18 Months In, Here’s How GST Has Fared On The Ground

GST has brought in some gains; these could have been more but for the hasty launch that has resulted in implementation problems still being fixed.

It is indeed a tragedy for India that one of its most transformational tax reform exercises has been subjected to political squabbling of a very juvenile kind. “Gabbar Singh Tax”, says Congress president Rahul Gandhi. “Grand Stupid Thought”, counters Prime Minister Narendra Modi, referring to the Congress demand for a single rate.

Goods and services tax (GST) deserves better, much better — even though a rushed-through launch has resulted in less than perfect implementation, resulting in piecemeal fixes being done through the first 18 months.

The revenue collections have been below expectations, crossing the Rs 1 lakh crore mark only twice since July 2017 (see Table 1). “These are not happy numbers,” says Kavita Rao, professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy. One reason is the series of rate reductions that have happened; the other is that compliance levels by taxpayers continue to be low, as replies to questions in Parliament show. The percentage of taxpayers who did not file returns rose from 14 per cent in July 2017 to 28 per cent in November 2018 (See Table 2). Cases of evasion detected have also increased — the number of cases detected between March and December 2018 is 52 per cent of the total number of cases detected in 2016-17 and 2017-18 combined; the value of such evasion is 87 per cent of the combined value of the previous two fiscals (See Table 3). There are reports about ghost companies registering for GST, raising fake invoices, taking advantage of various input tax credits and then disappearing.

So, was GST a bad idea?

No. GST, undoubtedly, is a superior tax. It ushers in a more efficient indirect tax structure, reduces costs for businesses and final price for consumers and brings in more revenues for the government. The initial teething troubles, a spike in inflation and a dip in economic growth are worth the larger gains for the economy.

Does India’s GST measure up? M Govinda Rao, former member of the Fourteenth Finance Commission, nails the issue succinctly: “GST is a good reform. It has worked to the extent it can, given the structure and the technology platform.”

To what extent has it worked, exactly?

In simplifying the tax system, to a limited extent. There is no denying that GST has hugely reduced the phenomenon of tax-on-tax that marked the earlier value-added tax (VAT) regime. Some cascading continues because petroleum and electricity — two major contributors to cascading — are not included in GST. But this is as good as it gets for now, until states agree to bring these under the GST ambit.

GST is also the reason India is coming closer to the semblance of a common market — rates for a particular good or service are common across states. Earlier each state had a different rate. To that limited extent, it can claim to be one nation one tax (though the term actually refers to a single rate GST across goods and services). Anil Bharadwaj, secretary of the Federation of Indian Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (FISME), cites this as a major positive.

Notwithstanding the periodic rate reductions (on 400 groups of goods and 96 groups of services, till date), GST has resulted in some stability and predictability in tax rates. “The rate is no longer a cause of business disruption,” says Sunil Sinha, principal economist, India Ratings.

Large companies with multi-state operations have been able to prune their distribution costs. Anita Rastogi, partner, indirect tax and GST at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) points out that a number of companies have reworked their warehouses which had been set up to deal with central sales tax. A PwC paper, ‘365 Days of GST: A Historic Journey’, notes that “consolidation of storage points and a reduction in the number of inefficient nodes in supply chains” has seen companies reduce their distribution costs by 8 per cent to 12 per cent. This also has a positive impact on inventory management and working capital.

Yet, these positives cannot hide the fact that the GST, which came into effect on 1 July 2017, is not the good and simple tax that the government claimed it was. This is the structure problem that Govinda Rao is referring to.

There are actually six slabs — 0-2(for bullion)-5-12-18-28 - plus a cess. Adding to the complexity, many commodities and services attract different rates depending on (a) price — footwear, clothing, cinema tickets below a certain price are taxed lower than those above the threshold; (b) feature — biscuits and breakfast cereals, for example, are taxed differently depending on whether they are chocolate coated or not; (c) status of the buyer — one example that the PwC paper cites is construction work contract services being taxed differently when supplied to the railways and the metro.

This is not about not taxing milk and Mercedes — two entirely different categories — at the same rate (the standard government riposte to demands for a simpler structure); it is about differentiating within categories. This just opens up avenues for evasion by tax payers as well as harassment by the tax bureaucracy.

