India And The Dark Side Of Tech Platforms

At a time of conflict between the incumbents and emerging platforms, here are six questions that the Indian state, economy, and society must answer.

Veles in Macedonia isn’t a place that is in the consciousness of most people in Europe, let alone Americans and Indians. Yet, Veles was the centre of massive fake news factories that are said to have played an important role in the 2016 US elections. Technology platforms were used to organise large numbers of anonymous people, post fake news that algorithms sliced-diced and disseminated to target groups, and to make and receive payments.

You can also read this article in Hindi- भारत और तकनीकि मंचों का अहितकारी पक्ष

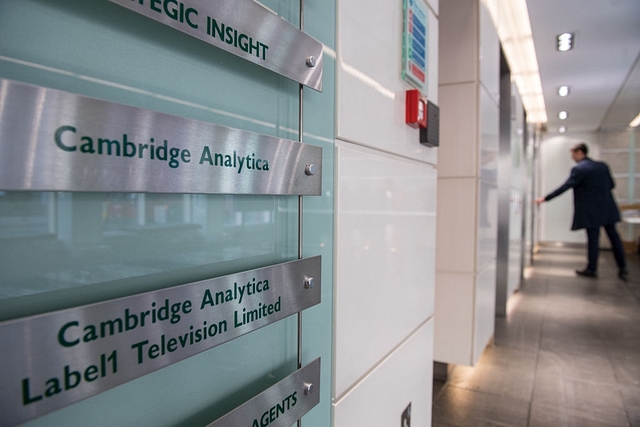

What is clear, and more so after the Cambridge Analytica scandal, is that technology platforms like Facebook can and will be used to anonymously and (adversely) influence people, policy and elections through means that are, at best, manipulative and at worst, illegal.

Unsurprisingly, this has grabbed the imagination of the world given the role played by global technology platforms like Facebook, Amazon, Alibaba, Netflix, Google, Microsoft, Apple (FAANGMA) and others to lives and livelihoods around the world.

The European Union (EU) has acted fast by enacting the General Data Protection Rules, acknowledging the key role played by technology for individuals and societies alike. Denmark has appointed the world’s first tech ambassador as part of its Foreign Ministry, based in Silicon Valley with a global mandate that spans Copenhagen, Beijing and Silicon Valley.

Technology platforms — based on big data, algorithms, cloud and mobile phones — are very disruptive creations. Unlike mere products, platforms are ‘products’ that allow the creation and orchestration of an ecosystem of players — suppliers, vendors, consumers, brokers, payers — that is, in effect, co-opted to serve the needs of the platform while serving their own interests. This creation and orchestration is fuelled by large sums of capital, and happens very rapidly and at scale with profitable outcomes — at least initially — for the participants.

The platforms themselves soon become ‘too big to fail’ with the big becoming bigger, using capital and leading-edge technology to drive behaviours of players, guiding product offerings, pricing, deliveries and even customer choice and, over time, dramatically disrupting industries and the people who make a living from these industries.

There are many kinds of technology platforms ranging from the global positioning system (GPS) to Android to operating systems to the likes of the better known FAANGMA.

In a largely uneducated but surprisingly well-connected society like India, the impact and consequences of undesirable outcomes via technology platforms can be severely detrimental. Unfriendly overseas powers, powerful lobbies and special interests could adversely impact and even alter the India polity itself.

We have seen how WhatsApp forwards were used to disseminate fake news and motivated stories that incited dangerous and violent behaviours. So much so that in July of this year, the government had to direct WhatsApp to take urgent steps to prevent the spread of irresponsible and explosive messages amid cases of lynching.

The recent fracas involving the Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Associations of India (FHRAI) and OYO Hotels, MakeMyTrip and Goibibo (the latter two are a merged entity) is a case in point. The FHRAI has accused the companies of breach of contract, hosting illegal and unlicensed accommodations and predatory pricing.

What is clear is that five-year-old OYO Hotels’ technology platform has dramatically changed India’s hotel industry: relating to the pricing, availability of large and growing room inventory, efficient discovery of this inventory, the processes that govern relationships between existing players, the promise of a consistent branded experience and enhanced revenues to inventory owners of more than 50 per cent within a month of joining the OYO network.

The power has shifted to OYO from the agents and hotel owners. Backed by over $1.5 billion in venture capital, OYO is valued at over $5 billion (more than two times India Hotels, which owns Taj group of hotels) and growing at over 100 per cent per annum. It has over 270,000 rooms in its inventory (without owning a single one), employs over 700 software engineers out of 8,500 employees. Technology drives decision-making giving OYO unmatched speed, predictability and reliability.

Or, take the case of eight-year-old Ola. It has over 1 million vehicles operating across its network of 169 cities including a recent foray into Australia. None of these vehicles is owned by Ola. With over 6,000 employees, Ola is backed by over $3 billion in venture capital funding and valued at well over $4 billion. Ola has added food delivery to its transportation business that includes cabs, autos, e-vehicles and bicycles. Ola is the market leader in India for providing transportation on demand.

