Indian Economic Planning

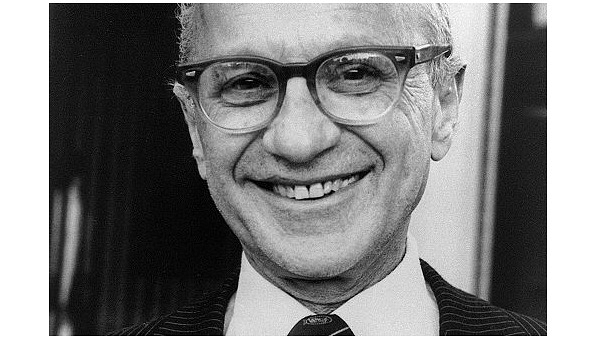

The below essay written was written by Milton Friedman after he had traveled extensively across India in 1963. The essay is striking in its prescience in predicting the future of the Nehruvian planned economy. Passages on the intellectual ossification of Indian economists (apart from a handful) and the quiet acquiescence of the vast majority of the intelligentsia are a timely reminder for the need to vigorously counter the Delhi establishment.

It is now well over a decade since India embarked on a policy of “planed economic development”. The U.S. government has strongly supported this policy, contributing a total of $4 billion in foreign aid through 1962. We have rightly regarded India as a key country in the struggle for the uncommitted nations of the world, as the major counterforce to the influence being exerted in the Far East by China. We have also rightly regarded the incredible poverty of millions as a challenge to the humanitarianism of the West. Unfortunately, Indian economic policy has not been producing the results that they and we hoped for and I do not believe it can do so. That was my tentative conclusion some eight years ago after a two months visit to India. It has been greatly strengthened by observations during a recent two months visit and particularly by a comparison of the situation then and now.

On the positive side, there are clear signs of improvement since my earlier visit. The roads in the countryside are notably better, there are many more bicycles and automobiles in both city and country, beggars, though still numerous, seem somewhat less ubiquitous. There are any new buildings, some striking, and more and better hotels; new industrial plants and few rapidly expanding centers of small industry; there are new Universities and evident signs of the expansions of old Universities. Much of this and more is to the good. But unfortunately, the progress appears spotty, and some of the appearance of progress is misleading. Many of the most impressive new structures are signs not of progress but of waste, for example, factories producing items at for higher cost than that at which they can be purchased abroad. Most important of all, there is little that is evident to the naked eye in the way of improvement in the conditions of the masses of the people. On every side, there are extremes of unrelieved poverty that it is difficult to make credible to someone who has not been to India. As a friend form Britain remarked after his first visit to Calcutta where over a tenth of the population have no home other than the street: “One can adjust to a square mile of this kind of thing but when it goes on for square mile after square mile, it is more than one can bear.” These conditions seem to have shown little if any change in the past decade.

This kind of casual impression is most untrustworthy, especially when it concerns conditions at a level of living which the observer has never come close to experiencing himself. What he poor in India might regard as a major improvement, you and I might not be able to recognize. However, much objective evidence confirms these general impressions.

One bit comes from work done for a committee appointed by the Prime Minister to study changes in the distribution of income. The chairman of the Committee, Prof. P.C. Mahalanobis, is director of the Indian institute of Statistics, a member of the Indian Planning Commission, the author of the draft framework of the second five-year plan, and one of the people who has done most to shape present Indian ideas of economic planning. The report of the Committee had not yet been made public when I was in India but Prof. Mahalanobis, in private conversation, showed me some of the work he and his associates at the Indian Statistical Institute had done for the Committee. Data from sample surveys of Indian rural and urban households indicate that the poorest third or so of the populations experienced no increase whatsoever in food consumption per capita during the decade for the 50’s – which roughly coincides with the first two five – year plans. And it must be recorded that food accounts for three-quarters or more of the total consumption expenditure of the poor.

