8 Laws That Must Be Axed Right Now

Archaic, unnecessary and absurd laws riddle our statute books. They must go.

When the Modi government tabled two bills in Parliament within four months of each other, repealing many outdated and redundant laws, it appeared to be living up to Modi’s promise during the 2014 election campaign that his government would repeal 100 laws in 100 days. Between them, the two Repealing and Amending Bills (tabled in August and December 2014) are set to repeal 124 Acts, a fact the government has been tom-tomming. According to reports, in March, the cabinet green-flagged a bill to repeal 758 appropriation Acts.

Hold the standing ovation a bit, though.

Only four of the Acts taken up the Repealing and Amending Bills are principal (or the main) Acts.

The rest—all 120 of them—are amendment Acts, that is, Acts which amended provisions of principal Acts and having done so, have served their purpose. Some amendment Acts have been passed as late as 2013.

As for the appropriation Acts, they anyway have a short life. They authorize expenditure for one financial year, sometimes less, and cease to be relevant after that.

Meanwhile, Acts dating back to the 1830s are still around (see box “Making No Sense”).

Culling out outdated and redundant laws and junking them, is a periodic exercise that Indian governments have taken up. It’s called scavenging but, as the box “Junking Exercises” shows, this was a regular exercise between 1950 and 1964, but then ran out of steam. Unless laws come with a sunset clause built into them, they continue to exist and could either become a source of harassment and misuse by authorities or provide convenient loopholes to escape more stringent laws that came later.

Many committees and commissions have identified outdated laws that need to be axed without spending too much time on them. These include various Law Commissions, the LARGE (Legal Adjustments and Reforms for Globalizing the Economy) Project, helmed by economist Bibek Debroy (who is a member of Swarajya’s Editorial Advisory Board) in the early 1990s and the Commission on Review of Administrative Laws (the P.C. Jain Commission) in the late 1990s. The latest Twentieth Law Commission has submitted four interim reports on the subject to the present government. There has also been a civil society initiative, The 100 Laws Project, in which three organisations—Centre for Civil Society, National Institute of Public Policy and Finance and Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy—collaborated (This author has been involved in this exercise). All of them have suggested the repeal of a large number of laws. The Jain Commission alone listed 1,300 central laws that needed to be axed.

Little has changed on the ground, though. The Twentieth Law Commission has noted that 253 laws that earlier the Law Commission reports had suggested repealing continue to exist. Though all the committees and commissions recommended repealing the principal Acts, governments have largely focussed on amendment Acts. In 2001, the Atal Behari Vajpayee government repealed a staggering 300-odd laws. Over 90 per cent of them were amendment Acts.

What explains this preference for amendment Acts? Well, they—and appropriation Acts—are low-hanging fruits which do not require the government to apply its mind about the likely effects of their repeal. This is a lazy approach, which even the current government seems to have happily adopted.

The 100 Laws Project, which identified 100 laws ripe for repeal out of all the laws earlier commissions had considered, found that there were no legal issues arising from the repeal of most of these. In some cases, reference to the Act had to be removed from other Acts; in some other cases, pending litigation could be affected but this matter could be taken care of by enacting a saving clause.

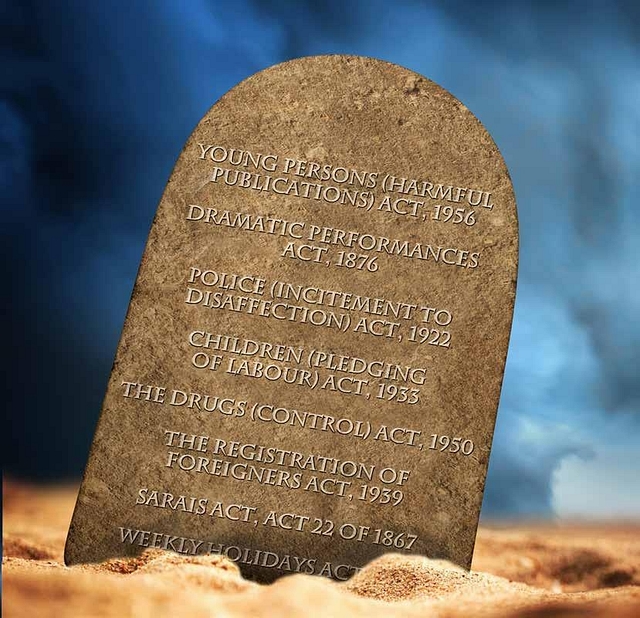

Here are eight laws that could have been safely taken up for repeal, but were not.

