Ram Mohan Roy And One-Way Time Travel

George Orwell once said that if you want to destroy people, you have to deny and obliterate their own understanding of history.

It is bad enough when your enemies do it to you. Losing your sense of history to friendly fire is a tragedy of nearly Greek proportions.

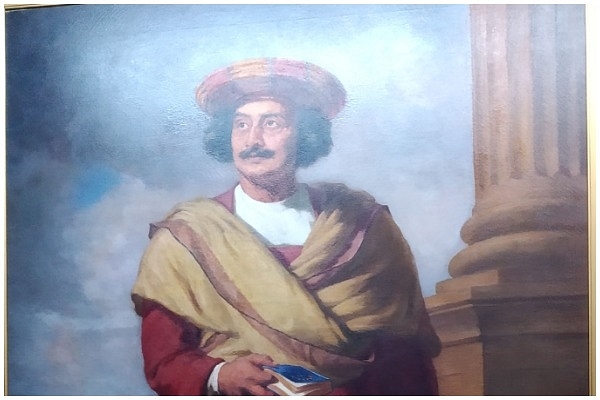

In the 1953 film The Wild One, Peggy Maley’s Mildred asks Marlon Brando’s Johnny “Hey, Johnny what are you rebelling against?” The insolent Johhny responds “What’ve you got?” I was reminded of this as a heated debate erupted over the role of 19th century Bengal reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy in ending the practice of sati. Former Bollywood starlet Payal Rohtagi, of all people, fired the first round calling Roy a traitor and a British chamcha. Soon writer and intellectual Rajiv Malhotra and a popular anonymous twitter handle supported Rohatgi’s position. When writers Hindol Sengupta and Sanjeev Sanyal responded with what they thought was a more balanced version of the events, the other side saw it as a parochial attempt to defend Roy solely based on his Bengali identity. Later, portal Sirfnews published a fairly detailed rebuttal to Malhotra’s charges against Roy.

At this point, it is up to the individual to go through these arguments and make up their mind. The intention of this piece is to examine the larger trend of judging historical figures based on today’s standards, a practice founded and popularized by reactionary left, but now finding surprising traction with the reactionary right. A couple of points before we get to it though.

Firstly, we need to understand that the very nature of social media promotes us versus them, black or white type of binaries. Unfortunately, likes of Rohatgi have mastered this art. Therefore, it is all the more important to be aware that almost nothing in history is in black and white and you can never replace context with multiple choice, like Malhotra tried to do here. If devil is in details then the God of history resides within nuance. Unfortunately in the age of social media, nuance has at once become an endangered species as well as the public enemy number one.

Second is about the state versus nation rhetoric. Malhotra ran poll asking if Rashtra came first or regional identity. Nearly all the people who speak about putting nation before state are never speaking about their own state. The state identity is an integral part of our value-system. I am yet to meet an Indian who loathes his state but loves his nation. Asking someone to choose one over the other is effectively asking them to give up a part of their identity as a test of patriotism. If abandoning your state identity can be made a test of your national identity, then similarly, abandoning your national identity can be made into a test of your global identity. The way to steer clear of this is by acknowledging the essentially interlinked, integral nature of state-nation identity instead of asking people to choose one over the other.

But that still leaves the core question- Is it fair to judge historical figures on the basis of yardsticks and knowledge rooted in present age? Can Roy be judged based on the history that unfolded after his time? Should he be expected to have foreknowledge of the enormity of the challenges posed by proselytizing evangelicals? And finally, does the trade-off between his goal and his methods make him insufficiently pure?

In this must read piece, Brian Morton discusses similar dilemma facing literature students. How does a student of literature reconciles with sexism, class snobbery, racism and anti-Semitism of great authors from the bygone era? Is consigning these greats to trash bins the only honourable way out? Morton’s response is based on two premises.

First, to judge writers from the past based on today’s values is effectively imagining the book to be a time machine that brings the writer to present. Morton argues that it is not the writer who is travelling in time, it is us the readers, who through the books, who travel to a time that was different in nearly everything from ours. This slight adjustment in attitude might help us have a different kind of experience. Second, and equally important, is that whenever we bring figures from past in our times, we are indirectly reinforcing our complacence, as if the moral improvements sought by generations have reached attainment with ours. A casual look at the wrongs persisting in the society today, would show that is far from the case. The reverse, i.e. us travelling in the past- doesn’t carry the same implication.

If we apply the same standards to Roy’s case, we will see a time when the brutal Mughal rule was just over and many people in the area considered the British as saviours (they would be proven wrong but that was still in the future back then). If we consider the choices he made based on the circumstances as well as information available at that time, we can view his actions with definitely a less judgemental perspective. I had written about the futility of analysing hard decisions without understanding the role of history itself while reviewing Hindol Sengupta’s biography of Sardar Patel. Compromises are a hallmark of people with skin in the game. Perfect purity is the luxury of armchair analysts who never put anything on the line.

But does it mean figures from past are not open to criticism? The reactionary right asks. Of course, they are. However calling someone a missionary stooge or British chamcha hardly falls into the category of valid criticism. At the very least, the anti-Roy lobby is guilty of poor choice of words. Has calling Roy a British stooge made the Indian or the Hindu discourse stronger? Has mitigating the sati custom made us closer to achieving cultural nirvana? And finally, has this drama earned the lead actors a little bit of additional following?

Can we talk people? We must stop making cynicism sound revolutionary. Like a stopped clock that is right twice a day, a cynic often proves himself right by doubting everyone. To that extent it is the path of least resistance. Its effect, however, is devastating. What began as an earnest attempt to challenge the left dominated discourse is quickly denigrating into moral and intellectual scorched earth. This needs to stop. We have to once again start defining heroism in terms of courage to act, rather than compulsively looking under every fingernail for dirt.

Like a magnifying glass that can be used to see small objects better or to set them on fire, we can use our knowledge of history either to understand the context to actions of men like Roy or to use it to gaslight them. George Orwell once said that if you want to destroy people, you have to deny and obliterate their own understanding of history. It is bad enough when your enemies do it to you. Losing your sense of history to friendly fire is a tragedy of nearly Greek proportions.