Aggregate figures on the consumption of specific items support the general impression given by household surveys. The major items of consumption for the masses of India are food and cloth. The greater part of food consumption is accounted for by food grains rice, wheat, other cereals, and pulses. Indeed, at the bottom of the income scale, food grains along account for half or more of total expenditure on all items of consumption. Per capita availability of food grains has fluctuated a good deal but with no steady upward trend: it was about the same in 1958 as in 1950, in 1960 as in 1955. The situation is not much different for cloth. The number of yards of cloth per capita is now no higher than in 1939. [CORRECT? ] In the decade from 1950 to 1960, it has varied from in 19 to in 19. The consumption items that have shown the most rapid increases have been items like bicycles, sewing machines, automobiles-not luxuries by Western standards by clearly so by Indian standards.

The official estimates of national income – that favourite magnitude of modern growth-men -give only a slightly more favourable impression. National income, corrected for price change, rose during the decade of the first two five-year plans at the rate of about 3 ½ percent per year, but population rose at the rate of 2 per cent a year, so per capita output rose by about 1 1/2 per cent per year. And even these figures overstate the progress. In the first place, the official figures probably overstate the growth in output during the second five-year plan period because they make insufficient allowance of the price rise that occurred (this overstatement is almost surely much larger than the major error in the opposite direction, which is underestimation of the growth in the output of small-scale industry). In the second place, an increasing fraction of national income has taken the form of capital investment and government expenditures. The new and elaborate office buildings in New Delhi, the elaborate luxury Ashoka hotel built by the government in New Delhi,the strikingly well-appointed and attractive guest houses, as well as all the new buildings, at the Universities newly constructed, and, of course, also the new automobile plants, fertilizer, steel, and other plants all these enter the national income at their current costs and regardless of whether they will ultimately add to the national output, as the fertilizer and steel plants my, or be a perpetual drain, as the automobile plants are and will continue to be.

For the purpose of judging progress, the increase in consumption is much more meaningful than the increase in total output, both because its measurement is less ambiguous and because the aim of development is, after all, to raise the consumption level of the populace. Even the official figures show that per capita consumption has risen at the rate of only one per cent per year.

Some growth in total output but at a disappointingly slow rate and with a widening, rather than a narrowing of the distribution of income: that is the conclusion suggested by all the evidence. I met no Indian economist who did not agree with this general verdict.

Just how disappointing the rate of growth is can be judged by measuring it against a standard that is repeatedly set forth. Time and again one will hear as an article of faith in India that the economic and political pressure for development is so urgent that India must develop at a faster rate than Western countries did. A standard cliché is that India must compress into decades what took other countries centuries. There is, of course, much merit to this position. The scope for improvement is tremendous, the desirability of improvement is unquestioned; and it should be easier and faster to imitate than to initiate. But the actually achieved rate of 4 growth to date is lower than was achieved in Britain, the United States, and the developing countries during their early stages of development. It is lower than the current rate of growth in Japan, Greece, Israel, Formosa or in Italy, France, and Germany, Even at the officially estimated 1 1/2 per cent per year growth in per capita output, it would take over a century of steady growth at that rate for India to reach the current level of per capita income in Japan, and well over three centuries to reach the current level of per capita in the U.S. The current danger is that India will stretch into centuries what took other countries decades.

And all this under circumstances that have most been very favorable for economic growth. he achievement of independence from Britain raised many real problems, particularly as a result of partition, the relocation of populations, and the bloodshed between Hindus and Moslems. But it also created real opportunities. For decades, the enthusiasm and energy of a sizable fraction of the ablest people of India had been devoted to the independence struggle. They had themselves been engaged in activities that were not merely neutral but actively hostile to economic development and they had persuaded a large of fraction their countrymen to do likewise. Independence released these energies and made them available to promote economic progress. Independence also fostered a weakening of rigid social and economic arrangements, increased flexibility in institutions, greater mobility of people, and in general an environment more suited than before to change. Finally, the years after independence saw a great inflow of resources form abroad. External assistance during the decade spanning the first two five-years plans averaged about 1 ½ per cent of national income, which means that it provided something like a fifth of net investment; and external assistance was disproportionately concentrated in the second five-year plan period, when it amounted to about 2 ½ per cent of national income or to over a fourth of net investment. One that score alone, growth should have accelerated during the second five-year plan rather than apparently slowing down a bit.

What is the reason for the disappointingly slow rate of growth? One frequently heard explanation is that it reflects the social institutions of Indians, the nature of the Indian people, the climatic conditions in which they live. Religions taboos, the caste system, a fatalistic philosophy are said to imprison the society in a strait jacket of custom and tradition. The people are said to be un-enterprising and slothful. The hot and humid climate of much of the land saps energy.

