to whom he targeted. Though a great admirer of Gandhiji he never lost truth in awe of the Mahatma. He rejected the idea that it was Gandhi who made Congress and national struggle a people’s movement. Given the fact that even today this idea that Gandhi made the independence movement a mass movement prevails, the observations of Bhai Paramanand need to be quoted at length:

Very often I am told that the Congress, in spite of all its defects, has at least done one great good to India. It has brought awakening in the land. … If Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress did anything it was this: they harnessed that universal sentiment to the service of their own movement.

Bhai Paramanand was also a caste abolitionist and started the Caste-Elimination movement within Arya Samaj. He also adapted a child from another community as his own son and brought him up. Like M.C.Rajah of Tamil Nadu, he also held that before Hindu-Muslim unity first Hindu unity should be achieved. In 1932, a tragedy struck him in the form of death of his wife who had given him constant support in all his struggles. In 1939, his youngest daughter died, too.

When at last in 1947 the freedom came with the vivisection of India, Bhai Paramanand saw Hindus becoming refugees in their own land over a single night. He had long ago proposed a phased regrouping of people. Had it been listened to, much human tragedy and suffering could have been averted. Yet he saw an independent India and he died on 8 December 1947.

Yesterday was his 140th birth anniversary.

[All quotes and data taken from ‘The Story of My Life’ by Bhai Paramanand, Ocean Books, 2010)