CSR Is Good Business Sense

The basic philosophy of Corporate Social Responsibility for an organization has to be “enlightened self-interest”.

In an age of rapid and pervasive globalization, modern organizations are struggling hard to survive and grow in a rapidly changing business scenario fraught with uncertainty, recession and turbulence. When the profit motive appears to be the dominant drive in business leaders operating in an aggressively competitive environment, the question arises: Where is the scope for directing our efforts to discharge our Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)?

The government of India has made it mandatory for companies to invest 2 percent of their net profits in specifically identified and scheduled CSR activities. But hardly a few companies are even aware of what CSR is, in essence, and how to go about delivering the initiatives around CSR. This is a big challenge.

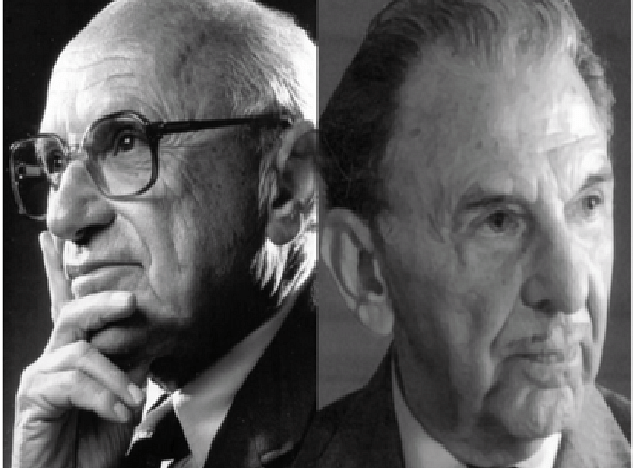

Let us go back to 1970. On September 13, 1970, The New York Times published an article by Milton Friedman where he wrote: “The only social responsibility of business is to make profits.” The very same year, J.R.D. Tata instructed all the Tata group companies to include a clause on Stakeholder Management in their Articles of Association.

The Tata Group, with its century-old culture and cherished values, always remained a glowing example of an authentic synthesis of business interests and social concerns. However, it was only during the last decade of the last century that growing interest in CSR among the business community worldwide became discernible. Questions were raised on the ultimate goal of business activity and the nature of relationship between the business organization and the social context in which it is embedded. Are there things in business life more important than merely chasing numbers and targets? All significant changes in history begin with asking some deep and even disturbing questions. CSR was no exception.

What were the factors that were responsible for this development of interest in undertaking CSR initiatives? With the wildfire spread of globalization, business leaders began to realize that we live in an interconnected world where interdependence forms the basis of our existence and progress. For the survival and sustained growth of business itself, apart from anything else, it is not sufficient to limit our thoughts and concerns within the boundary of the organization. Thus the spectrum of initiatives around CSR is an ever-expanding one that may start from the employees and shareholders but includes the customers, the suppliers, the social milieu, the government, the natural environment and even the competitor. There has been a shift from preoccupation with interests of shareholders to engagement with and concern for multiple stakeholders from diverse constituencies. At a micro level, with the championing of transparency as a value that demands availability and smooth flow of information, companies can no longer afford to manipulate customers and arm-twist vendors. At a macro level, corporate leaders are compelled to consider the impact of their business decisions on the community and the environment at large—the distant others.

Further, with increasing dependence on the stockmarket for financing, there is also the growing need to attract and fulfill the expectations of investors who value the goodwill of companies that invest in CSR initiatives. CSR today is not just a part-time philanthropic activity but a strategic imperative directly linked to business results for long-term sustainability of organizations.

It must also be mentioned that the scope of CSR is no longer limited to monetary donations for a social cause. Companies need to reconsider their new roles as partners and facilitators in development and participate in capacity-building programmes for the disadvantaged sections of the society. This will raise the standard of living, increase the purchasing power of people and thereby expand the markets for selling their own products and services.

Also, such initiatives by any company also boost the morale of the employees by instilling in them a sense of pride and ownership. This has a direct and positive impact on their level of motivation and enhances productivity. Engagement with CSR makes good business sense.

