Poor Economics Is At Heart Of Rahul Gandhi’s NYAY. How Much Does Abhijit Banerjee Plead Guilty To?

NYAY may be 12 times more generous but its real problem is poor economics.

Unlike MGNREGA and Kisan Samman, NYAY with its targeted approach would have been a nightmare to implement.

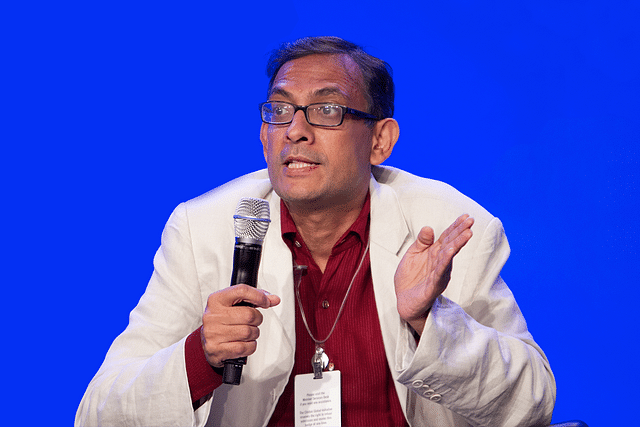

One wonders how much of the blame for the Congress party’s NYAY scheme (Nyuntam Aay Yojana) should be laid at the door of Abhijit Banerjee, joint winner of the Nobel prize in economics this year along with Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer, but at least some of it will surely stick to him.

Soon after the Nobel award for Banerjee & Co was announced, Rahul Gandhi tweeted his congratulations, and claimed Banerjee’s concurrence for NYAY. Gandhi tweeted: “Abhijit helped conceptualise NYAY that had the power to destroy poverty and boost the Indian economy. Instead we now have Modinomics, that's destroying the economy and boosting poverty.”

Under the poorly-thought-out scheme, 20 per cent of the poorest households in the country were to be given Rs 6,000 a month – Rs 72,000 annually – at a final cost of Rs 3.6 lakh crore annually when fully rolled out. Luckily for the economy, Rahul Gandhi did not come to power in May 2019.

The real problems with the scheme were how the government would go about selecting this 20 per cent, and how the scheme would be financed. As a targeted basic income scheme for the poor, the scheme was likely to have faced as many implementation hurdles as any other, thus leading to leakages and corruption.

In contrast, consider how simple the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi is: it covers all farming households, and offers a manageable income support of Rs 6,000 annually, paid out in four-monthly instalments of Rs 2,000 each. This yields an average of Rs 500 per month. It is thus a universal farm income support scheme. Though initially targeted at small and marginal farmers, post-election the scheme was rolled out to all farming households, big or small.

While one can claim that the Rahul Gandhi scheme is 12 times more generous, and hence more capable of wiping out acute poverty over five years, the real problem with the scheme is its addressability and poor economics.

Unlike MGNREGA, which was universal and thus self-selecting, or even Kisan Samman, which is applicable to all farming households, NYAY with its targeted approach would have been a nightmare to implement.

On the other hand, flexibility and self-selection is in-built into Kisan Samman.

One could argue that Rs 500 per month is too little, and also that some of it may go to rich farmers who don’t need the additional income. But consider the next step: if another Rs 6,000 is paid out while eliminating the fertiliser subsidy, this time the benefit would go more to small and marginal farmers, who spend less on fertilisers than larger farmers, and can thus use the savings for other expenses.

Logically, PM Kisan Samman can be rolled out to become as large as NYAY but with fewer hiccups while identifying the beneficiaries. At some point, it could have been extended even to urban areas, by offering it as a cash replacement for food subsidies.

Abhijit Banerjee’s book Poor Economics, jointly authored with spouse Duflo, showed what kind of schemes work best for the poor. He would probably not have allowed a scheme like NYAY to meander into a mess if he had had the actual responsibility for its implementation if the Congress party came to power.

But at the macro level, his economics does not seem too different from traditional Keynesian remedies, for he advocated raising taxes or increasing deficit financing to finance NYAY. High government borrowings would have ultimately resulted in an 'inflation tax', and Banerjee seemed okay with that.

That, surely, is poor economics.