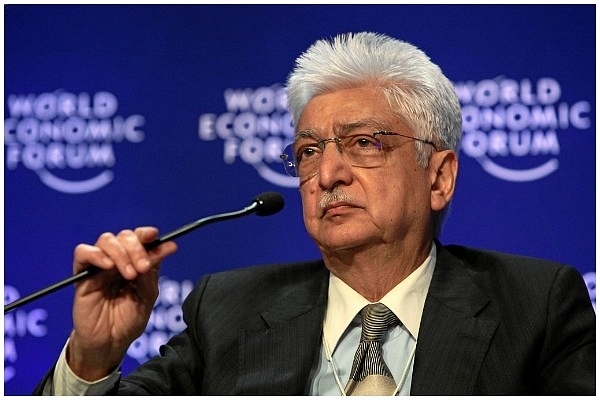

Differentiated Voting Lessons From Azim Premji

Indian entrepreneurs need to remain in charge of the companies they created from scratch even while raising capital and diluting their stakes.

Is a middleground possible?

There is little doubt, given the growing hunger for capital, both to revive growth and to finance innovation, that we need to create two categories of shares – one with more voting rights and the other with higher economic rights. The former enables more entrepreneurship and risk-taking, the latter helps bring in capital. While technology-based start-ups will benefit by giving their promoters higher voting rights in the companies they create, the same will also help government navigate a tough political climate where resistance to privatisation is high, but demand for capital cannot endlessly be met by passing the hat around to the hapless taxpayer.

Whether it is public sector banks or Air India or Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (BSNL), as long as they remain in the public sector, they will need equity to stay afloat. Air India has been a bottomless pit for capital for the last decade or so. BSNL and its puny sister MTNL have been losing money hand-over-fist for years now, thanks to the intense competition in the telecom industry, especially after the entry of Reliance Jio with low data tariffs in September 2016. Between 2016-17 and 2018-19, BSNL is estimated to have lost nearly Rs 20,000 crore (About MTNL, the less said the better). Neither company has the surpluses needed to get rid of excess staff, or pay for the spectrum needed to launch full-scale 4G services, leave alone the 5G challenge that looms later this year. While the public sector telcos do own large tracts of land that can be sold to raise capital, government has been particularly unsuccessful in raising money from land sales due to the complexities involved. VSNL’s excess land is still to be monetised, even though the company was privatised 17 years ago and sold to the Tatas.

As for banks, given the overload of bad loans, they are forever in need of capital. The simple and straightforward way to do this is privatisation, but there is no political consensus for it; in the meantime, the best compromise is to create shares with differential voting rights, with government holding the controlling interest and private shareholders the economic stakes with entitlements to dividends and bonuses.

In the private sector, differentiated voting rights will enable entrepreneurs to retain control of their companies for longer periods even when they are forced to raise huge amounts of capital to grow their businesses. Without such special voting rights, the Bansals will always have to sell out to the Walmarts, and sooner than later, the Paytms and Olas will be foreign-owned in a situation where domestic capital is expensive but foreign capital is cheap and bountiful.

But even as we wait for legislation to allow two types of shareholding power, an interesting via media seems to be emerging from an unexpected area: private philanthropy. In March, billionaire Azim Premji handed over economic ownership of 67 per cent of his shareholdings in infotech major Wipro to two charitable trusts, the Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives Private Limited, and Azim Premji Trust, leaving only the balance seven per cent-and-odd remaining shares with his family. But here’s the interesting bit. While the trusts will get dividends and bonus shares, the voting power on these shares will be exercised only by Premji. Put another way, Premji has effectively created shares with differential voting powers, with the 67 per cent that is gifted away always voting with his formally held seven per cent stake.

It is not clear how exactly this happy situation has been legally arrived at, but it is possible to conceive of ways to do so even with the Flipkarts of the world. What it would need is to allow foreigners (or domestic investors) to buy your shares, but with a clear legally-binding undertaking that these shares will vote with specified promoters for a specified period, and subject to certain performance metrics being achieved by the latter. This will effectively ensure that promoters with higher voting rights focus on entrepreneurship and performance, while the economic owners benefit from the rising valuations of a well-run company. At some future date, when the company is profitable, they can also expect dividends and other economic benefits from this ownership. They can also buy back voting rights when they want the old promoters to leave.

The benefit of such an arrangement is that it gives both sides an incentive to keep its half of the bargain: from the effective owners of capital, a promise of non-interference in management and corporate strategy, subject only to board oversight and direction; and from the promoters a promise of performance. Since such agreements can be limited by time and performance metrics, both sides have reason to cooperate and work together. Also, in some cases, this may be better than legally enforceable dual voting rights. If an entrepreneur underperforms, his voting rights cannot automatically be curtailed by those with lower voting rights, except with very high majorities. But with legally binding contracts, this may be easier to do.

The Premji method of separating voting from economic rights is even more valuable for India’s growing band of billionaires and millionaires, who are wealthy on paper, but hesitate to give their shares to charity because of fear of loss of control over their companies. It is easy to claim that Mukesh Ambani’s wealth is a humongous $55 billion, but if most of it is tied to his control of Reliance Industries, which surely needs his entrepreneurship in the foreseeable future, he can hardly just gift it away. Even assuming that he wants to keep economic ownership of a quarter of that, which will be good enough to keep his family and descendants in comfort for generations to come, he will not do so if gifting the balance 75 per cent means potential takeover threats. The only way around this is the Premji formula, whatever that is, of separating economic ownership from voting power.

Of course, there are limits to such duality. When economic shareholding is totally divorced from voting power, the incentive to perform grows weaker over time, especially when voting power shifts from the original promoter to his family or successors, who may not have the same passion, skills or drive to keep creating value. So, differentiated voting power is not necessarily an unmixed blessing. At some point, voting power and economic ownership need to converge to align incentives. But right now, at the juncture where cheap foreign capital finds it easy to edge out domestic promoters, the pendulum has swung away from entrepreneurship towards conglomerate power.

A related development that will help the process is separation of ownership from management – a process that happened naturally in the West when the need for capital automatically forced owners to dilute their stakes. Over generations, the heirs of the original promoters merely became significant shareholders who did not run the company. American inheritance taxes also helped create this separation, but in India, crony capitalism and the lack of an inheritance tax (or estate duties) have together conspired to let owners remain owners for too long, often without any commensurate performance. Today, the insolvency and bankruptcy code (IBC) is breaking the back of crony capital, where poorly performing managements are being divested of ownership – albeit slowly.

Inter-generational equity demands that India should legislate inheritance taxes and differential share voting powers to encourage two important ingredients of growth: high quality entrepreneurship that does not lose control too soon, and high-quality managerial resources that remain committed to all shareholders and not just promoters who may have earned their voting powers from inheritance, not performance.

This separation of voting power from economic ownership, and management from promoter interests, is useful to encourage philanthropy and performance.