Not surprisingly, those adversely impacted by the rise of Ola and by its practices have taken to protests, court cases and to the media. These include taxi drivers, industry operators and some in the civil society.

Private banks like ICICI, HDFC, Citi, Standard Chartered and others have very recently come together to prevent financial technology (fintech) companies from accessing consumer data for credit scoring and for providing incentives. Fintech companies are technology platforms that are unregulated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) — unlike the banks — and have no assets, and don’t come under RBI norms.

Concerns about data security and privacy are raised by the incumbents, who are clearly affected by the rise of fintech companies. Paytm and PhonePe are fintech platform companies that are impacting the payments industries.

Naukri is a technology platform that affects recruiters, job-seekers and human resource departments. Swiggy and Zomato are reorganising the restaurant industry — restaurant discovery and selection, food choices, consumer types, pricing and deliveries. Similarly, there are many other emerging technology platforms in India that are built on top of other platforms like Android, Google and AWS.

Are the fears of the industry incumbents unfounded? Any industry disruption that upsets the incumbent architecture of the industry and its players is bound to result in a backlash. But to be fair to the incumbents, it is important to ask the following questions, especially in India, where the socio-economic conditions are far removed from those in the developed world, institutional oversight is lax, regulatory frameworks are evolving, awareness amongst citizens is low and the enforcement machinery is poor:

1. Are platforms subject to the same rules and laws as the incumbent players? Incumbents have to conform to rules that protect consumers, workers, communities and markets. Why not technology platforms? What is the liability of a technology platform in cases of a breach of data or misuse of services or inaccurate presentation of information that is provided by a third party?

2. The nature of tech platforms is such that the big get bigger. Marginal costs are close to zero. And very soon, thanks to capital and technology, monopolies, duopolies or oligopolies emerge. Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Google and Microsoft are global examples. How then does one ensure that this power isn’t misused?

For example, the high incentives, commissions and discounts paid to participants (including consumers) to lure them into the network can easily be raised to predatory levels over time once the ‘monopolist’ position is established. How should this be dealt with?

3. The large amounts of capital and sophisticated technology can be used to squeeze out competition through appropriate economic incentives and terms of engagement with existing participants. How do regulators ensure there’s transparency and fairness? The famous case of the mid-1990s where Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer in its Windows operating system to kill the popular Netscape browser, comes to mind. Or the case of Twitter pushing off Meerkat to promote its own streaming service, Periscope. Or, Google being fined $2.7 billion by the EU in 2017 for abusing product searches. The list of such actions against ‘monopolistic’ players is long.

4. The nature of the relationship between the technology platform and the participants is vexatious. For example, a taxi driver is contracted and supposedly works on his own schedule. The hours of work are up to the driver or so it seems.

But in a ‘monopolistic’ situation, the driver’s schedule — days of work, hours of work, number of trips — and the concomitant disincentives and benefits are determined by the technology platform. What about employment benefits that a full-time regular organised job is mandated by law to provide? In a country like India, what are the implications?

5. The requirement of large sums of capital to create technology platforms means that Indian players are dependent on foreign money — typically Chinese, Japanese or American — to build their businesses. Given the nature of India’s regulatory environment — either an excess or the lack of it or the lack of enforceability, these Indian players are typically domiciled overseas in places like Singapore.

How should India think of this? With a large population coming online in the next few years and consuming enormous amounts of data, the dangers of data colonisation are real. How does one ensure that data security and privacy are governed and subject to Indian laws?

How does one ensure that Indian companies stay in India, raise as much ‘Indian’ capital as possible, and have Intellectual Property (IP) that is based in India? How to encourage Indian companies that are pygmies in comparison to global majors that operate in this new world?

6. India has used technology platforms as ‘public goods’, India-owned vehicles for social transformation that include direct benefit transfers, easy payments, democratisation of credit, bank accounts, healthcare, e-KYC/e-sign, electronic storage of records, travel and logistics. Aadhaar, Goods and Services Tax Identification Number, Jan Dhan Yojana, Unified Payments Interface, BBP and DigiLocker are some of these public goods.

This is in contrast to how other countries like China (state-mandated and owned) and US (private company led with the US government in the background). In November 2018, Reuters reported that “MasterCard told the United States government in June that Prime Minister Narendra Modi was using nationalism to promote the use of domestic payments network RuPay, and New Delhi’s protectionist policies were hurting foreign payment companies...”

How does India balance its sovereign interests with pressures from foreign governments and companies? How does India take this idea forward more deeply within India and to the rest of the world?

The rise of technology platforms is inevitable and rather than resist it, we need to evolve policies that can harness them for our benefit and protection, both for domestic as well as for strategic overseas initiatives.

It is imperative, therefore, for our policy makers, regulators, academics, think tanks, companies, media and aware citizens to come together for this purpose.