Where Are Our Political TV Shows?

The dearth of good political shows in India is odd, given that the audience is there, and the scripts are hiding in plain sight.

In the movie Salmon Fishing in the Yemen, the slothful British bureaucracy is pushed into action by a series of quirky events. To improve its image in the Muslim world, the British Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) decides to support a Yemeni sheikh’s vision of bringing salmon fishing to his country. Faced with this seemingly preposterous task, the Commonwealth Office reluctantly consents after few threats from the PMO. The sheikh’s faith in the project inspires the chief scientist and after surmounting political opposition from locals, the project ultimately fructifies.

The film makes for great watching. The fun part is treatment of the bureaucracy. As I was watching it a few years ago, I was wondering why hasn’t any such movie or TV show made on the Indian system? There have been efforts in making overtly political movies, such as Rajneeti, with a social dimension to them. The crooked local politician has been omnipresent in our movies. But movies on how the government works or how things get done in the high offices of Lutyens’ Delhi are almost absent. Parmanu, made recently, came with a dramatised version of bureaucracy, but it wasn't even close to presenting a fair picture.

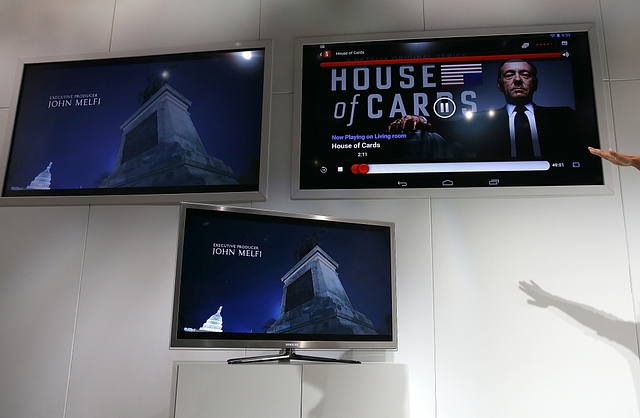

Our TV shows are no different. If you take the American soaps, from West Wing to House of Cards to Veep, they present a vivid picture of the setting of the White House. West Wing is idealistic, with a president and few youngsters being the beacons of justice and progress. House of Cards reveals the dark art of politics and policy-making, with its sinister and power-grabbing protagonists. Veep is funny, filled with the absurdities of politics and rules of governance. Each of the above offers a peek into governing structure and at least an imagined sense of what happens on a day-to-day basis in the highest office of that country. Ji Mantriji, the Hindi adaptation of Yes Minister, was probably the last such attempt made way back in 2001.

This is very surprising given that a script with colourful characters and exciting plots that could immerse the audience in a variety of emotions are right before the eyes of the directors. Visitors to any of the bhavans – Transport, Shastri, Krishi, Railway, Udyog, Nirman – would be stuck by the strangeness of the place: the usually disorganised old furniture, the crazy electric wirings, the paan stains on the walls or on the floor, the monkeys, the surfeit of idling security personnel, the various peons and helpers running around with files, the hopeless chai if you are offered one, the obsequiousness or the obstinacy of the official based on perceived aukat, the deification of the secretary or the minister, to name a few. It will be a heady mix of fear, disgust and respect.

These offices are microcosms of India, with people from Namdapha to Narayan Sarovar confined to one place, speaking their languages, eating their food, making friendships, romantic relationships and also coteries. There are layers of officials, stratified and treated on their levels, each being mean to their lower levels. (The functions they carry out would many times elicit a chuckle. There is a peon, whose main task is to lock the elevator when he receives a signal that the minister is going to arrive). There are contract employees afraid of losing their jobs and working hard, and permanent employees who spend a few hours on YouTube.

There are highly-educated policy experts, who feel that the place is incongruent to their amazing talents and how a few like them sacrifice and carry the society like Atlas. There are journalists snooping around, sweet-talking their sources to get that file for their next scoop. Then there are the Indian Administrative Service officers, the 'lord of men' who walk around with swagger and park themselves on their white-towelled thrones. Finally, there are the ministers and their personal staff that command a disproportionate amount of respect just for their proximity to the 'reigning deity'.

Anybody who has worked closely with the system would vouch for the myriad human elements and attitudes – pettiness, anger, incompetence, jealousy, humour and rare idealism – behind such a dour setting. Policies are made and nation is governed in such a seemingly chaotic atmosphere. But like a lotus in a pond, a few inspired officials work in a sea of mediocrity to guide the affairs of the country.

Any great policy would have taken a tortuous path from vision of the minister to finally seeing the light of the day. The sheer number of constituencies and interests at play from the minister’s own vision, to actions of careerist bureaucrats, to the political climate, to popular opinion, to nudges of friends of senior officials, to cognitive biases of officials, to prying media and think tanks, interests of other political constituents and their interplay would make for a fascinating drama to watch.

In a democracy, people should know how governments work. While the media watches the government like a hawk, it would help if people get a visual picture of at least the setting under which the government functions. It may even remove apprehensions and make young educated people want to join the government to create a change. There is a significant educative aspect to the proposal apart from the entertainment value.

In an interview after he made the Tamil movie, Iruvar, based on the politics of M G Ramachandran, J Jayalalithaa and M Karunanidhi, director Mani Ratnam said he was surprised that no one picked up the script that was hiding in plain sight. A TV show or a movie on Indian bureaucracy and policy-making process is one such low-hanging fruit waiting to be plucked.