Migrant Crisis Tells Us We Don’t Know Enough About Labour, Migration Patterns; Every State Needs To Build A UP-Like Database

It is a matter of shame that we are unaware of the scope of our biggest strength — labour resource — in the 21st century.

Does it need a Coronavirus pandemic to get our house in order and develop a database of migrant workers?

The answer is a ‘yes’.

Migrant labour — this phrase has been the most heard, dreaded, exploited, and debated in the country — only second to ‘Coronavirus’.

But while a vaccine to the latter may eventually be found, if the former doesn’t receive the attention it should, given the scale of its impact highlighted by the pandemic, it can hold the country’s economic progress to ransom forever.

As the Supreme Court heard a suo motu case regarding the migrant crisis that followed the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown, various threads of what ails this ‘resource’ — so far not found worthy of consideration by the authorities — have emerged and need constructive analysis and action.

Solicitor-General Tushar Mehta, who briefed the court about steps taken by the Centre to avert the migrant crisis, unveiled the scale of the issue, and the numbers are just the tip of the iceberg.

Justice Ashok Bhushan, who leads the three-member bench hearing the case at the very outset said, “We are not disputing the fact that the Centre has not taken steps. But whoever needs help is not getting that help. States are not doing their bit,” as reported.

Why? Because states sure have no data. There are numbers of in-migrants and out-migrants floating around, but there is no database of inter-state migrants in the country.

And since they are nobody’s votebank, no one cared for them either, unless, of course, one needs them to ensure fake votes, for which there are enough means already in place.

The numbers that Solicitor-General Mehta revealed, as he represented the Centre and clarified on the efforts taken for the migrants, tell a tale of unchecked ‘growth’ of certain cities, absolute neglect of ‘development by many states that swear by socialism and the need to now organise the unorganised sector.

In Mangaluru, we had umpteen instances of migrant labour ‘emerging’ from tiny suburban or semi-rural pockets of the district — pockets that have neither large infrastructure, nor major industry nor large expanse of agriculture.

For a city whose population itself is five lakh and hasn’t seen any massive investment other than real estate in the last two to three decades, the number of workers who registered on the Seva Sindhu app to head ‘home’ to Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Bihar is eye-opening.

When the first set of trains was arranged here, a total of 20,000 workers from Jharkhand, UP, and Bihar mainly had registered and many of them landed at the railway station even before the arrangements could be put in place.

The Seva Sindhu app did try and bring a semblance of sanity to this whole effort of reverse migration, but it addressed just their travel needs at this hour of crisis.

While the district administration was trying to pacify the crowd and asking them to not gather until informed, the Opposition leaders were inciting them, adding to their woes.

Irony died a rude death every time ‘heart-wrenching’ images were flashed across media.

Definitely not belittling their pain, the fact that those who have been in power for decades but aren’t any longer, are crying fowl at this hour, only speaks volumes of how the nation has failed to address its largest resource.

Certain states have not been responding to requests to start trains — to even take its own people back.

West Bengal has been reluctant way before cyclone Amphan hit it and is now conveniently using the cyclone as an excuse for its unwelcoming inaction.

Uttar Pradesh accounts for the highest in-migrant and out-migrant rates in the country and has hence, stayed in the news every single day.

It has the greatest load of handling the migrant issue this pandemic season, but thankfully, it also has a Chief Minister whose proactive handling of this issue can be emulated across the country.

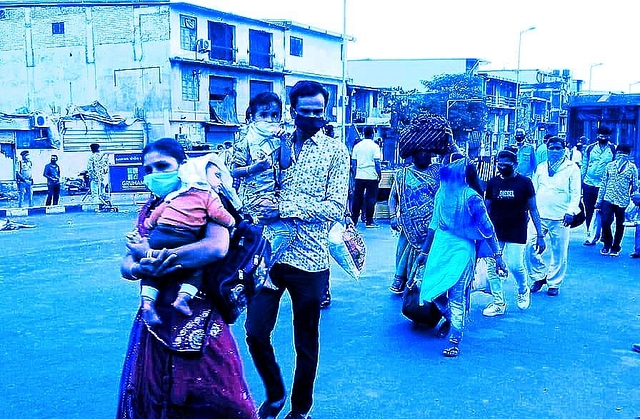

The images are hurtful, their plight unimaginable as rumours — both intentional and unintentional — have left them ‘stranded’ either on roads, at railway stations or in no-man’s land.

But all this could have been avoided if only the states knew where, why and how many of their domiciles ‘migrate’ within the country.

While international reverse migration has been considerably better handled, the cluelessness of the governments of the scale of the problem is what has turned an essentially seasonal affair into a nightmare.

The number of people moved so far by these 3,700 Shramik Special trains is higher than the population of New Zealand, whose leadership is being hailed by certain intellectuals in this country.

As many as 50 lakh people alone have been transported back to their hometowns by train between May 1 and May 27.

As many as 41 lakh migrants have moved by road using government transport as a means, as they belong to neighbouring states.

And hence, the first thing the states need to do is to create a database of migrants of every other state.

Along with skill mapping and profiling of the migrants, like has been done in Uttar Pradesh, the nation now needs to set in place an aadhaar-linked database that is mutually shared between states and monitored by a central body.

While this can enable tracking in times of crisis like the current one, it can serve as a resource register for training, skill development and social benefit provisions.

A database that is linked to a registered mobile number (it isn’t a luxury anymore) would ensure only official information is passed on to these migrants in an hour of crisis like the current one.

Every state would have an entire list of its ‘own people’ and their current location as updated annually, and can also serve as a tool to highlight exploitation by employers.

This would surely save us the garbed activism of those who have not failed to make photo-ops of miseries or use their woes to further their agenda.

The database can be used to reach out to these workers under the Skill India programme, and can also strengthen the rebuilding of the economy.

It can also prove to be a feeder resource to rural and semi-rural startups in a bid to revive the suburban economy.

And if India truly aims to lure investment and companies that are leaving China, then channeling, categorising, skilling, upskilling and reskilling its biggest resource — labour — is indispensable.

This crisis is the perfect opportunity.