Learning And Openness

Mainstream technological and management education is founded on predictability, measurability and objectivity. In this context, it may be valuable to recall Tagore’s bold experiment with Visva Bharati.

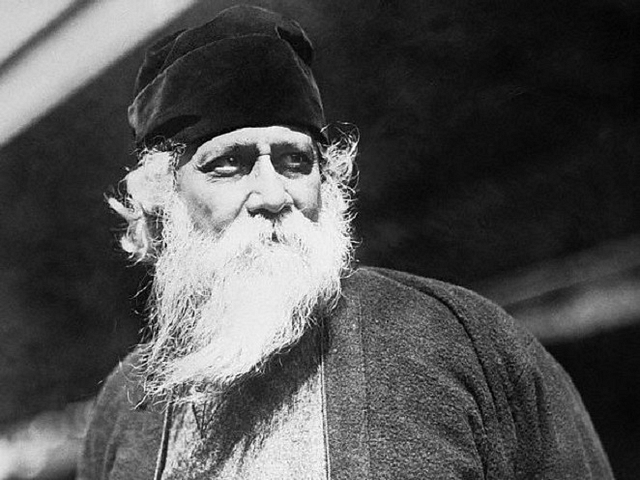

It is the opening scene of a documentary on a genius. A cortege proceeds to a burning ghat for the last rites of funeral to be administered. One can see the body of a bearded old man lying in state carried on their shoulders by devotees and accompanied by thousands of others. In the background, one can clearly hear the unmistakable baritone voice of the director.

“On the 7th of August 1941, in the city of Calcutta, a man died. His mortal remains perished but he left behind him a heritage that no fire could consume. It was a heritage of words and music and poetry, of ideas and of ideals. And it has the power move us, to inspire us today and in the days to come. We, who owe him so much, salute his memory.”

There have been several documentaries made on various aspects of the life and work of Rabindranath Tagore, but this film creates an indelible impact on our minds as the maker of the documentary is Satyajit Ray, another multi-faceted genius.

A significant part of the documentary is dedicated to highlighting Tagore’s unique and novel experiments on education. It begins with the child Rabi going to school. Ray poignantly depicts the disenchantment of the young boy in school. We see a classroom situation with some students and a faceless teacher. But we can hear a hackneyed mechanical voice speaking to the students in a manner that is a sordid example of rote learning. The exchange of words was like this:

Teacher (in a loud and monotonous tone): “Can you see a pot?”

Students (in a mindless cacophony): “Yes, I can see a pot.”

What was young Rabi doing when this lifeless teaching was going on? The shot portrays Rabi looking out of the window of the classroom. Far from participating in the rote learning exercise, he is intently watching and enjoying the colourful and rhythmic movements of Nature—the birds flying, the wind blowing and the water flowing. With rapt attention he was sipping in the elixir of life from Nature, least interested in the apology of a learning process going on inside the classroom. The air inside the classroom was heavy and stagnant, the light of knowledge groping in darkness, this young harbinger of futuristic education was looking out of the window for fresh air and new light. Nothing seemed more fascinating to him than the world outside. He attended four schools and hated them all and finally had his education at home.

Ever since his childhood, marred by systemic educational processes, this sense of “the other” haunted and also inspired Tagore to explore newer avenues of learning and living off the beaten track. This is something that comes as a striking blow to the very roots of the diehard proponents of professional education who champion the cause of “the one and the only way” to excellence, nay, success in life by pursuing higher education as in engineering or management. Just think of this: Tagore was sent off to study Law in England and guess what he learnt there? He came back without completing his studies but with a comprehensive knowledge of western classical music that would find abundant experimental adaptations in his future creative musical journey.

When he was sent to manage the family’s ancestral estate in Silaidaha on the bank of the river Padma (presently in Bangladesh), he would often spend time sitting in his boat and watching the myriad moods of Nature and the life of people in the rural milieu. The raging waters of the river and the vast open sky expanded the mental horizons of this ever lively spirit. This would later find expression in all his future endeavor to create “not this” but “the other” content or form of expression because he would always keep his options “wide open”.

