The Sympathetic String Of Two Traditions

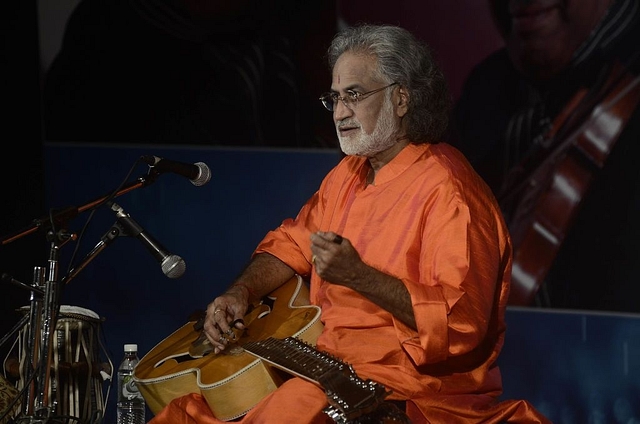

Pandit Vishwa Mohan Bhatt opens up on Margazhi, the genesis of his Mohan veena, and how he weaves his way through the most brilliant musical collaborations and continues to lead.

Jaipur-based world renowned musician and propagator of the Mohan veena, Pandit Vishwa Mohan Bhatt shot to fame for his Grammy winning album A Meeting By The River with renowned guitarist Ry Cooder. The album was recorded by Water Lily Acoustics in 1993. But even before the prestigious and one of the most cherished awards, the Grammy, came his way, Bhatt was a respected musician, who was carving out his own journey into music, with blessings from his guru Pandit Ravi Shankar. That the Grammy came to an Indian the third time, then, did matter a lot to lovers of music. That it came to a guitar virtuoso, who was known for creating magic with an instrument converted from an ordinary acoustic guitar, turned minds and ears to his brilliance and experimentation in sound and composition.

It set off a faster unstoppable journey around the world, where Bhatt would emerge as the leader of collaboration, in world music, conversation between cultures and influences, and the least hyped – jugalbandis with the musicians’ representation of the Carnatic tradition. In all his collaborations, one quality that stood out in his music was his sensitivity to music on the whole. It propped up, naturally, his sensitivity to his co-artistes, their music, cultures, skills, talas and musical treasures. It raised, most beautifully, the standard of collaborations where artistes, quite freely, responded to Bhatt’s own freedom with his musical instrument. From some of these recordings, it is clear even today, that Bhatt was navigating in freedom, not caring (much) what the Western audience would approve or applaud for.

One of the leading musicians in India, Bhatt is known to have squeezed the best out of the structural technicalities of his musical instrument. There is the best of a few worlds in his musical instrument. It a bit of East, a bit of West, a bit of his own added to the confluence of these two. There is the tantrakari aspect of the sitar, with sympathetic strings defining the sound, its quality and the interplay between tuning and playing, and the gayaki ang, which involves largely his own explorations as a singer concealed within a musician. The vocalist in Bhatt, as evident from his collaborations with a wide range of maestros, musical instruments and styles, responds with essential alertness to Carnatic music.

It was in the month of Margazhi, that I discovered several new dimensions in Bhatt’s jugalbandi and his approach to gayaki and layakari, the first time. These dimensions came into play, perhaps, owing to the fact that he was celebrating music in south India. At the concerts I attended, Bhatt was performing with Chitraveena N Ravikiran. These aspects, mostly pertaining to his response to a different veena and its own sound and tradition, were largely unexplored in the north Indian set-up or foreground. Bhatt and Ravikiran, like any other genius collaboration, had built a language of their own. Improvisations would strike out from their veenas like lightning without the thunder – brilliant, striking, but soft. Bhatt’s conversation with Carnatic music and musicians, that has involved some of the greats in the field, continues. It is at the core of his Bharatiyata.

Here are excerpts from a conversation with a musician, who still learns from the Carnatic tradition while continuing to be the leader of world collaborations.

What fascinates you about the Carnatic tradition and the celebration of music during Margazhi?