Sarais Act, Act 22 of 1867

Communications Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad loved to tell this tale when he was Law Minister and piloted the first Repealing and Amending Bill in August. A five-star hotel in Mumbai, he said, had cases filed against it to allow anyone and everyone to use its toilets since, technically, it was a sarai. The Act defines a sarai as any building used for the shelter and accommodation of travellers. Sarais have to be registered and the magistrate can refuse to register the keeper of a sarai if the person does not produce “a certificate of character”.

The Law Commission’s first interim report notes that the Act is redundant because hotels are registered under state-level legislations. These are anyway matters in the State List of the Constitution and there is no logic for the continuance of a central law on the subject. But the Act remains in place and local authorities across the country insist on hotels, lodges, guest houses and resorts registering themselves under the Act. Prasad may have quoted the story about the Mumbai hotel to underline the absurdity of the Act, but he himself failed to put it in the list of Acts that the repealing Bill he piloted mentions.

Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act, 1956

You may be a non-smoker or even a non-inhaler, you may even be an extremely strait-laced person, who just happens to love reggae legend Bob Marley. But if you are in Kerala, just don’t wear a Bob Marley T-shirt or carry any Marley memorabilia. You could get booked under Section 3(1) of the Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act, 1956.

The Act bars the sale of “harmful publications” described as “any book, magazine, pamphlet, leaflet, newspaper or other like publication” which depicts commission of offences, acts of violence or cruelty and incidents of a repulsive or horrible nature in a way that will corrupt young persons. It is a cognizable offence, involving six months jail or fine or both. The Act also allows the police to seize and confiscate the offending publication.

How liberal the interpretation of publication is becomes evident from what happened across Kerala in March 2014.

The police decided that Marley—who warbled about smoking “de ganja until the very end”—was the inspiration behind Kerala youth turning to drugs. Shops and stalls stocking Marley T-shirts and other stuff were raided and booked under the Act. One store in Kochi was even asked to change its name—Ganja.

Is this just a simple case of over-enthusiastic and ham-handed police action? Should there be no regulation at all on the kind of content that publications put out? There can be a larger debate on censorship, but the fact is that there are enough laws to deal with the issue of objectionable content. The 100 Laws Project report points out that various sections of the Indian Penal Code, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Act, 1989, Protection of Human Rights Act, 1976, Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012, deal with the issue of offensive, communal, secessionist, racist, casteist and indecent speech as well as pornography. In addition, there are regulations relating to content in print, electronic and online media.

Dramatic Performances Act, 1876

In 1953, two plays got caught up in court battles. In Kerala, Ningalenne Communistakki (You Made Me A Communist), got banned under the Dramatic Performances Act for propagating subversive ideas and encouraging people to rebel against the government. In Lucknow, the local branch of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) was taken to court for staging a play based on a Munshi Premchand story, Idgah. Apart from being charged with not obtaining a licence to stage the play, disobeying prohibitory orders (about the play) and not submitting a copy of the play prior to the performance, IPTA was also accused of having “distorted the script of the story to suit their political ideology”.

The Dramatic Performances Act was passed by the British to check plays with a hidden message of independence being staged. Long, long after the British left, the Act continues to empower state governments under state-specific Acts to prohibit the staging of plays that they deem scandalous or defamatory in nature, likely to excite feelings of disaffection towards the government and to “deprave and corrupt” the audience. The text of the play has to be submitted to the authorities three days before the performance.

The fact that the Idgah performance was sought to be banned because an additional magistrate felt that the play distorted the original story, shows how arbitrary and capricious the enforcement of the Act can be. Can a bureaucrat sit in judgement over the interpretation of a literary work?