These factors may have some relevance in explaining the present low level of income in India, but I believe they have almost none in explaining the low rate of growth. Certainly the visitor to India is forcibly struck by the enormous waste of resources, in terms of his own system of values, produced by the holiness of the cow, to take the most obvious example of the economic effect of religious belief. India has one of the highest if not the highest of cows per person in the world, yet the water buffalo is the primary source of milk, and of course beef is almost unavailable as food. Cows wander freely in the streets of major cities, most of them scrawny, poorly cared for, and of little or no economic value. Yet they invariably have the right of way and, poorly as they are fed, doubtless absorb a very large aggregate amount of foodstuffs that could be made available for human consumption. The rigid assignment of tasks to specific castes often means that two or three people are required to do a job that one person, willing to turn his hand to everything, could perform.

Similarly, human qualities are certainly important. A dramatic illustration from India is the differential experience of two groups of refugees from Pakistan after partition: the Punjabis and the Bengalis. The Punjabis have doubled the average agricultural yield in the area in which they resettled, and have besides been among the most enterprising, active, and dynamic business groups in India. The Bengalis have had great difficulties in resettling, many of them are still in government resettlement camps some 15 years after partition, and they have been a drain on the country rather than a source of growth.

But none of this explains a lack of growth. Insofar as the religious and social customs make for inefficient use of resources, they will keep the Indian level of output lower that otherwise put they need not prevent it from rising at a rapid rate along that lower path. One the contrary, a change in religious and social attitudes, such as is unquestionably occurring, provides an additional reason to expect growth. There need not be a complete reversal of attitudes. A 5 to 10 per cent per year increase in total output would be a very satisfactory record need. To contribute to this, there is required only a small and gradual substitution of attitudes more favourable to the effective use of resources.

The same thing is true about human qualities. It is not necessary that every individual be an enterprising, risk-taking economic man. The history of every nation that has experienced economic growth shows that it is a tiny percentage of the community that sets the pace, undertakes the path-breaking ventures, coordinates the economic activity of the host of others. Most people everywhere are simply hewers of wood and drawers of water. But their hewing of wood and drawing of water is made far more productive by the activities of the minority of industrial and commercial innovators and the much larger but still tiny minority of imitators.

And there is no doubt that India has an adequate supply of potential entrepreneurs, both innovators and imitators. Indians who migrated to Africa to South East Asia have in country after country formed a major part of the entrepreneurial class, have seen the dynamic element initiating and promoting economic progress. It is hard to believe that those who left India are radically different from those who stayed at home. The clearest evidence that they are not is currently provided by the dramatic growth of small-scale industry in the Punjab. The most encouraging experience during my stay in India was a visit I made to Ludhiana, a medium sized town in the Punjab which is fast becoming a major centre for the production of machine tools, bicycles, sewing machines, and similar Items, and which has long been a major centre for the production of knitted goods. Here was the Industrial Revolution at its inception – I repeatedly felt that I was seeing in true life the descriptions of Manchester and Birmingham the end of the 18the century that I had read in economic histories. There are thousands of small and medium size workshops, with extraordinarily detailed specialization of function. Here was a three man shop where saddles for bicycles were being assembled from parts which in turn were made by other small enterprises. But here also was bicycle factory employing hundreds which purchased many of its parts from the smaller firms, and the output of which had been growing at the rate of 50% a year. One of the owners of the factory who showed me around was particularly proud of the part he and his associates had played in helping their employees to establish independent firms. Here was a small open cubby-hole on the main street in which with the aid of a few tools, a thirty-ton press was being constructed, but here also a firm on a substantial scale making many machine tools, mostly with tools that it has in turn made itself. There is no shortage of enterprise, or drive, or technical skill in Ludhiana. There is rather a self-confident, strident, raw capitalism bursting at the seams.