What I find very unique about the celebration of music in the month of Margazhi is that it lasts a month. A month for the celebration of music, in itself, is unique. The musicians and the audience, both, are deeply rooted in tradition. They do a lot for the prachar prasar (popularity and propagation) of their music. The audience is wise and informed. They understand the intricacies of music and composition. They understand the most delicate nuances of music. One of the most fascinating aspects of performing in the south or for an audience that understands Carnatic music is that they all are completely involved in what they hear. Sab taal lagate hain (they all follow the rhythmic cycle and display the rhythmic cycle in a play of hand as they listen). There is complete involvement. Here, in north India, things are very different. The audience is not involved to the extent it is in the south. In the south, you know as an artiste that the audience really understands what you perform and what they hear.

I like the audience in Mysore (Mysuru). It is distinctly traditional. Recently, I performed four times in Chennai in a short period of time, and it has always been a very good experience.

Recall some of the memorable duets with artistes from the south.

One of the most memorable concerts and collaborations with artistes from the Carnatic tradition has been a performance with renowned flautist Dr N Ramani. Vidwan Vikku Vianayakram and Ustad Zakir Hussain were performing with us on the ghatam and tabla. It was a very exciting performance and gave us brilliant music on the spot. Then, there is an unforgettable duet with M Balamuralikrishna ji. Duets with Ravikiran, and several noted violinist such as M S Gopalakrishnan, Vidwan Lalgudi Jayaraman, L Subramaniam, Mysore Manjunath, Ganesha and Kumaresh, have been spectacular.

What sets off collaborative work with artistes representing the Carnatic tradition?

Carnatic music tradition has a galaxy of wonderful musicians. Veena, in its traditional form, in itself, is a very popular musical instrument in the tradition. Each musician has a distinct style of playing the veena and listening to every sound, and a different playing style is a deep musical revelation to experience. When I am performing a duet, I give my co-performers a field to play. Mostly, I have to adopt a field when I give them one. They are all musicians par excellence. To witness their individual genius unfold, I have to create a field and make it more suitable for them for a great jugalbandi. I have to accommodate their music and they have to adopt mine. That’s required to make one music. To make music together. It is what happens when I am playing with L Subramaniam or with L Shashank.

They all love experimentation like I do. Their love for experimentation shows in their musical instruments, in modernity with which they approach tradition, and in the structural changes they have introduced in their musical instruments. The modern reverb, pick-ups, etc, make the sound very exciting. They approach production with a forward-looking mindset. K Sathyanarayanan, the young keyboard artiste is a wonderful musician. I love his technique. Similarly, L Shashank. I am in my late sixties. But when I perform with these young and brilliant musicians, I realise what wonderful phrases get played in the process of making music. Especially, the tihais (where notes form complicated combination as per the raga to be played thrice to arrive at rhythm math).

Add to that the fact that Hindustani and Carnatic music are different characteristically in how they approach music and ragas. This aspect plays out really well in my musical interactions with them (musicians practising the Carnatic tradition). (Sings notes to make a meend – a bend using notes in a melodious slide). Ravikiran has a similar sliding technique yet, what he and I play is so distinct. The staccato notes are there, but there is an intelligent interplay between meends and gamakas. In Hindustani music, we prolong the note. We sustain it. In Carnatic, they go to the notes and cover them quickly. Then, both are covering a lot of notes in different ways, in jugalbandi and in ragam tanam pallavi. They do certain things which are not part of their music for my sake and I do a few things for their sake. This is adaptability.

You are the daring convertor of the acoustic guitar into the Mohan veena. Tell us how it started and where you currently are with the instrument.

It started in the late 1960s. Between 1966 and 1967, I made a Hawaiian slide guitar without any tarab (sympathetic strings). I needed the sympathetic strings like the sitar to arrive at the sound. They work as resonator. They vibrate. That makes sound very sonorous and sustained. I started putting them myself with a screwdriver. I did it myself. I could not go to any manufacturer and could not explain what I wanted. Then, I did find a manufacturer. He put seven sympathetic strings for me. My sister Manju had brought a guitar for me from Germany. Once, while returning from Germany, she asked me what I wanted. She got me a very costly guitar. I was lucky to have it with me. I put the chikari to it – like in sitar and sarod. I increased the number of strings on the front to eight. They are 12 now. So, there were eight strings on top. Three main, five drone strings, including the chikari (usually the last in sequence, used for finishing strokes on different stages of a composition sequence. I put a tumbi (a hollow made of gourd – for resonance) on the rear side – on the finger board to hold it properly. I played this version of the instrument for 14 years. Then, I went to Kolkata – the home for manufacturing sitar and sarod. The manufacturer gave my instrument 12 strings. It sounded so well. The previous version had a strong and thick body. I told him to use very thin ply. The experiment was successful. I played that instrument for 28 years. The time period included some prominent recordings.