There have been many cases of the Act being used to ban performances and courts have said that the provisions of the Act are against Article 19 of the Constitution guaranteeing a fundamental right to freedom of expression. The Kerala High Court lifted the ban against Ningalenne Communistakki, two months after it was imposed. The case against Idgah was dismissed by the Allahabad High Court, again invoking Article 19. In 2013, the Chennai High Court held that certain sections of the Tamil Nadu Dramatic Performance Act violate Articles 14 (right to equality) and 19 of the Constitution.

Making No Sense

Why are close to 300 British era laws, some enacted even before the 1857 Mutiny, still in force? Most of these were a response to specific situations. Here’s a sample from a list of 20 which The 100 Laws Project compiled:

– The Bangalore Marriages Validating Act, 1934, enacted to validate marriages conducted by one Walter James McDonald Redwood who believed he was authorised to do so. It’s doubtful if even those whom Mr Redwood got married are still alive.

– Forfeited Deposits Act, 1850, which dealt with an issue relating to forfeiture of deposits as a result of a British regulation of 1819.

– The Sheriff’s Fees Act, 1852, detailed the remuneration of sheriffs in the former Presidencies of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay. The British themselves repealed all but one provisions of the Act by an amending order in 1937.

– Fort William Act, 1881, which allowed the British Chief of Army to make rules within Fort William in Calcutta on certain listed subjects.

– The Reformatory Schools Act, 1897, which sent first-time juvenile offenders to reformatory schools. The Act got overridden by the Juvenile Justice Act, 1986, which itself got repealed by the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000. But the 1897 Act has not been formally repealed.

There is no princely state of Oudh any more, and yet at least five laws relating to it remain in the statute books.

– The Oudh Sub-Settlement Act, 1867, legalised rules that the Chief Commissioner of Oudh had issued for people who had subordinate rights of property in the formerly princely state.

– The Oudh Estates Act, 1869, defined the rights of taluqdars and other landholders in certain estates of Oudh. Like Oudh, taluqdars too do not exist any more.

– The Oudh Taluqdars Relief Act, 1870, allowed taluqdars to settle their debts with their mortgaged immovable property.

– The Oudh Laws Act, 1876, declared and amended the laws to be administered in Oudh.

– The Oudh Wasikas Act, 1886, related to certain allowances and pensions paid to the royal family and its heirs.

If British era laws continue, can one dare hope for the repeal of laws enacted to deal with post-Partition issues? Here are three of them:

– Trading with the Enemy (Continuance of Emergency Powers) Act, 1947, was meant to appropriate the property of Pakistani nationals. The Enemy Property Act, 1968, does the same thing.

– Exchange of Prisoners Act, 1948, facilitated the exchange of persons committed to custody on or before 1 August 1948. The Consular Access Agreement signed in 2008 now governs exchange of prisoners.

– Indian Independence Pakistan Courts (Pending Proceedings) Act, 1952, nullifies orders and decrees passed by former British courts which, post-Partition, fell in Pakistan.

Police (Incitement to Disaffection) Act, 1922

In September 2013, the Andhra Pradesh police filed a case against the Hyderabad resident editor of The Hindu. The newspaper had carried a report about the director-general of police visiting a local religious figure. The headline said “DGP visiting Old City godman raises eyebrows”, and the report carried a picture of the DGP sitting with folded hands before the religious figure and also said that he had carried some files with him.

The resident editor was booked under Section 3 of the Police (Incitement to Disaffection) Act. The section prescribes six months jail and a fine of Rs 200 or both to anyone intentionally causing “disaffection towards the government…among members of a police force” or induces any member of a police force to withhold his services or indulge in indiscipline. Disaffection is not defined and can be interpreted in any way someone planning to invoke the Act wants to, as is evident from the Hyderabad case. How the article could spread disaffection among the police force or encourage policemen to resort to indiscipline is befuddling.

The law was enacted by the British, perhaps to quell rebellion within the police forces and was first invoked against Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak. Does it have a place in independent India?

It is not just the loose wording of the Act that is problematic, the Act is out of sync with the Code of Conduct for the Police in India issued in July 1985. The Code, the report says, requires members of the police force to maintain high standards of discipline, perform duties in accordance with the law, obey lawful directions, maintain calm in the face of danger, scorn or ridicule, and practise self-restraint. In any case, the first interim report on obsolete laws by the Twentieth Law Commission says the law infringes Article 19 of the Constitution.

