What Rajaji’s Swarajya Thought Of Nehru

Rajaji was the co-founder of Swarajya. Would the history of independent India have been different had Nehru listened a bit more to him than he did? The answer is Yes.

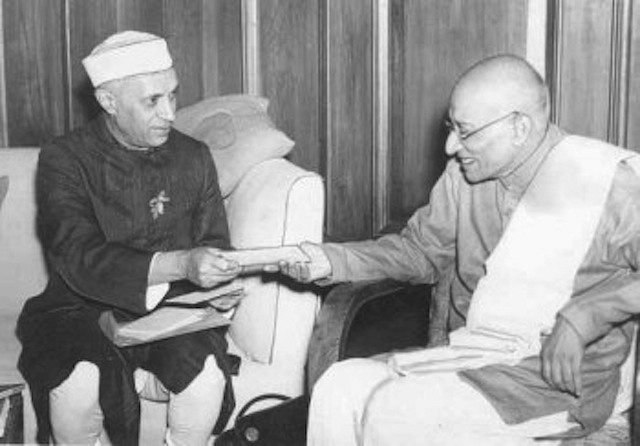

“Eleven years younger than me, eleven times more important for the nation, and eleven hundred times more beloved of the nation…” This is what C. Rajagopalachari “Rajaji” wrote in Swarajya when Jawaharlal Nehru died in 1964. Rajmohan Gandhi’s book on his maternal grandfather, The Good Boatman, also mentions how devastated Rajaji was by Nehru’s passing away—there is a very touching sequence about Rajaji condoling with Indira Gandhi at Teenmurti Bhavan, the Nehrus’ residence in New Delhi.

Even in the extremely vituperative political climate that currently prevails, political rivalries do not override personal courtesies. Rajaji’s words were well in keeping with that age, when politics was more refined and cultured. But this was not a pay-rich-tributes-on-death formality. Rajaji, who provided a strong liberal counter to Nehruvian socialism, truly believed his ideological opponent’s death was a loss for India. He said so often when Nehru was alive and at his peak.

When the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution on Kashmir which was widely seen as a rap on India’s knuckles, Rajaji ticked off those in the international community (and there were many) who were rejoicing at the so-called snub to Nehru. “The power that Jawaharlal Nehru has been privileged to exercise in the international world is due to the very rareness of his position and the irreplaceability of his influence. If the West short-sightedly puts that power out of action, it is the West that greatly loses, not Jawaharlal Nehru.”

Months before launching the Swatantra Party in June 1959, he wrote: “Nothing gives me greater satisfaction than the general resistance to any ‘attack’ as it is understood on Mr Jawaharlal Nehru. This is as it should be for the good of India and its future…It is God’s grace that there is a good man in India who deserves to be idolised as he is.”

Sometimes he even went against others in his party when he felt Nehru was doing something right, as happened when he backed Nehru’s stand in 1959-60 of trying to settle the border dispute with China through talks.

So was Rajaji not a trenchant critic of Nehru?

He most certainly was and delivered rebuke after scathing rebuke, without pulling any punches—through his writings in Swarajya and other publications, speeches, interviews and deliberations within the Swatantra Party.

What pitched two stalwarts of the freedom struggle and favourites of Mahatma Gandhi against each other? Historian Ramachandra Guha, a self-confessed admirer of both, writes that the two did not have much in common barring the desire to see India independent and a devotion to Gandhi, but that both had enormous regard for each other and that Nehru respected Rajaji enough to want him by his side.

Rajaji himself admitted this and countered jeers that he founded the Swatantra Party out of frustrated ambition. “I was compelled by Mr Nehru’s affectionate remonstrances to continue much beyond the time when I wished to leave Delhi. And when I did come away I did so against his wishes”.

But Rajaji could just not reconcile himself to Nehru’s socialist orientation. Whether it was Nehru’s reliance on centralized planning or his agriculture policies which tended to lean towards the Soviet model, Rajaji (and the Swatantra Party) unfailingly highlighted the harmful effects on governance and individual freedom.

Rajaji took exception to what he saw as Nehru’s attempt to force socialism down the Congress’ and India’s throat. From the time he returned from Cambridge, he wrote, Nehru “continually pressed his (socialist) bias on the Gandhian Congress but failed until he came to occupy the seat of power as sole inheritor of the prestige of liberation, when this outdated theory of governance and prosperity got its chance and was officially adopted by the Congress Party.”