Several industries are faced with an inverted tax structure — the tax they pay on inputs is more than the tax levied on their product. “This erodes their competitiveness at a time they are already finding it difficult to compete with cheap Chinese imports,” points out Bharadwaj. This also results in accumulation of the input tax credit (ITC) due to them, something that puts a strain on smaller businesses.

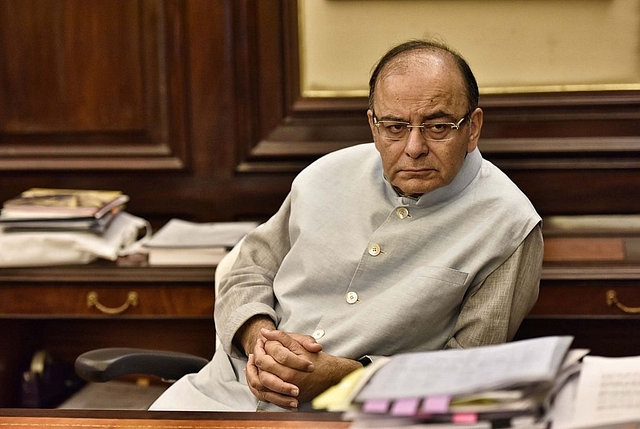

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley is now talking about a much simpler structure of zero, 5 per cent and a standard rate of between 12 per cent and 18 per cent. He, however, has hinted at retaining the 28 per cent rate on luxury and sin goods, which many find pointless. “The 28 per cent category doesn’t make sense. Bringing it down to 18 per cent will not lead to huge revenue loss and it will simplify matters for input tax credit,” says Govinda Rao.

Has GST worked for businesses?

Again, to some extent, in terms of stability and predictability in tax rates, a uniform rate for a particular good or service across the country, and a reduction in logistics and distribution costs.

However, the pain has been more than the gain for smaller businesses. Sure, things are much better than the harrowing early days, which saw the GST Network (GSTN) frequently acting up. The GST Council has also been more than proactive in easing the compliance burden for them, the latest move being to increase the threshold for registering for GST from Rs 20 lakh to Rs 40 lakh (though states fearing revenue loss have been given the option of retaining the lower threshold). A number of small businessmen this writer spoke to admitted there has been a vast improvement. Ganesh Gupta, president of the Federation of Indian Export Organisations, also acknowledges that a number of problems exporters were facing have been resolved.

And yet, several pain points remain, and some steps to ease the compliance burden have led to other problems.

Early into GST implementation, the reverse charge mechanism (where a large supplier registered with GST would pay the tax on behalf of the small, unregistered supplier and claim ITC) was put on hold until September 2019. As a result, says Haseeb Drabu, former finance minister of Jammu and Kashmir, small businesses have lost their supply network, with large businesses preferring to buy from other large, registered businesses, who would pay their own GST.

When the GSTN repeatedly crashed in the initial days, the burden on the system was reduced by allowing small businesses to file quarterly returns (now annually, after the January 10 GST Council meeting). However, large businesses continued to file monthly returns. As a result, Drabu points out, matching these becomes a problem. Similarly, two of the three returns that were mandated initially were suspended, again because the system could not cope. In their place, a summary return has to be filed, but, Rastogi notes, there is no software for matching taxes paid and set-offs against them.

Companies were then asked to file an annual return, with self-audit by a chartered accountant. The return was initially to be filed by 31 December, but the very lengthy and complicated format was notified only in September. The filing date has now been extended to 31 March.

And though, on paper, all processes are online, the tax bureaucracy has found ways to bring back onerous paperwork, as the exporter community is finding. According to FIEO, the refund process for ITC is not under electronic data interchange (EDI), unlike the refunds on integrated goods and service tax (IGST, which is levied on inter-state transactions). While exporters file the application electronically on the GSTN, the application has to be printed out and submitted to the relevant jurisdictional tax authority.

