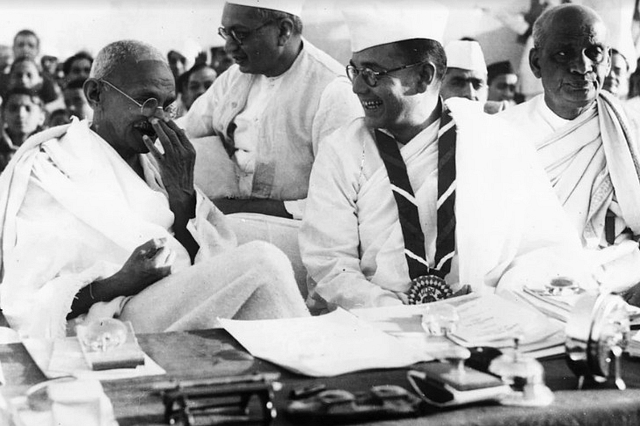

Sardar Vs Netaji

In the late 1930s, Sardar Patel faced a battle on many fronts. Within the Congress, his fiercest contest came from Subhas Chandra Bose.

The Man Who Saved India: Sardar Patel and His Idea Of India. Hindol Sengupta. Penguin Viking. Hard Cover. 437 pp. Rs 799.

With each passing day, as the Congress fuelled more citizens committees in various princely states, the collision course between the Sardar and the rajas and maharajas was set. In Rajkot, matters got so out of hand that, afraid of the democracy that the Congress sought to bring to the people of the state, the rulers spread word that Patel and Gandhi were out to crush the rights of the minorities, including Muslims. It was here that Patel first faced the combination of an eccentric ruler who had squandered the wealth of his kingdom and his crafty diwan who did whatever it took—including raising cruel taxes on farmers and pawning off every last public asset of the kingdom—to keep the prince on the throne (and the diwan in power). This theme would be repeated in a much more definitive scale in Hyderabad a few years later where, no doubt, the Sardar remembered the lessons of Rajkot and dealt with the administration accordingly.

In the case with Khare, and then again at Wardha, we find instances of how the narrative of Patel being against minorities was maliciously built and spread. The Khare issue blew up when, as the premier of the Central Provinces, the Congressman allowed his Muslim law minister to release four Muslim men convicted of raping a thirteen-year-old Harijan (Dalit) girl. An incensed Patel wrote to Bose, the party president, that ‘it was a most heinous offence’.73

In Rajkot, the situation turned venomous and armed crowds attacked a meeting Gandhi was addressing, looking to kill Patel. Pandals of Congress meetings were burnt, and later, in one incident, at least one Congress worker was killed trying to save Patel when a meeting was attacked by a Muslim mob. These were not the only instances of violence the Congress was facing from some Muslim communities. In September 1937, Prasad wrote to Patel about the violent reaction of some Muslim groups towards ‘Vande Mataram’, the revolutionary song of the freedom movement, and even the hoisting of the national flag that the party had decided upon leading to bitter clashes in many areas in Uttar Pradesh.

"I have seen that in some districts the Bar Associations have passed resolutions for hoisting the flag on their buildings in the teeth of opposition from the Musalman members who being in the minority have walked out in protest [. . .] Similarly, the Bande Mataram song is objected to by some Musalmans on the ground that it is invocation to Hindu goddess and in terms it means idol worship which Musalmans can never agree to."

Even though Prasad readily admitted that not all Muslims felt this way, his overall impression was that there was problem in this regard both with the song and also the national flag.

"While there are Musalmans who do not look upon the song in this light, there is no doubt a feeling among them not to accept it as National Song just as many of them do not accept the tricolour as a National Flag."

The roots of division were spreading and by June 1938, Patel would write to Nehru, saying, ‘Jinnah’s speeches were very bad. In fact, the impression left on the general public is that they [the Muslim League led by Jinnah] do not desire to have any settlement at all.’

Faced with such violence Gandhi stepped back from aggressively pushing democracy in Rajkot, and protests were fuelled by local rulers in other states.

All of this gave Patel, and the Congress an indication of the enormity of the task of unifying a free India, but before that, they still had to deal with Bose who wanted a second term as Congress president. In spite of his reservations in March 1938, Patel had been asking Congressmen to support Bose’s presidentship but now his old misgivings reappeared.

If Patel had been wary of Bose becoming president for one term of the Congress, he had deep misgivings about Netaji having a second term. There are many issues that bitterly divided Bose on one side and Gandhi and Patel on the other. Bose, fundamentally, was sceptical of Gandhi’s leadership, having never quite accepted him as his leader, nor did he believe Gandhian methods to be the inevitable path for the Congress to take in the freedom movement. As early as 1928, at the Congress session in Calcutta, Bose had shown off his own cadre of young men and women whom he called the Congress Volunteer Force with their own ‘Bicycle, Cavalry and Coded Messages divisions. The troops paraded on the Calcutta Maidan early each morning under the eye of General Officer Commanding Bose, who dressed himself in breeches, aiguillettes and long leather boots. Gandhi disliked the Force’s paramilitary overtones, and complained about the saluting, strutting and clicking of heels.’

As Nirad C. Chaudhuri has explained:

“With the emergence of Gandhi’s leadership, there had also appeared within the Indian nationalist movement a clearly-felt antithesis with three aspects. First, Gandhi’s ideas and methods were set against those of the familiar Western type; second, the pre-Gandhian leadership was confronted by the dictatorial newcomer; third, northern India stood against the peripheral regions, such as Bengal, the Tamil country and Maharashtra. Gandhi, himself an extremist and fire-eater, was incapable of tolerating rival extremists and fire-eaters. His usual method of coercing others was to threaten non-cooperation, and such was the value set on his personality and ideas that the threat brought all potential dissidents to heel.”

As Bose became more and more popular, the differences in approach, if not ideology, grew even stronger.

"Nonetheless, a cleavage remained, and as time passed and Bose gained confidence and popularity, he came increasingly to symbolize the opposition to Gandhism. At his very first meeting with Gandhi in 1921, Bose had not been impressed, but at that time there had been no question of his pitting himself against the older man, whose leadership he had had to accept. Throughout his political career, however, Bose not only remained indifferent to the Gandhian way but also seemed to affect a tolerant superiority toward it."