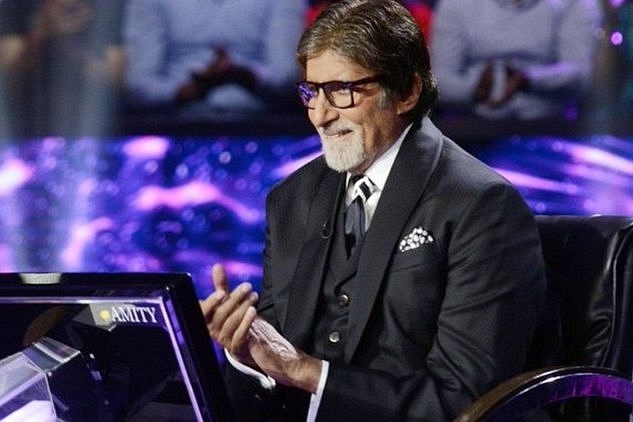

The Crore Of The Matter: How The Rupert Murdoch-Amitabh Bachchan Magic Made India ‘See Star’

In the year 2000, Star India was not much of a hit. Then came in Rupert Murdoch. After him, Amitabh Bachchan. What followed subsequently was KBC. And then, there was no looking back.

The Making of Star India: The Amazing Story of Rupert Murdoch’s India Adventure, Vanita Kohli Khandekar, Penguin Portfolio, 240 pages, Rs 427.

While they were still talking, late in February 2000, Murdoch senior came to town after four long years. And in a meeting that has now become part of corporate legend, he changed everything (See Prologue.)

He upped the prize money by about a hundred times, made it an hour-long daily show instead of a half-hour weekly show.

The name of the show then changed from Kaun Banega Lakhpati to Kaun Banega Crorepati. For most middle-class Indians, Rs 1 lakh or Rs 100,000 was a huge amount; it still is for large swathes of Indians.

A prize money of Rs 1 crore or Rs 10 million was something many of us would not save in a lifetime. Murdoch egged the India team on to bet big on getting the largest audience possible, beating the competition by a huge margin and then staying there.

By March 2000, the Star team had all the ammo it needed — a great idea for a show, plus Murdoch’s backing.

Getting the ‘Big B’ was proving to be difficult, however. Nair called Sunil Doshi, Bachchan’s agent, man about town and now a producer of some repute, and sent him the tapes.

“Amitabh didn’t have work; nobody wanted to work with him. The market thought he was finished and the family was against it,” remembers Doshi. “He was interested but he kept see-sawing,” says Nair.

Many meetings followed. Bachchan may have been down and out, but he was the equivalent of Marlon Brando or Al Pacino in India — not the sort of guy who would host a TV show.

Not just Bachchan, at that time, no Indian film star worth their salt would be seen on television unless they had given up on getting film work — it was seen as a step-down.

Bachchan was understandably ambivalent. Not surprisingly, the Aussie and English expats in Star’s Hong Kong office couldn’t understand why Bachchan was thinking twice —Hindi cinema was not yet the global force it was to become in the years to come.

Nair was adamant on Bachchan, and even Mukerjea, who had no feel for Indian cinema, knew that getting him would make the big difference.

He went along with Nair’s judgement. But they were already in April. James was keen on closing the deal so that Synergy could start with the rehearsals and Star could launch its flagship show announcing its Hindi avatar soon.

In the process of convincing Bachchan, Nair, Siddhartha, Doshi, Deepak Sehgal, Ravi Menon (part of the programming team) and Dutta took him to London to illustrate what the show was about.

Bachchan spent a full day in Elstree Studios on the sets of the UK version of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire, which was being hosted by Chris Tarrant.

He saw for himself the drama, the scale and the involvement the show created. That evening, Bachchan met with the rest of the team in a suite at the St James’s Court hotel in central London, where they were all staying.

Here is how Siddhartha relates what happened next. Bachchan was quiet for some time. Then he turned to Nair and asked, “Can you do it exactly like the Brits?”

Nair turned to Siddhartha. “My worry was whether the stakeholders would wrap their heads around what was involved. The technology, the telephone issues and the participants — those were my problems. We used to handle very complex shoots on shoestring budgets. So, we could do it, but “if you give me the resources”, I told Sameer. And Star pulled out all the stops.”

Bachchan signed on in April, three months after Nair had first approached him. It was the same month that I had the interview with James and Mukerjea.

Another big effort lay ahead to fulfil the promise of the show and the one made to Bachchan and Siddhartha — putting together the back end for KBC in India where production standards were far from world class and infrastructure was wanting.

The KBC format with its call-ins, SMS voting et al needed a backbone and IT infrastructure that could take a certain load and could be scaled up. It needed intelligent lighting, continuous electricity — things that were not the norm in India.

In April 2000, India had just over 32 million landlines and maybe a couple of million mobile users against over a billion now.

A lot of work went into meeting the right people in the government and in telecom companies so that a good back-end could be set up. Synergy’s team relocated to Mumbai from Delhi and a team of about 250 to 300 people started working on KBC.

The sets (designed by ace set designer Nitin Desai), the floor lighting, the chair, the computer — all of it — was put together according to the bible that Celador provided and was of a quality that Indian audiences and even the crew had never experienced.

The team was right to worry, worry, worry. When the phone lines opened, the per day call volume was over 150 per cent of what the system was designed to handle.

An estimated 1.2 million calls were received before shooting for the show began at a specially constructed set at Mumbai’s Film City in June 2000.

When Bachchan entered the set on the first day of the shoot, all the lights went off. There had been a big technical fault somewhere and all of Mumbai was on the blink. After a wait of three hours, the shoot was cancelled. “Amitabh thought it was a bad omen,” remembers Doshi.

It was probably some of the residual bad luck that Star had had in India. When I asked James how Star could hope to catch up on nine years of being a laggard, he said, “We did lose a lot of momentum and were hindered terribly because of our partnership with Zee. The restriction on Hindi-language programming was ridiculous. We got out of it at the end of January this year [operationally]. Now we have been going full throttle to build our Hindi programming. I think with the investments and management Peter is putting together, their heads are just going to spin. Sony and Zee won’t know what hit them.”

They didn’t.