What CAA Means For Secularism and Citizen Rights

Secularism, at its essence, means a divorce of the state from religion as it views religious beliefs as a private affair.

The Citizen Amendment Act has nothing to do with secularism and it does not make religion a criterion for citizenship.

What is secularism — is it the protection of rights of individual minority groups or does it mean strengthening individual rights of citizens?

By strengthening the rights of every citizen, we restrict the chances of excesses, by an individual, by a state, institution or even by a community. This, in turn, automatically ensures that minorities are protected from religious persecution, from discrimination and from exploitation.

India should, therefore, strengthen the rights of every individual rather than try to specify a contract that focusses on allocation of specific rights in the form of an incomplete contract which becomes extremely difficult to enforce.

B. R. Ambedkar had raised important questions regarding the rights of minorities in Pakistan in The Partition of India as he attempted to discuss the question of population transfer.

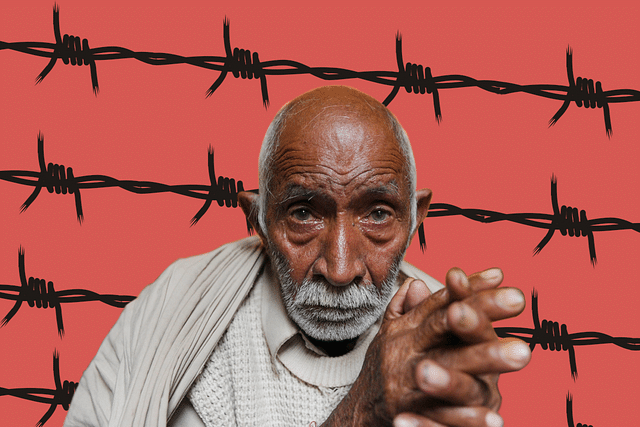

Nobody can deny that minorities have been persecuted by Pakistan. It is well regarded that the country did not legitimise marriages of Hindus till as late as 2017. The fact that such discrimination continued while we did not have a CAA reflects poorly on us as it illustrates our failure to keep our commitment to former subjects of the British Indian government.

The recent incidence at Kartarpur of kidnapping and forceful conversion of a Hindu girl reflects the extent of the weakness of rights in the State of Pakistan. The stunning silence by the Opposition, India’s media and even the minorities exposes the lack of empathy towards victims of religious persecution.

Partition, Secularism and the CAA – correction of a historical wrong

Many have forgotten the bloodshed that happened during the partition of 1947 which was a combination of political and religious interests culminating in the creation of a theocratic state of Pakistan.

In contrast, India adopted a more secular model of governance keeping in mind its rich cultural heritage. It must be noted that at the time of adoption of the Constitution and the Preamble, the words secular and socialist were not a part of the same.

Both, B R Ambedkar and Pt Jawaharlal Nehru were against the inclusion of both these words while acknowledging the need to have a state that does not have a state religion.

Therefore, they committed to the idea without explicitly using the term in the preamble and Ambedkar highlighted “what should be the policy of the State, how the Society should be organised in its social and economic side are matters which must be decided by the people themselves according to time and circumstances. It cannot be laid down in the Constitution itself because that is destroying democracy altogether.”

This statement is powerful, as it also highlights the problem associated with the specification or the use of the word socialism in the Constitution.

Secularism, at its essence, means a divorce of the state from religion as it views religious beliefs as a private affair. Consequently, there is no room for secularism and separate personal laws that have continued to exist in India. The concept of separate laws based on identity ignores the principle of Veil of Ignorance and might be against several interpretations of principles of Rawlsian justice.

The Citizen Amendment Act has nothing to do with secularism and it does not make religion a criterion for citizenship. The CAA merely provides a separate window for speedy citizenship to citizens that have faced religious persecution in the three countries of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh.

This means that Hindus, Christians, Parsis and all religious minorities in these three countries that have faced persecution will be granted citizenship. It is well regarded that they have indeed faced persecution and many of them are already in various parts of India without necessary rights.

To deny them of the same is only going to be morally incorrect and reflect the lack of empathy. To take it further, it would reverse the culture of India to accept people from across the world who have faced religious persecution.

The question of why not have Ahmadiyyas or Rohingyas been included in the Act is often raised by many, but they face sectarian persecution, and not religious persecution.

The present law is only concerned with religious persecution.

The logic behind a focus on religious persecution is that many families at the time of Partition could not come to India. That is, a complete transfer of population did not happen. Moreover, the assurance given to minorities in these countries regarding their rights were disregarded. This, in turn, makes it our moral duty to correct this historical wrong and it is a failure of our social conscience that this came so late.

(This is the second in a 3-part series on CAA. Read the first part here.)