The 100 Laws report says the repeal of this Act would not create any legal issues, except that reference to it would have to be removed from five other Acts.

Children (Pledging of Labour) Act, 1933

Just about six months after anti-child labour activist Kailash Satyarthi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, it is probably politically incorrect to say that a law on this subject should be scrapped. But when a law could prove counter-productive, then it is probably best to red flag it.

The Children (Pledging of Labour) Act, like all laws on child labour, is well-meaning in its intent. It seeks to check the element of voluntarism in child labour by prohibiting parents from giving children up for work through an agreement. But the enactment of the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, which sets out where and how children could or could not work renders this 1933 law obsolete.

However, since it still continues in the statute books, there is a potential problem. Like all stringent laws, the 1933 Act has a loophole. Section 3, which expressly disallows such agreements, makes an exception in the case of agreements which were made without detriment to the child, where reasonable wages were paid or where the services of the child can be terminated in a week. However, it is silent on what is detrimental and what a reasonable wage is. The National Commission of Labour recommended the repeal of this Act in 2002 as it felt this vague wording could provide an escape hatch. It also found the Act inconsistent with the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Drugs (Control) Act, 1950

This law was sought to be repealed in 2006 and a repeal Bill tabled in the Lok Sabha. The Bill lapsed when the Lok Sabha was dissolved three years later; it was not even referred to the standing committee.

The Act was enacted in 1950, when belief in market forces to check prices was low and there was a general feeling that pricing of drugs should not be left entirely to the market. It set maximum prices of certain essential drugs that were brought under the Act and maximum quantities that could be bought, sold or stocked. The penalty for violating the law was stiff—three years jail or fine or both.

Later, drugs were brought under the Essential Commodities Act, 1955 and orders issued under Section 3 of this Act monitored the pricing of essential drugs. Drug (Prices Control) Orders have been issued periodically from 1970 onwards and right now the 2013 Order is in force. There’s also a National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority in place to look into the issue of pricing. It makes no sense, therefore, for the 1950 Act to remain.

The Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939

India is not exactly known to be a friendly place for foreign tourists. But it is equally—if not more—difficult for foreigners staying on for long periods, either for work or to study. Much of their problems arise from the Registration of Foreigners Act, which requires foreigners who stay in India beyond three months to register themselves with the Foreigners Regional Registration Office and report their entry, movement and departure to the authorities.

There are enough stories in the public domain about foreigners being put through harrowing times because of this and how this Act is proving to be a major source of corruption and extortion. Enforcement is also weak, with the government having no way of checking if foreigners staying on beyond three months are, in fact, registering themselves or providing information about their movements.

The fact that the law was passed during the Second World War is proof that it was meant to serve a specific wartime purpose and its continuance 75 years later is baffling. As the 100 Laws report points out, there are other laws—the Foreigners Act, 1946, and the Passport Act, 1967, which provide the means to track the entry and movement of foreigners. The Passport Act provides reasonable opportunity to an aggrieved person to seek redress and provides protection at the time of arrest. The 1939 Act does not.

Weekly Holidays Act, 1942

If it is not bad enough that the State needs to dictate that offices and commercial establishments should be given a day off, there is actually a central legislation on the subject, which falls squarely within the State List. The Weekly Holidays Act insists on employees of shops and commercial establishments being given a day off every week.

In any case, every state has its own Shops and Establishments Act which also mandates shops and commercial establishments to be closed one day in a week and employees to be given a weekly off. What’s more, this Act applies only to areas notified by state governments. Strangely, Karnataka has its own Shops and Establishments Act enacted in 1961 which applies to 29 sub-divisions, but the Weekly Holidays Act applies to six areas in Kudagu district and one in Raichur. In the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Act applies only to the Port Blair municipal areas.

The Twentieth Law Commission in its fourth interim report has recommended the repeal of this law, provided that every state has its own Shops and Establishments Act. But the fact that the Act currently applies only to specific areas in two states shows that either all states already have a Shops and Establishments Act or the enforcement of this Act is not at all effective since states are getting away by not implementing it or enacting a Shops and Establishments Act.

But then, the pointlessness of this particular law is hardly an exception to the rule, as far as statute books go.