The Nectar Overflows

This fine book gives us a peek into India’s vast stack of bhakti poems, and a sense of the elements that bring together its people as one.

Love And The Turning Seasons : India’s Poetry Of Spiritual And Erotic Longing. Edited by Andrew Schelling. Aleph Book Company. 2018.

We are yours for life.

Make all our desires be for you,

It is you alone that we want. Hear our song!

— Andal (Ninth century, Tamil)

Spirituality, expressed in multitude shades of love for one’s chosen god — from contemplative reflections to rapturous ecstasy — has been a part of India’s treasured heritage. Spiritual poems were often intimately devotional, sometimes philosophical, abstract, even disdainful towards piety, and without much of logic or rationality. And this love was not confined within any social strata. The poetry of spiritual and erotic longing sprang as much from the hearts of commoners as from within royal palaces.

Love and the Turning Seasons; India’s Poetry of Spiritual and Erotic Longing, put together by American poet and translator Andrew Schelling, is a compendium of poems from a variety of Indian poets who demonstrate bhakti in a variety of ways. “Bhakti”, a word that is instantly recognisable all over India — what imagery does the word paint in the mind? That of extraordinary devotion, pure love, and surrender to one’s chosen god? Revealed through intimate and impassioned compositions? Schelling’s anthology presents such creations from much of India. Thumbing through the pages, the general reader can soak in the unabashed, naked pronouncements of love — the experience, both exhilarating and unsettling. The book is proof to the fact that in India, love or devotion did not conform to just one notion.

Starting with the Isa Upanishad and a few ancient Sanskrit hymns, the book journeys through the land — going clockwise with lyrics from the southern states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, with a little bit of Kashmir amidst them! — to the west, covering Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, traversing to the north with songs from Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, then going east to Odisha, Bihar and Bengal. Kerala and the northeast states are conspicuous in their absence. Schelling manages to trace the timeline too somewhat, starting at ninth century Tamil Nadu and culminating in twentieth century Bengal — almost following the pattern of the spread of the bhakti movement itself.

The Isa Upanishad stanzas are perhaps the most abstract. The use of the neutral pronoun for the great one, addressed as “poet, and thinker”, sets them apart.

All objects

have in their self-nature

been arranged precisely about us

by that presence —

poet, and thinker.

— Isa Upanishad (circa 600 BCE, Sanskrit)

The pages overflow with diverse articulations of love — there is the acute passion of Vidyapati —

“With the last of my garments

shame dropped from me, fluttered

to earth and lay discarded at my feet.

My lover’s body became

the only covering I needed.”,

the anguished pleadings of Mahadeviyakka —

“But how can I bear it

when He is here in my hands

right here in my heart

and will not take me?”,

the reckless honesty of Kabir:

“Not one, not two,

but everyone’s a sucker,

says Kabir. Not me.’’,

the youthful earnestness of Bhanusimha (Rabindranath Tagore),

“How long must I go on waiting,

under the secretive awning of the trees?

When will he call the long notes of my name

with his flute: Radha, Radha, so full of desire

that all the little cowherd-girls will start awake

and come looking for him, as I look for him.”

The notes include profiles of the composers and their legendary lives — much of which is hearsay, folklore, almost mythical, like the disappearances of Adtal, Mirabai, Muktabai, Lal Ded — their bodies being absorbed by the gods.

The compositions are sensational, almost taking your breath away, so blatant are they in declaring their intent. Did the poets not want to keep some of their desperate yearnings private, deep inside their hearts? What made it possible to brazenly proclaim their cravings, erotic or otherwise, with a starkness that is almost impossible to find in our everyday lives?

“Drape my loins with jeweled belts, fabric and gemstones.

My mons venus is brimming with nectar,

a cave mouth for thrusts of Desire.”

— Jayadeva in Gita Govinda (Twelfth century, Sanskrit)

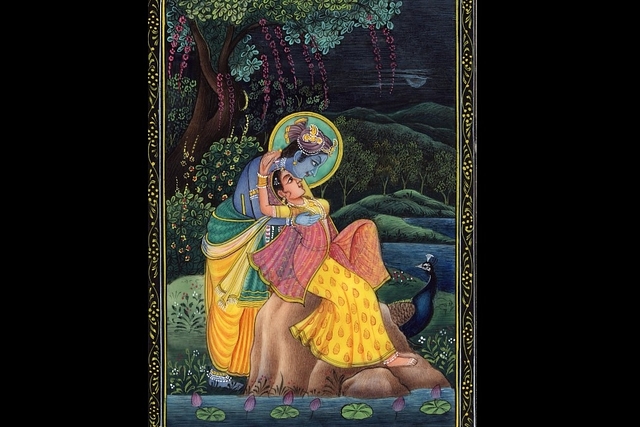

Lying at the heart of these verses is an individual’s unique relationship with god. Typically, the swooning over and losing oneself are for Krishna — whether the poet is a man or woman, the pining for Krishna is in the voice of a young woman. The idea that recurs through the pages is that the phases of human love are metaphors for the phases of mystic ascent. Whether or not one can wrap one’s mind around subtle doctrine, everyone can taste the despondency and euphoria of love, and this is where one finds Krishna.

The love making of Krishna and Radha is equalled to the self’s actual union with god. How gloriously simple!

When they had made love

she lay in his arms in the kunja grove.

Suddenly she called his name

and wept — as if she burned in the fire of

separation.

The gold was in her anchal

but she looked afar for it!

— where has he gone? Where has my love gone?

O why has he left me alone?

And she writhed on the ground in despair,

only her pain kept her from fainting.

Krishna was astonished

and could not speak.

— Govinda-dasa (1535 - 1613)

Many of these songs still live amidst us — Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda continues to be played at the Puri Jagannatha temple, Andal’s ninth century Tiruppavai is chanted to this day in Tamil homes during the month of Margazhi, Bengali Baul singers and Bob Dylan came together in New York to make music, Lal Ded’s fourteenth century vakhs are sung by Kashmiris even today.

But while Schelling seems to be completely in touch with India’s poetry, he seems out of touch with India, and this comes through in little details. For instance, he asserts that Brajbhasha is no longer in use, when in fact you will hear it in some mainstream Hindi movies, and even find it on YouTube. It is still a spoken tongue in many a Brajbhoomi home. Or when he wonders why Akho of Gujarat remains virtually unknown to those who do not speak Gujarati, and finds it ironical that the state of Gujarat has a population larger than England! If the rest of India is not familiar with Gujarati, how will it know a poet who composed only in Gujarati?

He mentions that historians surmise that Krishna is an indigenous deity, not an “import” brought to India by the Indo-Aryan settlers. Were India’s other gods brought by “outsiders”? Considering how often the theory of Aryan migration is disproved, it is amusing to see the narrative of the Aryan outsider.

That said, to get a peek into India’s vast stack of bhakti poems, and to get a sense of the elements that bring together its people as one, Love and the Turning Seasons is a marvellous, compact, finely laid-out book.