I was flying from San Francisco to Mumbai. My instrument was broken, almost smashed in the aircraft. It was completely irreparable. I flew to Calcutta (now Kolkata). The instrument had to be made from scratch. This time, here, I got an idea to put a pick-up in my veena. The breaking of my instrument came as a blessing in disguise. This instrument was my dream sound. I could get everything in this veena. There was a gradual development of sound.

Now, I have reverb in the Mohan veena. There is a system where I can play three octaves in one stroke. We should aim for the sound control and quality we deserve instead of what the sound system guy has to offer. We know the tone we want from our instrument. I have my own equaliser with me. And I face every music system quality by adjusting the sound. I get the best out of the worst music system.

In the early 2000s, Mohan veena and Vishwa veena, two of your musical instruments got patented. Which instrument is your love?

Both Mohan veena and Vishwa veena are under my name. Vishwa veena has 35 strings – 20 of Mohan veena and 15 of swar mandal. The magic of the swar mandal can be seen in the way it gives Pandit Jasraj all the moods. It gives flow. Vishwa veena, hence, owing to the presence of two musical instruments in one, and the way it is played, gives the feeling that there are two artistes playing one single instrument. It sounds great, but Mohan veena is my first love.

How did your guru Pandit Ravi Shankar help you explore the Mohan veena and music?

It was in the early 1980s that I found a guru to surrender my music to. Pandit Ravi Shankar told me that you have Indianised the guitar, and in a wonderful way, it will be my pleasure to teach you. For me, it was a dream since my childhood, to be a good artiste and he was my idol since my childhood days. “Artiste ho to aisa.” There was immense respect for him. The applause he received for his music would make me wonder and dream, that someday, even I will see myself being respected and receiving applause for my music and art. Sometimes, we feel like surrendering to someone. For some people, it is a guru, for some, a parent, for some, a girl and so on. For me, it was a guru. That sense of surrender was in mind. I knew that the raag sadhna I had in me, I will dedicate it to Pandit ji. Learning from a guru like Pandit Ravi Shankar was learning in a very different manner. With guru ji, sometimes, to be learning from him, you don’t have to learn only while sitting, or in a learning session. Learning would be done in conversations and discussions. In his talks.

Pandit Ravi Shankar was a punctual man, artiste and guru. He would arrive 15 to 20 minutes before a lesson — for his disciples, ready with his sitar, everything organised and in place, including the agarbatti. At the sessions, he would be the complete guru — dedicated, focused, punctual. He would teach the intricacies and dos and don’ts of each raga. Even in an aircraft, he would tell me the raga swaroop, and the combinations. I knew the boundary of each raga to play, to play authentic music. To learn that authentic way of playing the raga, a guru is necessary. I was fortunate to have him as my guru. Sometimes, he was strict. Very creative. Brimming with improvisation. He was so quick in making new tihais. He used to compose complicated layakari tihais. He used to leave the sthai for us — to be worked upon by us. “Work on it”, he would say. He was like a true living god to me.

Technique wise, the sitar is a great instrument. My instrument approached the gayaki ang more than the tantrakari ang — the strength and speciality of the Maihar Gharana. Pandit ji said play what is suitable to your instrument. He told me to just improvise as per my instrument.

That you met renowned guitarist Ry Cooder barely half an hour before sitting down to record, what would be a Grammy winning album, surprises people. How did it happen and lead to other popular world music collaborations?

Collaboration with musicians from the West started in America. The collaboration with Ry Cooder was a great start in this journey. It was for Water Lily Acoustics, an American record label. It promotes the original sound of the instrument. They approached me and said that well-known guitarist Ry Cooder has heard me. The collaboration began. We started a recording at midnight. It was a hectic schedule at my end. We sat down to play. I came into a mood. A Meeting By the River was born. Three more tracks were recorded. It was a short album of only 39 odd minutes. I believe not sufficient for a record — going by the popular norm, as listeners expect at least a 60-minute record. During those times, people wanted more. They still sold it taking a risk. It did well. I think it won the Grammy and hearts because it respected the sound. We found the tone. Meeting By the River is raw. All original sound. It was highly appreciated. It is directly from art. We had not rehearsed it. Those parameters worked. It won the Grammy for the purity and originality.