Conversely, companies in which employee satisfaction level is low are likely to be the least effective in CSR initiatives. It is not possible to generate goodwill in the external environment without taking good care of the needs and aspirations of the staff. Charity begins at home.

As to the “drivers” of CSR, they could be both external and internal. Public policy guidelines, environmental regulations, labour laws and the like constitute the external drivers. Among the internal drivers, the most important is the commitment of top management to CSR. If the leadership has real positive intent and passionate involvement, it can creatively expand the nature and scope of CSR interventions.

Sometimes it becomes necessary to partner with NGOs, and social organizations to address those needs of the community that do not come within the core competence of the organization. Business schools, transnational NGOs and multilateral organizations have also come forward by designing courses and training programmes to improve the quality, impact and evaluation of CSR efforts.

It may now be worthwhile to revisit the Indian concept of seva, loosely translated as “service”. In our present understanding of service, the provider of the service emerges as the benefactor and the receiver the prime beneficiary. The true spirit of seva implies just the reverse. Here the service provider is the prime beneficiary because the receivers have given him an opportunity to serve.

Swami Vivekananda founded the first Indian transnational organization way back in 1898. He created the Ramakrishna Mission to spread the message of his spiritual master Sri Ramakrishna worldwide, to be “atmanomokshartham jagathitaya cha”—“for the salvation of the self and the welfare of the world”. Vivekananda had a truly global vision while organically rooted in Indian culture and ethos. This extraordinarily dynamic monk was the first and probably the most powerful spiritual ambassador of India who spread the profound messages of this blessed land and attracted people from the West to join his mission. During his voyage to America, his fellow traveller was another inspiring leader, J.N. Tata, the father of Indian industrialization. For days they discussed the future for India. Wasn’t this a divine coincidence?

Another signal contribution from India is the concept and model of Trusteeship as propounded by Mahatma Gandhi. He was deeply inspired by the thoughts of the eminent 19th century British literary figure John Ruskin who held responsible the dominant self-interest-based economics for bringing “schism into the Policy of Angels and the Economy of Heaven”, and also Tolstoy, who exhorted humanity with his message “The Kingdom of God is within you”. Moreover, the concepts of aparigraha (non-possession) and samabhavana (equality or oneness with all) of the Bhagavad Gita had a strong influence on Gandhi’s formulation of Trusteeship. The Gita is the crystallized wisdom of the Upanishads. No wonder the Ishopanishad says: “Tena tyaktena bhunjitha (Enjoy by renunciation).”

Central to the concept of Trusteeship are Gandhi’s views of “property” and “entitlements”. Trusteeship is a means of transforming the capitalist order of society into an egalitarian one. It is based on the faith that human nature is never beyond redemption and the owners can be reformed. It does not recognize any right to private property beyond what may be permitted by society for its own welfare. The charter of production will be determined by social necessity and not by personal whim or greed. The owner will manage the property for the service of society as a trustee and he will be entitled to a statutory commission that cannot be exorbitant. It may be worthwhile to recall Gandhi’s famous remark: “The world has enough for everyone’s need but not enough for everyone’s greed.”

The concept of Trusteeship may sound strange to the proponents of individualism and free enterprise, but the caution of Martin Luther King may be worth a while to ponder over—that if we ignore Gandhi it is at our own risk!

The basic philosophy of CSR for an organization has to be “enlightened self-interest”. A visionary leader has the ability to expand the notion of the “self” of the organization beyond its premises to include all stakeholders and even the absent others. If that notion is limited, we end up calculating our narrow self-interest, and fail to see the deep linkages with others. But an enlightened leader with an ever-expanding view of the organizational “self” can naturally see the connectedness with others. He is inspired by his conviction and not bogged down with calculations.

For truly enlightened leadership, it is necessary first to light the fire in one’s heart and ignite the mind. Keeping CSR as a top priority among the agenda items in one’s diary helps to retain focus in the midst of the frenetic chase after the bottom line. Perhaps the best time to refocus and to take stock of the day’s activity is before dropping off to sleep. That is when one can attempt to contact the innermost self and warm oneself by the light within. The results will come. A different day will dawn, fashioned by such a person.