One reason why Westerners so often feel that enterprise and entrepreneurial capacity is lacking in India is because they look at India with expectations derived from the advanced countries of the West. They think in terms of the large, modern corporation, of General Motors, General Electric, and other industrial giants. But it was not firms like this that produced the Industrial revolution; they are, if anything, its end products. The hope for India lies not in the exceptional Tatas or similar giants, but precisely in the hole-in-the wall firm, in the small and medium size enterprises, in Ludhiana not Jamshedpur; in the millions of small entrepreneurs who line the streets of every city with their sometimes miniscule shops and workshops. If the tendencies so evident in Ludhiana could be given full rein, and not hampered and hindered in every direction by governmental interference and control, India could achieve a rate of growth that would exceed today’s fondest hopes.

As this final remark suggests, the correct explanation for India’s slow growth is in my view not to be found in its religious or social attitudes, or in the quality of its people, but rather in the economic policy that India has adopted; most especially in the extensive use of detailed physical controls by government.

“Planning” dose not by itself have any very specific content. It can refer to a wide range of arrangements: to a largely laissez-faire society, in which individuals plan the use of their own resources and government’s role is limited to preserving law and order, enforcing private contracts, and constructing public works; to the recent French policy of mixing exhortation, prediction, and cooperative guesstimating; to centralized control by a totalitarian government of the details of economic activity. Along still different dimension, Mark Spade(Nigel Balchin), in his wonderful book on How to Run a Bassoon Factory and Business for Pleasure defined the deference between a planned and an unplanned business in a way that often seems letter-perfect for India. “In an unplanned business”, he writes, “things just happen, i.e. they crop up. Life is full of unforeseen happenings and circumstances over which you have no control. On the other hand: In a planned business things still happen and crop up and so on, but you know exactly what would have been the state of affairs if they hadn’t”.

In India, planning has come to have a very specific meaning, one that is patterned largely on the Russian model. It has meant a sequence of five-year plans, each attempting to specify the allocation of investment expenditures and productive capacity to different lines of activity, with great emphasis being placed on the expansion of the so-called “heavy” or “basic” industries. A Planning Commission in New Delhi is charged with drawing up the plans and supervising their implementation. There is some decentralization to the separate states but the general idea is centralized governmental control of the allocation of physical resources.

Whether because of the adoption of the Russian model of economic planning or for other reasons; Russia and India have one feature in common that strongly impresses the casual visitor. In both, if I may pervert a phrase made famous by our present Ambassador to India, there is a striking contrast between public affluence and private squalor. In both countries, whenever one sees a magnificent structure, newly built or well maintained, the odds are heavy that it is governmental. If some activity is luxuriously financed and well provided for, the odds are that is governmentally sponsored. The city in India which showed the most striking improvement since my earlier visit was New Delhi, with impressive new governmental buildings, residence and luxury hotels. I should add that although the public affluence is not notably different in the two countries, the private squalor is much worse in India than in Russia.

Though Indian economic planning is cut to the Russian pattern, it operates in a different economic and political structure. Agricultural land is almost entirely privately owned and operated; so are most trading and industrial enterprises. However, the government does own and operate many important industrial undertakings in a wide variety of fields-from railroads and air transport to steel mills, coal mines, fertilizer factories, machine tool plants, and retail establishments; Parliament has explicitly adopted “the socialist pattern of society” as the objective of economic and social policy; a long list of industries have been explicitly reserved to the “public sector” for future development, and the successive plans have allocated to public sector investment a wholly disproportionate part of total investment – in the third five-year plan, 60 percent although the public sector accounts at present for not much more that a tenth of total income generated. In addition, the government exercises important controls over the private sector: no substantial enterprise can be established without an “industrial” license from the government, existing firms must get government allocations of foreign exchange and also of domestic products in the public sector; and so on in endless variety.

The difference between India and Russia in political structure is at the moment even sharper that in economic structure. The British left parliamentary democracy and respect for civil rights as a very real heritage to India. Though I very much fear that this heritage is being undermined and weakened, as of the moment it is still very strong indeed. There is tolerance of wide range of opinion, free discussion, open opposition by organized political parties, and judicial protection of individual civil rights-except for recent emergency actions under the Defence of India Act.

The kind of centralized economic planning India has adopted can enable a strong authoritarian government to extract a high fraction of the aggregate output the people for governmental purposes – Russia is a prime current example and China, though we know much less about her, may be another; Egypt under the Pharaohs is a more ancient example. This is one way, and I believe almost the only way, in which such a system can foster economic growth-if the resources extracted are indeed used for productive capital investment rather than for arms or governments. But this advantage- if advantage it be – of centralized economic planning, India is not able to obtain precisely because of the difference between its economic and political structure and those of Russia or China.