These authorities hesitate to accept the application, perhaps because 90 per cent of the amount has to be released within seven days on a provisional basis. That is why there is often a discrepancy between the refund figures cited by exporters (based on applications filed) and by the government (based on applications accepted and pending). Figures cited in Parliament show disposal rates of refund applications of 95 per cent by the Centre and 83 per cent by the states. Several state-level tax authorities, Gupta says, ask for documents that are not specified under the relevant rules. And because part of the process is manual, there is no system-driven monitoring to ensure that exporters get the provisional refund speedily.

In addition, while ITC refunds for exporters from the central goods and services tax (CGST) is fairly prompt, states tend to drag their feet on refund of the state goods and service tax (SGST) component. “Dealing with two authorities increases our problems,” says Gupta, pointing out that delay in a Rs 5 lakh refund could cripple operations of small exporters.

Could all this be a case of the empire striking back? Drabu believes it is. GST, with its self-assessment model, has meant loss of clout for the tax babus, whose revenge was to introduce complicated paperwork, he says. Businessmen having to deal with them in the states admit that speed money has to be coughed up — up to 2 per cent of the refund amount. “There are many stakeholders affected by the structure and design of GST — only the tax department’s point of view is being heard,” rues Kavita Rao.

The e-way bill is becoming another nuisance point. Amid the initial euphoria about falling logistics costs for businesses and faster movement of trucks, a few states complained that revenue from IGST was not commensurate with the increased movement of goods. They were sure companies were evading GST. Hence, e-way bills were introduced for inter-state movement of goods worth more than Rs 50,000. The bill has to have details of invoice, truck number, kilometres to be covered, duration of journey (the norms fix certain time periods and, in case of any delay, breakdown or accident, the invoice has to be re-issued). The entire process is online and, to be fair, barring the server crashing on the first two days when it was started initially in February 2018, it has functioned smoothly since it was resumed in May. Checking is only random, in case of any suspicion.

“Conceptually, this is a recipe for disaster; it is like handing a stick to the tax administration and asking them to stand on the road,” says Kavita Rao. And despite e-way bill defenders insisting it does not involve inspectors checking every truck, her worst fears appear to be coming true. Most states have set up mobile squads to conduct surprise checks and this has bestowed opportunities for harassment and corruption, since the penalty includes an upfront fine as well as confiscation of goods. A truck that has reached its destination and is parked on the road because the warehouse has closed for the day and there is no place to park it until the next morning, could invite penalties; trucks transporting personal goods face harassment in some states. According to Rastogi, multiple cases regarding e-way bills have been filed in high courts.

Is the e-way bill system worth the effort? Right now, Rastogi points out, the e-way bill portal and the GSTR-1 (the return form which summarises all sales) are not linked; once that is done, she is sure evasion will become much more difficult.

There’s another spectre hovering over businesses — the National Anti-Profiteering Authority (NAA) and state-level screening committees. The genesis of this also harks back to the innate suspicion about the private sector on the part of politicians and bureaucrats; they were sure companies would not pass on the benefit of rate cuts to consumers unless a big stick was wielded.

When the NAA came into existence, the then revenue secretary Hasmukh Adhia pooh-poohed concerns about the likely return of inspector raj, assuring the nation that it would not initiate suo motu investigation but only act on complaints, which would then be subjected to thorough investigation. Assurances were also given that small businesses and retailers would not be affected; it was only supposed to keep large businesses in check.

However, the document setting out the procedure and methodology on the NAA website states quite clearly that it can look into any failure to pass on rate cuts on its own as well as in response to a complaint. In the 10 months since its first order in April 2018, the NAA has passed 30 orders; of these, only nine have been negative, with those getting rapped on the knuckles ranging from large companies like Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) to local grocery shops. Defenders of the anti-profiteering mechanism can point to just nine adverse orders to argue that it is not something to be feared. On the other hand, this also indicates that the problem of rate cuts not being passed on is not as huge as it was being made out to be and 21 companies or retailers have been subject to unnecessary investigation.

As in the case of e-way bills, legal challenges have started. In November 2018, realty firm Pyramid Infratech got a stay on a NAA order issued in September. HUL is also mulling legal options to challenge the adverse order passed against it, according to media reports.

