Living Off The Poor

For anyone wanting to understand the dynamics of poverty and take on the poverty-wallahs, armed with facts, this is simply essential reading

There is probably no other debate in which only emotions reign as that on poverty. Facts, statistics, logic are all cast aside as the poverty industry insists that the scourge has not been contained at all and that liberal economic policies and globalization are to blame for this.

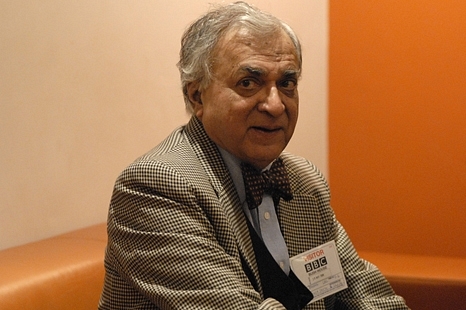

And yet there are a few brave people who dare to challenge this narrative. One of them is Deepak Lal, the iconoclast economist who has a sizeable body of work on poverty. His latest book sees him punching holes in many of the cherished beliefs of the poverty industry. He insists that “the end of world poverty is no longer a chimera. It is within reach”.

Lal makes a distinction between three kinds of poverty—structural (arising from the way the economy develops; this is ubiquitous), destitution (when individuals are not able to fend for themselves), and conjunctural (circumstantial or arising from specific events like famines or trade cycle slumps).

The book’s central message is simple—that rapid economic growth coming from following classical liberal economic policies alone can speedily bring down structural poverty and address destitution. The alternative approach—distributionist egalitarianism—only leads to the creation of what he calls a vast transfer state.

Lal asserts—using data to devastating effect—that there was significant reduction in poverty during both periods of globalization—the 19th century and the current period starting in 1980. “The highest yield in terms of poverty reduction has been since 1980, when the Third World started to integrate with the world economy.” Africa, he notes, is the least integrated with the world economy and is also the only region where poverty has not declined.

As for conjunctural poverty as well as destitution, income transfers are the only solution. But for Lal, income transfers are not necessarily government doles. The section on private transfers versus public doles is perhaps the most interesting part of the book. Lal shows that societies always had income transfer mechanisms—marriage, kinship, caste/community groups and the like—which were focused and well-targeted; only the really needy got them.

These more efficient private transfers have, he argues, been crowded out by the more inefficient public transfers. He quotes two studies to buttress this—one he did in India showed that for every rupee of public transfer, 56 paise of private transfer was crowded out. Another study in the Philippines showed that if a public programme were initiated to bring every poor household up to the poverty line, after adjusting for private transfers, 46 per cent of urban and 94 per cent of rural households will remain poor.

From here, Lal goes on to take on the international donor community. Foreign aid, he says, has created a worldwide poverty industry and has not eased poverty anywhere. Money given for the poor never reaches them; it is stolen by influential elites in recipient countries: “Whether or not there was ever a time for foreign aid, it is an idea whose time has gone.”

In the second part of the book, Lal sets out to demolish the myths surrounding poverty. He exposes the political intrigue of poverty numbers put out by the World Bank and its fraternity, which seek to exaggerate the extent of poverty incidence and understate the extent of poverty alleviation. Questioning the purchasing power parity (PPP) databases which are used to measure global poverty, he says the professional rectitude of international agencies cannot be taken for granted, given their politicisation. Particular mention is made of a PPP adjustment in 2005 which downgraded the PPP value of most Asian economies by 40 per cent, resulting in their poverty numbers being higher than in 1993.

The climate change lobby also gets its share of flak. Why is that part of a book on poverty? Lal insists that the campaign on global warming is “the greatest threat to the alleviation of the structural poverty of the Third World”. Here again, Lal is not ranting without basis. He goes into the science, economics, politics and ethics of climate change, looks at climate change estimates by the IPCC and shows how there is a deliberate attempt to create a needless scare. R.K. Pachauri, the now-disgraced head of the IPCC, gets more than a rap on the knuckles for some alarmist statements on Himalayan glaciers which he was forced to retract.

Some chapters are slightly tough going for non-economists. But for anyone wanting to understand the dynamics of poverty and take on the poverty-wallahs, armed with facts, this is simply essential reading.

This piece appeared in the June 2015 issue of Swarajya