After this, was a jugalbandi with a Chinese ehru player Jei Bing Chang, American dobro guitar player Jerry Douglas, with Arabian oudh player Simon Shaheen. The collaboration with banjo artiste Bela Flek, ‘Tabula Rasa’ and erhu master Chang got nominated for the Grammy award in 1997. The collaborations and travels are continuing. I have visited 80 countries so far, and I hope I make more and more music and continue the work of propagating the Mohan veena and Indian music across the globe.

How do you approach collaborations, especially those with artistes from outside India?

I directly learn from their art and their mind. We learn from them. They learn from us. One has to keep digging more and more into ragas. If you become stagnant, you yourself will become bored. I am playing Yaman Kalyan for five decades. That is the interesting part in our music. With creativity and re-imagination, the music matures. It develops and improves. The path opens for good jugalbandis. No surprise people wonder how Indian musicians delve into the same ragas again and again. How do you do this, they ask. What is he doing at just one spot? They wonder, sometimes, when they find me mulling over the same note for long.

I use the scale changing system to give them the field to play. In this system, I stay at my shadaj and change it for them, and keep changing it for them. This way, I make them move and shift from, say, Bhupali, to Bhairavi, without having them to really make any changes to their music.

Arabian music has makaams, and you can identify scales. We know these scales by names — Bhupali, Bhairavi, Malkauns, and so on. Then, in Japan and China, there are popular scales, which sometimes are the only option to record an entire collaborative album. How do I go with the single raga for the entire album? I would apply my mind. It was tricky. I used the scale changing system. My sa (shadaj) remained my sa. Their sa changed (when the scale was changed). ‘You play the same thing’, I tell them. It becomes a different raga by changing the scale. I play — according to my sa, they play according to their sa, — and there — a new raga (laughs). What we call the Shadaj Madhyam bhav, you see. I apply that (laughs).

I give the co-musicians to play what they want. I compose according to their skill and taal. Indian musicians can do anything. We have all combinations, we have all the layakari in our system, all the taals. In our Indian music system, we have 72 melakarta ragas. If I give the co-musician something to play in staff notation, like Pandit Ravi Shankar wrote and gave an ace musician he collaborated with, it would take me seven days. For musicians, especially violinists, it is easy to sit and play a notation. Pandit ji was so brilliant that he remembered the staff notation he would get written by someone else for his co-musician, completely. He did not even have to look at the notation.

Which ragas excite you more?

Dharmavati, Hamsadhwani, Charukeshi, Kirwani and Sarsangi are always an essential part of my performance, whether solo or duet.

Vadya vrind (Indian orchestra) was flourishing during Pandit Ravi Shankar’s times. Would you want to revive it with the same vigour?

Vadya vrind has been a passion for me as well. Whenever I get the opportunity to combine with a veena ensemble, I happily accept it.

The veenas are our heritage. What can be done to pass them over to more and more hands and the next generation?

Saraswati veena has a tremendous sound and look. The rudra veena has a rare sound, and late Ustad Asad Ali Khan sahib has done a lot towards his instrument and its music. Ravikiran ji (Chitraveena N Ravikiran) has a unique playing style. I am particularly interested in the gottuvadyam and the vichitra veena, the batta veena. We have a great heritage of the veenas, and they should be propagated widely among audience in India and abroad. Recently, I have noticed that aspiring musicians like to watch veena videos. They see how the veenas are held, how they are played, how the different sliding material is used etc. I encourage them when they show me their videos. The Mohan veena is popular in America and students are learning how to play intricacies like alap and jhala. Some of my disciples, including my sons Pandit Salil Bhatt (who also plays the satvik veena) and Saurabh Bhatt (who is more into composing music) are doing well. Our music, the playing and teaching of the veenas, is their best propagation. I am doing my bit towards it.

Margazhi is a celebration of bhakti, tradition, spirituality and music. What is your view of Margazhi?

Bhakti and spirituality are one thing, I suppose. Music is the language of gods, and it is considered the medium to reach the almighty. South India has very deep roots for music and music traditions. In most homes, you will find a tanpura or a veena, or someone learning a performing art. Music is always an integral part of the lives of people in south India. I feel that music organisations and music academies such as the Narada Gaan Sabha, Krishna Gaan Sabha, Music Academy, Madras, and such, are doing great work in popularising classical music. The people are devoted to music. They celebrate the language of the gods. Margazhi brings one such celebration.