Regardless of the anti-profiteering mechanism, have consumers benefited from GST? The government claims they have because the prices of many commonly consumed commodities have come down. Rastogi says prices of many FMCG (fast moving consumer goods) have reduced. However, whether that has sustained is difficult to determine, despite the elaborate anti-profiteering mechanism. And traders may be making quite a few quick bucks by levying GST on the maximum retail price (MRP) which actually includes the tax; many consumers don’t know this. But certainly, inflation has not been the devil it was expected to be — it has been moderate, at worst.

The various state-level Appellate Authority for Advance Rulings (AAARs) were bringing in their own set of problems. They often give conflicting orders, as has happened in the case of solar power projects when the Karnataka and Maharashtra AARs gave different orders. “There are 280 advance rulings and a majority of them don’t make sense,” says Rastogi. Fortunately, the GST Council, in December, suggested the setting up of a Centralised Appellate Authority for Advance Rulings. When that comes into effect, its ruling will be binding in case of any conflict between the orders of two or more state AARs.

So, has GST worked for government revenues?

Not as much as it was expected to. The pinch will be felt more by the Centre; direct tax revenues have posted robust growth this year, but it is not clear if this will help plug the shortfall in revenues from GST. State revenues are protected until 2022. States are assured a 14 per cent annual growth over their pre-GST revenues in 2015-16 for five years from the launch of GST. Any shortfall between this projected and actual revenue growth would be met from a compensation fund that is financed by a cess on the items in the 28 per cent GST bracket.

States have not been doing too badly. Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Telangana have logged revenue surpluses (growth above 14 per cent in 2018-19, which means they don’t need to be compensated), while some are just short of the 14 per cent growth (see box: compensation to states). Some are not showing any improvement in reducing the shortfall because their revenues from pre-GST levies that have now got subsumed in GST were very high; a group of ministers, assisted by NIPFP, is going to look into this more closely.

Many economists are uncomfortable with the compensation formula. They see it as a fallout of the rush to launch GST — it was this assurance that helped overcome the last vestiges of resistance among states. “State revenues have been growing at 10-11 per cent a year; what was the logic behind 14 per cent assured revenue growth?” asks Pinaki Chakraborty, professor at NIPFP and economic adviser to the Fourteenth Finance Commission.

Drabu feels this gives states a blanket insurance against inefficiency. “There is no incentive to collect revenue,” he says, pointing out that the apprehension that producer states will lose and consumer states will benefit proved misplaced. Maharashtra, a manufacturing state, did not lose because it started getting revenues from services (which only the central government used to tax earlier) while Jammu and Kashmir, a consumer state, lost out because of bad implementation, he says.

It is because of this revenue shortfall that states are not willing to let petroleum products (which account for between 35 per cent and 40 per cent of states own tax revenue) be brought within the GST ambit. “The only way to bring these in is to substantially increase buoyancy of revenue, so that states don’t feel they are losing out,” says Govinda Rao.

That, he says, requires big reforms, the top ones being solving the technology problems and rationalising rates. Both will improve compliance, pushing up revenues in the process.

It is a pity that many of the operational problems occurred because of the GSTN portal. “The vision on technology is super,” says Rastogi. Many countries, she points out, do not have such a tech-driven tax administration, with each and every transaction being mapped on the portal. “But GSTN was launched without enough time for testing,” she rues.

Indeed, one reason for higher evasion rates in the post-GST scenario is improved detection, enabled by technology. Rastogi points out that the phenomenon of fake invoices was detected through big data analytics by the GSTN. And this can only improve as the technology is fine-tuned and more points of matching with different GST returns income tax returns are enabled.

Increasing the threshold for registration under GST is going to be a huge leg up in this respect because it will reduce the burden on the GSTN. Govinda Rao points out that businesses with turnover between Rs 20 lakh and Rs 50 lakh accounted for 70 per cent of assesses while contributing only 4 per cent to revenues. The higher registration threshold will free up a lot of resources to focus more sharply on detecting and checkmating evasion.

Despite the various problems, no one is writing off GST. Govinda Rao calls it a work in progress. “There will be many iterations before we stabilise,” says NIPFP’s Kavita Rao. The rate reductions and easing of compliance burdens that have happened until now have all been driven by politics rather than a genuine need for a good and simple tax. But there’s no need to carp about the motivation if it takes GST to the point of stabilisation sooner rather than later.