Twitter Vs Free Speech: 1st Amendment To US Constitution Is Becoming A Farce

The US first amendment is quirky because while it disables the government from messing around with free speech or religious freedom, it does not prevent private individuals or companies from doing so.

When it comes to making sense of the US Constitution, especially its free speech rights, the same words can mean different things to different people.

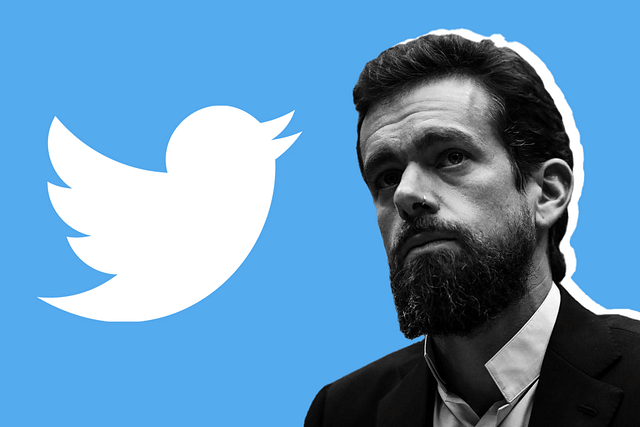

On Monday (8 March), micro-blogging site Twitter, which has been a law unto itself in deciding who to ban and who not to, sued the Texas Attorney General for curbing its ‘free speech’ rights which are guaranteed by the first amendment to the Constitution.

Apparently, Twitter has not taken kindly to Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton for initiating a probe into its “content moderation” policies, which deplatformed a sitting president in January after Donald Trump allegedly incited a crowd of armed supporters to storm Capitol Hill.

Interestingly, both Paxton and Twitter claim they are acting to protect free speech.

While Paxton initiated an investigation into Twitter’s content moderation policies, which he said were “discriminatory” and “unprecedented” and intended to silence Conservative voices, Twitter claims that his demand for access to all emails and other communications related to content moderation amounted to retaliation against it for deplatforming Trump.

Twitter’s refusal to share details of its content moderation policies are apparently protected under the first amendment, which does not apply to private firms. They are free to censor to their heart’s content.

Let’s see what the US First amendment says:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

The operative part of the amendment for our discussion is the reference to disallowing Congress from making any law that will abridge “the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

Clearly, Twitter’s interpretation of this amendment is that while government cannot abridge free speech, Twitter, a private company following its own editorial policies, can.

The case against the Texas Attorney General, filed in a California Federal Court, will be interesting to watch for two reasons:

One, it will test once again whether the free speech rights guaranteed under the US Constitution can apply to private platforms or not. Granted, publications can exercise their own rights to publish something or not to; but can a platform which is not a publisher do so?

Two, the case will run parallel to other actions launched by various US states to curb the power of Big Tech. In December 2020, the US Federal Trade Commission and 48 attorneys-general of various states filed lawsuits against Facebook for its policies that allegedly kill off competition. Some 38 US states have also filed anti-trust lawsuits against Google for monopolising the Internet search market which hurts both consumers and advertisers.

The US first amendment is quirky because while it disables the government from messing around with free speech or religious freedom, it does not prevent private individuals or companies from doing so. And in a country where private enterprise and Big Tech are often more powerful than many states or the government, the free speech guaranteed to citizens is effectively nullified when powerful platforms exercise their own censorship rights on users.

The same applies to freedom of religion, again guaranteed under the same first amendment. The right allows companies to practise discrimination on grounds of religious conviction. This means that if a state allows gay marriages to be registered, an individual professing Christian ideals can refuse to practise it in his company or individual capacity. In other words, freedom of religion includes the right to practise bigotry.

On the other hand, Donald Trump’s alleged exhortation to his supporters could well fall foul of the Supreme Court’s own interpretation of free speech rights, including exhortations to violence that do not result in any immediate violence.

In Brandenburg Vs Ohio (395 US 444 - 1969), the US Supreme Court created a very high threshold for prosecuting people calling for violence.

In this case, a Ku Klux Klan man, Clarence Brandenburg, was convicted under an Ohio law which banned the advocacy of violence as a “duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform.”

The Supreme Court annulled the Ohio judgement, and its verdict has been summarised thus by one law website:

“Held: Since the statute, by its words and as applied, purports to punish mere advocacy and to forbid, on pain of criminal punishment, assembly with others merely to advocate the described type of action, it falls within the condemnation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments. Freedoms of speech and press do not permit a state to forbid advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” (Italics mine)

In short, advocacy of violence in principle is all right, but it is banned only if it is intended to produce “imminent lawless action”. One wonders how one can define “imminent lawless action”. Will it apply only if a speech gets a mob to turn violent immediately, and not if the same group bides its time and indulges in mayhem after a few days or months, or plans for it covertly?

The Brandenburg judgement, cited now in India after the government took action against some violent anti-CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act) agitators and the 26 January violence by one section of farmers, does not make sense even in the US context.

The truth is the US Constitution’s ideas on free speech and freedom of religion do not make sense in the modern context of big platforms acting arbitrarily to curb free speech, and entire ecosystems practising “cancel culture” in academic institutions, workplaces and media entities.

For India, the message is simple: let us not continue to assume that laws made in a specific US or European context are relevant to us. We have to evolve our own rational laws on free speech that call for moderation but not bans, and tolerance for a lot of diverse religious practices unless they seriously violate individual human rights.

Brandenburg is not a relevant context for us, where rallies and processions almost always result in violence or riots or destruction of property. We have to make laws to prevent violence that are relevant to our context without compromising free speech, freedom of conscience, and right to protest peacefully.