The Religion They Want To Build

As Neo Paganism reclaims ground in the West, Neo Pagans want to draw on the past, yet look towards the future. Its appeal lies in the shared commons.

In Celtic Pagan mythology, Dagda is a powerful god, who controls the weather, the crops as well as time and seasons. All men worship him, for without his benevolence the crops would fail. His power is immense, exercised by the use of a magic staff called the ‘Long Anfaid’ (the mace of wrath) that can slay 10 men in a single blow. For this, he is known as the ‘Lord of the Heavens’ as well as the ‘Lord of Life and Death’. Like all Pagan gods, however, Dagda is vulnerable to human weaknesses, and one day, he finds himself irresistibly in love with Boann, the wife of the wise judge Elcmar. Afraid of the wise Elcmar, Dagda attempts a ruse to seduce Boann. He sends the judge on an errand, while he makes love to his wife, and then in order to hide Boann’s pregnancy, he holds the Sun still so that nine months pass as if one day. Accursed by her husband when he eventually learns of his wife’s infidelity, and of the god’s ruse, Boann drowns in the magical Well of Segais, giving birth to the river Boyne in modern-day Ireland.

One could be forgiven for seeing striking similarities in the amorous story of God Dagda and Boann and the forbidden affair of Indra with Ahilya. The similarities are not coincidental. At least, not for the followers of a new religious movement, known as Neo Paganism, that is fast gaining ground in the United States and Europe. Neo Pagans are attempting to recover whatever can be salvaged from the traditions of Europe’s pre-Christian past, grounded in the conviction that these traditions continue to possess values that are relevant to our own times, despite centuries, even millennia of suppression and neglect. Although centred, mostly, around pre-Christian European mythology, these modern Pagans are attempting to bring together under the rubric of Paganism all traditional beliefs outside the Judeo-Christian, monotheistic belief systems, ranging from Native American to African to Far Eastern religions to the traditions of the Australian aborigines. In doing so, the Neo Pagans also implicitly recognise the position of Indic faiths as the only Indo-European Pagan belief systems to have survived into modern times, unchanged.

At the forefront of this outreach effort between European Paganism and Indic traditions have been the followers of the Romuva religion of Lithuania — the only European Pagan religion that resisted both the spread of Christianity and the efforts of communist East Europe to have survived into the twenty-first century. In 2003, the first International Conference and Gathering of the Elders of Ancient Traditions and Cultures was held in Mumbai, under the aegis of the Romuvan Church, and the World Congress of Ethnic Religions. This was followed by an Indo-Romuva conference in New Jersey, to further strengthen the links established at the earlier conference in Mumbai.

The Delegitimising Of The Pagan In History

The word Pagan, for most readers of the English language, is not one that is associated with any positive connotations. Even though for much of human history, religion for the majority of mankind resembled what would today be identified as Paganism, but for most of our recorded history, Pagan has only meant the opposite of civilisation. Sociologist Michael Strimiska of the State University of New York, for instance, points out that The Scribner-Bantam English Dictionary (1991) provides the four following definitions of Pagan: “1. heathen; 2. idolator or worshipper of many gods; 3. one who is not a Christian, Jew or Muslim; 4. one who has no religious beliefs.” Such tropes have been further reinforced in the twentieth century by popular media including Hollywood; Steven Sepielberg’s Indiana Jones and The Temple of Doom or cult classics such as Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, come to mind, conjuring images of flesh eating cannibals and obscure satanic rituals.

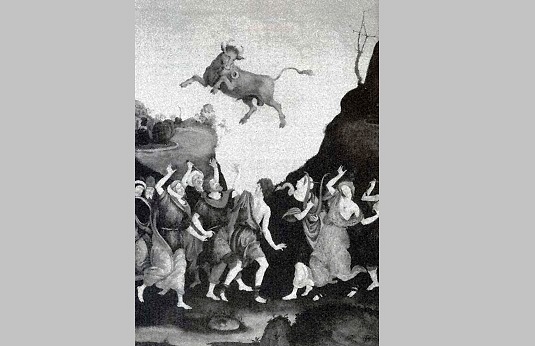

These prejudices are nothing new. They have their roots in the ancient civilisational conflicts of Europe and West Asia between the Judeo-Christian faiths on the one hand and the prevailing Pagan religions of the era. For instance, in the story of the ‘Sin of the Golden Calf’ found in the Old Testament, we learn how Moses punished the Israelites for worshipping the idol of a Golden Calf — the bull being a symbol of the Pagan beliefs held by people of the Egyptian and Babylonian civilisations for millennia.

Thus, from the beginning of the era of the ‘Text’, we see Paganism and Animism being equated with sin. The subsequent development of this delegitimising of Pagan belief systems, down to the colonial period is a familiar story. We know it from the destruction of the native cultures of the Americas, the ‘civilising’ of the savages of Africa that the colonialist proclaimed as the singular achievement of the West, and the enlightening of the idolatrous cultures of the east that Rudyard Kipling, without any irony, declared the ‘White Man’s Burden’.