The Swatantra Party was, as a right-wing alternative to the Congress, ideologically distinct from the other major right wing party, the Jan Sangh (the predecessor of the BJP). But there were attempts to brand it as the party of status quoists and traditionalists and Nehru’s Congress as a modernising force. Rajaji had an effective counter to this. Quoting noted American journalist W. H. Chamberlain, he pointed out that true conservatism “is interested in conserving property, because it is an almost indispensable support of personal liberty.”

Nor was Rajaji defensive about being dubbed a traditionalist. He was quite unapologetic about what he called “our seeking to perpetuate spiritual values and preserve what is good in our culture and tradition.” It was pointless, he argued, “in replacing systems simply because they are ‘traditional’. Survival is the proof of fitness, not of worthlessness.”

On the other hand, he charged Nehru with being out of tune with the times. “Mr Jawaharlal Nehru’s illusion about his own modernity is what befogs the whole of the Congress Party…. He and his party are still under the illusion of the modernity of their outdated doctrine of governance.”

Going a step further, he listed the distinctive features of fascism—plebeian leadership, the appeal to the mob, the contempt for legality, the disregard for the rights of property, the insistence on creating an entirely new order of things—and said that the Congress policy was very similar to these.

The Rajaji-Nehru divide on economic ideology is well-known and has been much written about, but Rajaji’s criticism of Nehru was not confined to this. He was concerned that Nehru’s style of functioning which he felt was becoming increasingly autocratic, was affecting the very fabric of Indian democracy.

Rajaji was particularly upset over the spate of amendments to the Constitution that the Nehru government was pushing through. “Unable to fit itself into the framework of the liberties enunciated in the Constitution, the Congress Party obtains through its majority in Parliament constitutional amendments cancelling those liberties, to suit the dogmas it has adopted and the regime based on them.”

The way the Congress functioned under Nehru was, for Rajaji, an antithesis of everything the organization had stood for at one time. Interestingly, Rajaji did not feel Nehru was the right man for the job of leading the Congress or the country. He described him as “a square man in a round hole” and credited Patel with keeping things going till his death. “Then came about the sad transformation of one of the most enlightened and finest national figures in Asia into a party man, intent on perpetuation of the rule of his party as the only path to glory for the country and himself.” He goes as far to say that megalomania and narcissism sum up Nehru’s weaknesses.

Though he himself kept the personal and political apart, Rajaji felt Nehru was not doing so and that his antipathy to the Swatantra Party was a reflection of his own prejudices. “Mr Jawaharlal Nehru, I fear, tries to find out our stand from the prejudices he has developed in respect of the various personalities who have publicly associated themselves with the Swatantra Party and he has not cared to study the principles accepted by the Party.”

This led to a refusal to accept mistakes. Rajaji observed how Nehru complained of character assassination when there was uproar in the early 1960s over Congress leaders using official positions to get businessmen to donate to the party coffers. This was an issue on which Rajaji was unrelenting in his criticism of Nehru, calling him out on maintaining double standards and being hypocritical.

Rajaji was unimpressed when, at one point, Nehru had said he was ashamed of these collections. He wrote: “Having insured big donations for his own party, he (Nehru) spouts abstract clichés about his objections to taking any big money from these rich people. Why did his party vigorously oppose the motion pressed in Parliament by all the other parties that companies should not be allowed to donate shareholders’ money to political parties? What about the Rs 20 lakhs given in one single gift by one Birla company?”

And then came the devastating putdown: “I have no doubt Mr Nehru feels all that he says, but he has another man within him: other than the man that feels and speaks these noble things, and it is that man that heads the party, and he will not, alas, get rid of him but sees that he abets every party abuse.”

When Nehru, in 1961, lamented the lack of integrity in the civil services, Rajaji was quick to point out that this was the result of the Congress policies and the party bosses using officials to further the prospects of the party. “How can the party chief carry conviction when he appeals with all this ugly reality which is known to every junior official?” He blames Nehru squarely responsible—“Unfortunately, or fortunately perhaps, he is the party, and the party is he.”

It was suggested by those around Nehru that Rajaji’s forceful criticism of Nehru had to do with personal pique. Though it would be incorrect to say there was no personal friction at all—Rajaji who had been part of Nehru’s cabinet did, on occasions, feel a bit sidelined—what drove his constant opposition, apart from the ideological differences, was the feeling that he was dutybound to do so. With the death of Gandhi and Sardar Patel, he believed there was no one who could give Nehru “independent and fearless advice” and that he owed it to the trust that Gandhi and Patel placed in him.

Would the history of independent India been different had Nehru listened a bit more to Rajaji than he did? The answer is Yes, but we today have the advantage of speculative hindsight.