For the rest, centralized economic planning is adverse to economic development. First, and most basic, it is an inefficient way to use the knowledge available to the community as a whole. That knowledge is scattered among millions of individuals each of whom has some special information about local resources and capacities, about the particular competence of particular people, characteristics of his local market, and so on in endless variety. The reason the free market can be so efficient an organizing device is because it enables this scattered information to be effectively coordinated and each individual to contribute his mite. Centralized economic planning substitutes the knowledge and information available at the centre for this scattered knowledge. The people at the centre may individually be exceedingly intelligent and informed much more so than the average participant in the economic process. Yet even so their combined knowledge is meagre compared to that of the millions of people whose activities they are seeking to control and coordinate. It is the height of arrogance – or perhaps more realistically, of ignorance – for central planners to suppose otherwise.

In the second place, growth is process of change; it requires flexibility, adaptability, and the willingness to experiment; above all, is a process of trial and error that requires an effective system for ruthlessly weeding out the errors and for generously backing the successful experiments. But centralized economic planning tends to be cumbersome and rigid. So-called plans are laid out long in advance and it is exceedingly difficult to modify them as circumstances change. Inevitable and necessary bureaucratic procedures mean that the right hand does not know what the left hand is doing, that a long process of files going up the channels of communication and then coming back down is involved in adjusting to changing circumstances. Above all, the unwillingness to admit error, and the political costs of doing so, mean that the unsuccessful experiments are rarely weeded out; unless they are failures of the most extreme kind, they will be subsidized, protected, supported, and labelled successes.

India’s publicly operated steel plants provide a current example. These were built for India by foreign countries; one by the British, one by the West Germans, and one by the Russians. All are apparently technologically efficient and modern mills. They are repeatedly cited as great achievements of Indian economic planning. Yet, on probing, it will be admitted that their costs are much higher than those of the private steel firms, despite the much older and less modern facilities possessed by the latter. Part of the explanation is apparently the extension to their administration of the Civil Service administrative system developed for very different purposes. A senior civil servant, who has had no experience in steel whatsoever and has perhaps only a few more years to retirement, is posted to be in charge of a steel plant, and many of his subordinates will be similarly recruited. Whatever the explanation, the inefficiency can continue because the firms are propped up by restrictions on the import of steel and by domestic prices that may be too low to restrict the amount demanded to the amount available and yet are high enough to give the private firms very satisfactory profits indeed.

A third major defect of centralized economic planning is the strong tendency for planners to go in for prestige projects- to leave monuments to their activity, perhaps in the form of flashy international airlines, perhaps of highly mechanized factories when more labour -intensive techniques would be better suited to the country’s needs, perhaps of luxury hotels like the Ashoka, or perhaps of major dams when a large number of small scale tube wells might be far better.

These defects of central planning impressed me greatly when I was in India eight years ago. But despite them, I was then inclined to guarded optimism. In summarizing my conclusions at that time for the International Cooperation Administration (predecessor of AID), on whose behalf I had been in India, I wrote; “The basic fact about Indian economic development is that there has begun a breaking down of traditional attitudes and social arrangements that promises to release great reserves of private energy and initiative. India is on the move. The underlying forces making for change are so powerful that I think India can stand much unwise-economic policy………………………..”

“Looking forward, I am optimistic about the chances for growth, not because of the projected five-year plan but despite it. The ambitious plans for government investment and projects, if carried through, will I am persuaded involve waste of capital resources; impressive public plants are a sort of twentieth century Taj Mahal. But India can stand this waste provided it does not lead either to open inflation or to an extensive and deadening network of direct controls designed to suppress inflation”.

Unfortunately – and this is the major reason for my present pessimism- the second of these provisos has been contradicted. Price rises in India during the second five-year plan period have produced an extensive and deadening network of direct controls, particularly in connection with foreign exchange and foreign trade. These controls have not yet stifled completely the momentum for growth, but they have distorted it greatly, have made for enormous waste of resources, and are a major factor undermining political freedom and democracy.

