For The Sake Of Judiciary, A Mechanism To Judge Judges Is A Must

Impeachments are too drastic, and cumbersome as well. There has to be another way to ensure accountability of judges.

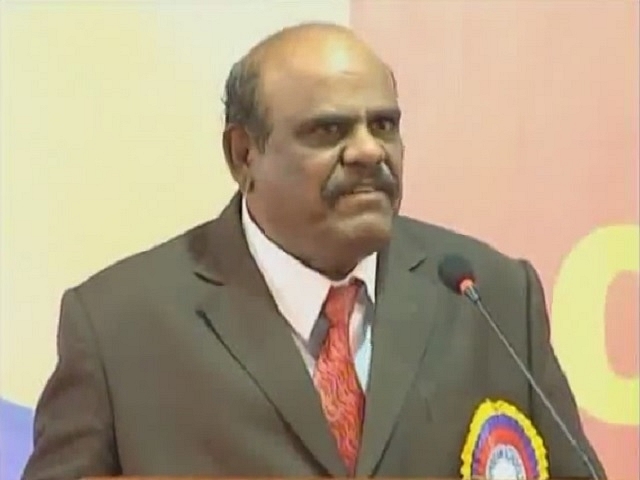

In response to a bailable warrant issued and duly served for the appearance of Justice C S Karnan - puisne judge of the Calcutta High Court – the learned judge made his appearance on 31 March, 2017 before the Supreme Court with defiance in the air and his personal representation.

Unprovoked, the seven-judge bench granted four weeks time to Justice Karnan to answer the charge of contempt over his allegations of corrupt practices by judges of high courts and the Supreme Court. Pending this hearing before the top court, the learned judge issued an order India has never witnessed before. In that order, he asked Chief Justice of India J S Khehar and six other judges of the apex court to appear before him at his New Town residence by 24 April 2017, for violating his rights as a Dalit and humiliating him in public. The order called the seven Supreme Court judges “national offenders” and said they had shown caste prejudice against him and insulted him on 31 March by probing about his mental health. “Hence all the seven judges are offenders under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes Atrocities Act,” said the nine-page signed order. “The Hon’ble judges will appear before me at my Rosedale Residential Court and give me their views on the quantum of punishment for the violation…” said the order.

Why have matters come to such a pass? Is this is an aberration that we may never get to see again from a judge of the higher echelons of the judiciary? Have we seen the nadir or is it only the tip of the iceberg? Where are we headed, with judiciary, the third pillar of a democracy, overreaching beyond its contours and the other two pillars, the legislature and executive, thoughtlessly offering space with dent on their moral compasses?

The Supreme Court may be standing tall with seven upright judges on the bench, for the present. But is it not a testimony to a fall in the standards of judiciary that they have been forced to initiate such suo motu proceedings to discipline one of their own? Is it not a poor commentary on the absence of a mechanism to judge judges since impeachment as the only route is not a realistic one and its invocation may add more ignominy on the institution than could be bargained for? Is it not, above all, a reflection of the opaque ways of the collegium which was responsible for placing such nominees on the bench? All poignant and pregnant questions with no easy answers.

It was in October 2015 that the Supreme Court struck down the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act (NJAC). The proceedings were animated and acrimonious and the Attorney General Mukul Rohtagi launched a no holds barred attack on the appointments by the collegium to drive home the point that the system put in place by judicial law making was opaque’ and uninspiring and it was time for the judiciary to yield to the unanimity expressed in the constitutional wisdom expressed by both Houses of Parliament and required number of State legislatures.

In particular, the government told the Supreme Court that the collegium had recommended and reiterated the appointments of certain persons as judges despite adverse Intelligence Bureau reports and “severe” comments by its own judges questioning their ability and integrity in some cases. Mukul Rohatgi had submitted to the court a list of names running into 10 pages with comments from the Intelligence Bureau, the government and the apex court judges, to demonstrate that when the collegium insisted on such recommendations, the government was bound to accept them. He had pointedly highlighted that ‘several bad apples’ had slipped through.

The Supreme Court was not convinced. It chose to strike down the constitutional amendment - a rare phenomenon - on the premise that the presence of the Union Law Minister on the selection panel made inroads into the basic structure of the Constitute viz. inalienable right of citizens to an independent judiciary.

But the 4:1 verdict was not immune to the criticism on the ‘functioning of the Collegium as a secret chamber to elect themselves’ and Ruma Pal’s famous quote: “Collegium affairs were the best kept secret in the world” hit the credibility of the institution that was conjured out of thin air without a constitutional basis. And Justice J Chelameshwar’s dissent flagged off serious concerns over the isolationist practices over the executive. Yielding to its wounded instincts, the Supreme Court then promised a ‘consensual Memorandum of Procedure (MOP) for the appointments’ with the executive. It was a thin wedge but the Union of India had nothing else to say, merely insisting on having its say over the MOP.

After a back and forth journey for over a year, under the present CJI, the collegium has fallen in line with the executive’s ‘insistence’ and the MOP has now been ‘finalised’ and sent to the executive for implementation. Both the executive and judiciary have magnanimously sorted out the ‘serious differences between them on the MOP for healthy functioning of the institution/s”. In the wake of this welcome development, we hear, “In a record of sorts, a collegium headed by J S Khehar has cleared the names of 51 judges for appointment to 10 high courts across the country” on 15 April 2017. But what of the nominees?

Well, it is now given that we have a regime of the collegium holding sway - despite Finance Minister Arun Jaitley calling it an unelected tyranny’ when the NJAC was struck down. The political cleavage is showing too wide, and there is no way the collegium is going to go away for now. It is here to stay. It is in this scenario the present unsavoury episode of a sitting judge of a High Court being arrayed to face contempt proceedings has to be posited to see what lessons the institutions have learnt or ought to learn.

First and foremost – it is now time to have a mechanism to judge judges. For too long we have gone without judges accountability being institutionally tested, for fear of treading on the independence of the judiciary. Impeachment proceedings are esoteric and on the odd occasions it has been tapped into - it has proved to be a non starter or a half-finisher. The process is so cumbersome, lending total immunity to the incumbent to not dread the prospect at all.

Most importantly, however, the collegium affairs need to come out in the open. The Supreme Court should not fight shy of embracing even the RTI (Right to Information) option. Opacity is enemy of the people. If the 51 names recommended in a ‘record of sorts’ are not to include difficult customers, we the people, not necessarily the executive alone, need to know as well on what went into their ‘picking’.