Defining Neo Paganism

In the US and Europe, Neo-Paganism does not have an uninterrupted legacy to draw form. Nearly all records of Western Pagan traditions were lost by the end of the first millennium CE. Modern Paganism is thus, essentially, based on a reconstruction of whatever can be salvaged from the wreckage of history. Thus, many rituals that Neo-Pagans in the US or Europe today engage in, are products of self-conscious revival movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and not based on any certain knowledge of their ancient traditions. That being said, there are certain defining criteria on which Neo-Pagans broadly concur, and which set them apart from the more popular religions of the day. These include: recognising the importance of ritual, a belief in the re-enchantment of the world (as opposed to disenchantment ushered in by rationality based cults), polytheism, the use of idols for worship, and an affirmation of plurality of beliefs.

Additionally, Paganism believes in life affirming qualities of nature. This celebration of nature ties the various Pagan cults all over the world in one more commonality — the worship of the female deity. Since fertility is a common theme in Pagan worship, the female deity as the creator of the universe is ubiquitous in Pagan cults. By comparison, the iconoclastic-monotheistic religions of the world are marked by a near universal absence of the feminine from their sacred landscapes.

The Indo-European Roots Of Paganism

As is expected from the linguistic kinship among Indo-European languages, European Pagan cultures show striking similarities with various Indic indigenous traditions. For instance, among Lithuanian Neo Pagans, the notion of Damumas as a foundation of the world order is a central idea. According to Lithuanian ethnologist and Romuva ideologue Jonas Trinkunas, the word Damumas is linked etymologically to the Sanskrit dharma and the Pali Dhamma. J P Mallory, a prominent Indo-European scholar cites another linguistic parallel in a Lithuanian proverb — ‘Dievas dave dantis; Dievas duous duonoss’. The proverb translates as ‘God gave us teeth, God will give bread’. The Sanskrit equivalent of the proverb is Devas adadat datas, Devas dat dhanas.

Beyond linguistics, more similarities can be seen in the cosmology and religious pantheons of the two traditions. Sociologist Michael Strimiska has drawn attention to the tendency of Pagan deities to have human fallibilities. They have their passions and their pursuits, and are depicted in art in mostly human form. They fight, are frequently defeated, and are sometimes killed, they consume intoxicants, and dance, they indulge in ribald humour, and have numerous amorous encounters — all characteristics, which, in a monotheistic conceptualisation of a transcendent, all powerful god, would seem like perversions of the very idea of god. However, as Professor Strimiska points out, to Pagans, “it is these very limitations and imperfections that reflect the vicissitudes of life on earth in a far more compelling manner than the absolute perfection of a monotheistic super god”. Paganism thus represents one half of two human world views that have been at divergence since the beginning of civilisation. While the monotheistic god of organised religions exemplifies perfection and demands sanctity, the Pagan religious sensibility views its deities as a celebration of the imperfection and utter absurdity of life.

One also sees several similarities in the iconography of Pagan faiths. For instance, the motif of the Tree of Life — a cosmic tree that sustains all life in the world — appears in almost all folk traditions of the world. In Nordic mythology, for instance, the tree of life is called Yggdrasil, a holy tree that is the centre of the cosmos and connects the nine worlds of Nordic mythology.

In Hinduism, the tree of life is represented by the kalpavriksha or the kalpataru, believed to be represented by different species in different parts of the subcontinent — from the pipal and the banyan in the tropical south and east to the khejri or jand in the arid northwest. Similarly, motifs such as the swastika have been known for long to be common to several pre-Christian civilisations. The appropriation of the swastika by the racist and totalitarian ideology of the Nazis, and the horrors of the Second World War, however, still cast a dark shadow over attempts to find a common ground among Indo-European Pagan cultures. Despite this, Neo-Pagans such as the Lithuanian Romuva are taking small steps to reconstruct their heritage, while staying clear of the racist, nationalist, and political rhetoric that comes along with attempts to reclaim the past. The Romuva flag, unsurprisingly, features a modified swastika. In a region still wrecked by memories of the Holocaust and where resurgence of Neo-Nazism remains a threat to peace, the swastika, in any form, still arouses a fair share of suspicion.

The ‘othering’ of Pagans, and the labelling of their ways of worship as being incorrect has been a historical wrong that has taken a long time in being popularly acknowledged. From being the mode of worship of all humanity at the beginning of civilisation, to now being reduced to small pockets of resistance, Paganism has come a long way. The reclaiming of Paganism and witchcraft by Neo Pagans from their centuries old association with sin and evil also needs to be seen as a reaction against the overbearing rationality of the age of technology. In a world where everything runs on code, steel and concrete, the appeal of Neo Paganism lies in discovering a little magic in the shared commons — the wind, the ocean, the rain, and the Earth.

At the same time, it is important to avoid falling into a nostalgic stupor for an idyllic past. Not all things Pagan are necessarily glorious — many Pagan rituals, particularly human and animal sacrifices, have a dark and disturbing past. Neo Pagans of all persuasions though are clear that the religion they want to build is one that draws on the past but also looks towards the future, like the Nordic Tree of Life, the Yggdrasil, that has roots in the underworld, while its branches extend far into the heavens.