The Achilles heel of the Indian Economy at the moment is the artificial and unrealistic exchange rate. The official exchange rate is the same today as it was in 1995. In the interim, prices within India have risen some 30 to 40 per cent; whereas prices in the US, UK, and Germany have risen far less, at most by 10 per cent. If the rupee was worth 21 cents in 1955, it clearly is not worth 21 cents today. And even in 195, India was experiencing difficulty in balancing its payments. It was even then engaged in extensive foreign exchange control, import restrictions, and export subsidies.

The attempt to maintain an over-valued rupee has had far reaching effects —- as similar attempts have had in every other country that has tried to maintain an overvalued currency. The rise in internal prices without a change in the official price of foreign currency has made foreign goods seem cheap relative to domestic goods and so has encouraged attempts to increase imports; it has also made domestic goods seem expensive to foreign purchasers and has discouraged exports. As a result, India’s recorded exports have risen much less than world trade a whole, while the demand for imports has steadily expanded.

The pressure on the balance of payments has been officially met in three ways: first, by using up large foreign exchange reserves; second, by getting additional assistance and loans from abroad; third, by extending direct controls over imports and subsidizing export. There has been a fourth unofficial way, namely, black market transactions in exchange and the smuggling of goods. Though no records exist on this fourth way, there is little doubt that it has expanded greatly as it increasingly renders official statistics unreliable as measures of India’s foreign trade transactions. For example, though the number of tourists entering India in recent years has been growing, the amount recorded in official statistics as spent by tourists has been declining.

Exchange control has not in fact been able to stimulate exports. They have stagnated or fallen. It has operated almost entirely by preventing individuals form importing as much as they would like at the controlled exchange rate. In doing so, it has done immense harm to the Indian economic and political structure. There is no satisfactory criterion available to the planning authorities to determine what items and how much of each should be permitted to be imported. There is much talk of restricting “unessential” imports and permitting only “essential” ones. But this is just talk unless there is some way of determining what is and what is not essential. In the absence of a market test, there is in fact no satisfactory way to do so. When a family must reduce its expenditures, it does not cut out whole categories of goods; it cuts its expenditures a little here and a little there, balancing the loss from spending a rupee less on toothpaste with that from spending a rupee less on toothpaste with that from spending a rupee less on moves and so on in infinite variety. The same principle applies in restricting imports to the amount that can be purchased with the foreign exchange available. But how can planners at the counter have the necessary information about each of the tens of thousands of items imported?

How can they know how much a little cut here will reduce exports of a hundred other items? How costly it will be to provide domestic substitutes, directly or indirectly? How much the consumers of the ultimate products would be willing to sacrifice in other directions for a little more of a particular import item?

The fact is that the planners cannot possibly know what they would have to know to ration exchange intelligently. Instead, they resort to the blunt axe of cutting out whole categories of imports; to the dead hand of the past, in allocating a certain percentage of imports in some base years; and to submission to influence, political and economic, which is brought to bear on them. And they have no alternative, since there is no sensible way they can do what they set out to do.

Automobiles provide a striking example of the economic waste produced by this policy. In the name of restricting “luxuries” to “save foreign exchange”, the importation of automobiles from abroad is in effect prohibited, whether these are second hand or new. But at the same time, new automobiles, copies of foreign makes, are being produced at very high cost in small runs under extremely uneconomic conditions at three (?) different plants in India. These are available by one channel or another for the luxury” consumption it is said to be desirable to suppress. Many of their components are imported, and many of those made in India use indirectly imported materials. The result is that not only is the total cost of the amount of motor transportation actually produced multiplied manifold, but even the foreign exchange cost is probably larger.

The results are most striking in the market for second hand cars. A car that I sold before I left the US for $22 (a) 1950 Buick) was being quoted in Bombay when I was there at 7,500 o 10,000 rupees or $1,500 to $2,000 at the official exchange rate and over $1,000 at the free market rate. Clearly, the sensible rate and cheap way for India to get automobile transportation is to import second-hand cars and trucks from abroad. Aside from the direct saving through getting the cars cheap, this would have great indirect advantage in promoting technical literacy, using the abundant manpower resources of India, and conserving capital. But India in effect says, “We are too stingy to buy second-hand motor vehicles, we must buy new ones.”!