The most significant achievement of Tagore in this search for “openness” and “otherness” was the creation of his beloved institute of higher learning—Visva Bharati at Shantiniketan in the district of Birbhum in West Bengal. This was to be his novel experiment in the open space in the lap of Nature far from the madding crowd of the metropolis of Calcutta. He made it abundantly clear to the students that they would have to learn from their teachers in person as well as the trees around. This way, he modeled his institution with inspiration from the “tapovan” or forest schools of ancient India where classes would be held in the open fields under the trees.

Observation of and living contact with Nature were integral parts of the learning process. Intimate daily relationship with the teachers in the institute environment was essential for holistic education and all-round development. Teachers and students participated in this novel venture, not just from India but different parts of the world. Here we have a classic example of a global mind with local roots in Indian culture and heritage. Tagore’s education was a synthesis of the East and the West, a bridge between ancient and modern culture, between the rural and the urban milieu.

His lifelong quest was to remain out of the rut from his schooldays in search of something new. He built five houses in Santiniketan but never lived in one of them for long. Even in one house, he would keep on changing the room where he would be staying in.

At the ripe age of 70, his creative spirit found a completely new expression—painting. And when he painted, he broke away completely from the established Indian tradition of art. His paintings are surreal, subversive and derived from the sub-conscious rather than from how an object or a person appears to our mundane eyes. It was all driven by his quest for “the new”, the “different”, “the other” all through his life.

What then are the key lessons from Tagore for modern education in management, or otherwise?

The dominant mainstream of technological and management education is founded on the pillars of predictability, measurability and objectivity. It creates an aggressive mindset among both the faculty and the students that there is one and only one solution to any problem. Moreover, the nature of the solution must be based on techno-economic rationality. No wonder, Viktor Frankl, the Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, in his insightful book Man’s Search for Meaning, had clearly diagnosed that the problem of modernity is not nothingness but “nothing-but-ness”. This captured the cocksure attitude of the techno-managerial mind that there is no space for “the other” or alternative solutions to any particular problem.

We tend to forget that there are intricate social, psychological, cultural and human dimensions to any problem—technical, managerial or otherwise. Even though courses on these dimensions are introduced in the academic curriculum, the mainstream stalwarts and consequently the bulk of the student community treat these as “soft” or irrelevant courses that hardly deserve any worthwhile attention.

This leads to building organizational cultures devoted solely to the pursuit of profits, turnover and economic expansion. Such organizations turn out to be engines of manipulation and exploitation that tend to disregard the finer qualities and sensibilities of man and the deeper human aspirations beyond money, power and fame.

The architecture of these organizations and educational institutions make them completely divorced from Nature. Tagore’s experiment on holistic education based on learning in the ambience of Nature comes as a bold and powerful challenge to such mindless behemoths that keep on churning out millions of One Dimensional Man (the title of book by Herbert Marcuse) devoid of heart and soul. We often forget that many of the management theories and practices we learn from the West evolved out of necessity in a spectre of human destruction and genocide—the Second World War.

It was the 80th and the last birthday of Tagore at his “abode of peace”—Shantiniketan. The poet was then a broken man with all hope lost in the spirit of humanism and glory of western culture and civilization. On that occasion, in the darkness of anguish and disillusionment and yet groping for the last streak of light, the poet wrote the essay Crisis of Civilization, his last testament for humanity.

This is how he concluded the masterpiece: “I had once believed that the springs of civilization will issue from the heart of Europe. But today, when I am about to leave the world, that faith has deserted me. I look around and see the crumbling ruins of a proud civilization strewn like a vast heap of futility. And yet I shall not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in man. I shall wait for the new dawn, a new chapter in history when the holocaust will end and the air will be rendered clean with the spirit of service and sacrifice. Perhaps that dawn will come from this horizon, from the east where the sun rises.”

Thought leaders in management academia, business leaders who often swear by western theories and practices, are we listening? Do we have any responsibility towards humanizing the disciplines of knowledge, including management, that will offer alternative sources and methods of learning to the West and others? When will the sun rise in the East?

The author is a Faculty of Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility at IIM Shillong. He has been invited to speak at several prestigious forums—the Aspen Institute, the Oxford Roundtable, the Global Ethics Forum (Geneva), and International Wisdom Conference at CEIBS, Shanghai, among many others. At IIM Shillong, he is the Chairperson of the Annual International Conference on Sustainability.