Some very crude estimates I have made suggest that the extra amount India is currently spending annually to acquire motor vehicle transportation is of the order of one-tenth of annual US aid. This fraction of our aid is simply being thrown away to support conspicuous production.

What is true of automobiles is true in industry after industry India has become a protected economy in which items are produced at a multiple of the costs at which they could be obtained from abroad. and at the same time, foreign exchange is wasted in purchasing goods abroad for which it would be more economical to use domestic substitutes (like the domestic repair and maintenance of second-hand automobiles which would be a substitute for the import of materials for the production of new ones.)

Needless to say, in spite of the proliferation and extension of direct exchange controls, it has not been possible in fact to maintain the artificial exchange rate. Aside from black market transactions, the various explicit promotion schemes and restrictions on imports have the effect of making the actual exchange rate different from the official one. For example, a manufacturer of sewing machine heads who was exporting some told me that he sold he same head for 132 rupees in India, and for 7 pounds sterling abroad. This works out to an exchange rate of 19 rupees to the pound sterling compared with the official rate of 13 ½ rupees. Other rates that I calculated in the same way varied from 15 to 26 rupees to the pound. If similar comparisons of internal and external price were made for import items, the range would be even wider. Through the adoption of expedient after expedient in attempting to shore up an artificial rate of exchange, the planners have in fact created a multiple exchange rate system that not one of them would be willing to defend as rational if he examined the whole structure explicitly.

Though the controls in the field of foreign exchange are the most widespread and destructive at the moment, their adverse effect is reinforced by a whole series of other domestic controls. For example, steel is rational to users, who spend much time and energy is reshuffling allocations and distributing the steel more rationally. Some of the entrepreneurs at Ludhiana estimated that an eighth to a quarter of their working time was being spent on either getting allocations or finding ways to acquire the materials they needed by more devious channels.

Aside from the economic harm they do, the controls are doing enormous harm to the political fabric of Indian society. Corruption and petty bribery are of course universal, and not only in underdeveloped societies. But they have been reaching new heights in India. On my earlier visit to India, I heard almost nothing about explicit corruption in the higher ranks of the civil service, though much about political influence. On this visit, there was widespread talk on all sides, and in the press, about bribery of government officials, the securing of favors by contributions to political parties and so on and on, with even the naming of names, in private conversation, of very highly placed persons directly involved. A standard jest heard over and over was that while the U.S. might be an “affluent society”, India was an “influence society”. A major reason for the corruption is that the techniques of economic planning employed in India have put relatively minor civil economic value. An import licence, carrying with it price, can often be sold at once for double or triple its nominal value. Much the same is true of a permit to acquire steel at the controlled price. Industrial licence, access to credit on specially favourable terms, or to other special programmes designed to “promote” development in one direction or another, and so on, add further to the stimulus to corruption provided in all countries by large scale governmental expenditures, with the opportunities they offer for juicy contracts. C. Rajagopalachari, the first Indian Governor-General after Independence and currently the octogenarian leader of the opposition Swatantra (Freedom) party, has labelled the existing system a license-and-permit raj, and people of every political persuasion admit the aptness of the label. The westerner who has formed his opinion of India solely from what he has read about it is likely to have the impression that a strong central government is at times ruthlessly and always forcefully shaping private conduct to further what it regards as the public interest. In fact, it would be no less accurate to describe the situation as one in which powerful private groups are able, through political and financial influence, to use governmental policy as an instrument to further their own interests.

Corruption undermines the political heritage directly by destroying the moral and the efficiency of the civil service, and by undermining respect for law on the part of the public at large. But the factors that give rise to it operate in more subtle fashions as well. The newspapers, for example, are subject to newsprint rationing; moreover, they are for the most part owned by persons who also have large interests in industrial concerns heavily dependent on government for licenses, permits, and orders. It clearly is the better part of valour for them to mute their criticism of the government in power, and certainly this reader of the papers had the impression that they did so, avoiding any general criticism, and restricting criticism to specific points. For example, as a result of the Chinese episode, a not-negligible fraction of the intellectuals I met, even those strongly in favour of the general economic policies for the government, have become disenchanted with Nehru and believe that he should be replaced. Yet I read not a single editorial or column in any major English-language newspaper voicing such a view. Published statements to this effect were either in explicitly party organs or in small -circulation personal journals. I head of one journalist who had been discharged from a leading newspaper because of anti-Nehru comments in his articles. Three persons who circulated a public letter after the Chinese invasion urging that Nehru be replaced were held in jail for some months without ever being brought to trial and then re-released. While I heard different stories about the extent to which this event had even been reported in the press, apparently none of the newspapers conducted a vigorous editorial campaign about the incident. The major protects were by private committees and through public meeting. As a final item, a leading businessman who was a strong backer of the Swatantra party cited as a sign of his courage and independence that he had given as much money to Swatantra as to Nehru’s Congress party !

Though these trends are important and may ultimately be decisive, let me repeat that, as of the present, India is, on any absolute scale, a remarkably free country with a high respect for civil and political right. That is why there is still so much hope and why it is so important to recognize and alter the policies that are threatening its internal freedom.

On one level, there is ground for optimism about India. I am myself still persuaded, as I was in 1955, that India lacks none of the basic requisites for economic growth expect a proper economic policy. I believe that drastic but technically feasible changes in economic policy-the substitution of a freely floating exchange rate for the present fixed rate and elimination of the exchange controls, import restrictions, and export subsidies designed to prop up the present rate; and a similar policy of substituting the free market for direct controls in the domestic economic scene could release an enormous reservoir of energy and drive and produce a dramatic accelerate of economic growth in India comparable to that which occurred in Japan after the Meiji restoration.

On another level, however, I am exceedingly pessimistic. The intellectual climate of opinion about economic policy is almost wholly adverse to any changes in the direction that seems to me required. There is a deadening uniformity of opinion in India, particularly among economists, about issues of economic policy. In talks to and with students and teachers of economics at a number of universities, Personal of the planning commission, economists in the civil service, financial journalists, and business men, I encountered again and again the same stereotyped responses expressed often in precisely the same words. It was as if they were repeating a catechism, learned by rote, and believed in as a matter of faith. And this was equally so when the responses were patently contradicted by empirical evidence as when they were supported by the evidence or at least not contradicted.

There is only one prominent professional economist, Professor B.R. Shenoy of Gujarat University, who is openly and publicly and at all effectively opposed to present policies and in favour of greater reliance on a free market. He is a remarkable and courageous man. In 1955, when the second five-year plan was in preparation, the government appointed an advisory committee of 21 professional economists to criticize the draft framework that had been prepared by Prof. Mahalanobis. The committee submitted two reports. One, signed by 20 economists, was largely a restatement of the draft framework and contained hardly any critical comments, though doubtless many of the signers had strong individual reservations on specific points. The other was a minority report by Prof. Shenoy, which criticized the fundamental structure of the proposed plan, and pointed out in detail where difficulties would arise and what their character would be. If one reads Shenoy’s report now, it sounds like a retrospective description of what happened rather than a forecast. But needless to say, tough most economists display a deep respect for Shenoy’s courage and personal qualities; he remains a prophet without honour in his own country.

There are a few younger and less well known economists who deviate from the dominate opinion, and there are many who share the main tenets of the dominant view yet differ on particular elements – for example, on the desirability of maintaining the present exchange rate. There are more numerous persons in the business world, particularly some connected with the Swatantra party, who recognize the defects of detailed centralized planning, and the virtues of a greater reliance on the market. But even among business men, most grumble about details but accept the views of the professional economists as necessarily right in the main. I shall not soon forget the tongue lashing I received from a prominent and highly successful manufacturer when I made remarks into which he correctly read implicit criticism of India’s current economic policies. Of course, many of the currently most successful businessmen have a great stake in the existing system. The virtue of a free market is that it is profit and loss system. If it were permitted to operate, it would quickly and ruthlessly weed out many who are currently protected by the ubiquitous controls. In India as in the United States, existing private entrepreneurs are in practice among the most effective enemies of free enterprise.

It will, I fear, take a major political or economic crisis to produce a substantial change in the course on which India is no set in economic policy, and I am not at all optimistic that such a crisis if it occurs will produce a shift toward greater freedom rather than toward greater authoritarianism.

Publication of this essay here made possible by Centre for Civil Society(CCS). The Editors would like to thank CCS for their kind permission.