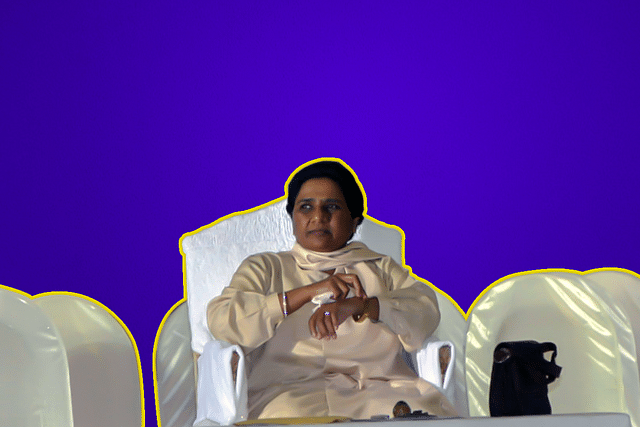

The Rajasthan Insult: Are BSP And Mayawati Sliding Into Irrelevance?

Electoral setbacks and absence of a second line of leadership has raised questions over BSP’s future.

What would the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) of Mayawati look like in 2022, when elections to the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Vidhan Sabha are due next?

Less than a decade ago, this question would have been laughed at and dismissed. Rightly so.

However, a news story that broke today brought to attention the threat of irrelevance over the BSP and, more so, over Mayawati.

All the six lawmakers of the BSP in the Rajasthan Vidhan Sabha joined the Congress today. In an assembly of 200, the Congress has 100 members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs). The BSP contingent of six was supporting the Congress from outside. After the switchover, reports say that a cabinet reshuffle is on the cards in Rajasthan.

This news was followed by a series of angry tweets by BSP chief Mayawati on Twitter. Terming the Congress as unreliable, Mayawati said that the Congress had proved itself to be opposed to the reservation of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes.

She even invoked the history of early independent India to make her point that Congress had even been against the ideas and works of Dr B R Ambedkar.

Even if the BSP chief had not reacted this way on social media, and even if the six MLAs were still in her party, the increasing irrelevance of Mayawati and BSP could not be missed by a serious observer.

The most convincing proof of that is the numbers that the BSP has returned since 2014 in UP, its home turf under Mayawati.

In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the BSP garnered 19.8 per cent of the vote share in UP. This was down from 27.4 per cent in 2009. However, it was unable to win a single seat out of a total of 80.

In 2019, it got 19.26 per cent of the votes and won in 10 seats. However, this was after an alliance with its arch rival, the Samajwadi Party.

Likewise, in the UP assembly elections of 2017, the BSP won a mere 19 seats of a total of 403. Their vote share in this election was 22.4 per cent.

This was around 4 percentage points lesser than the vote share in 2012, which stood at 25.9 per cent. This itself was a drop from their historic high of 30.4 per cent in 2007, the year when Mayawati became the chief minister for a full term.

And it’s not just the numbers which bear out BSP’s slide. Anecdotal evidence does too.

Less than ten years ago, in the mainstream media, you would read about Dalits being the core vote bank of the BSP in UP. In recent years, ‘Dalit’ has been increasingly replaced by ‘Jatav’, a sub-caste within the Dalits, but the largest of the lot.

What this signals is what many observers bear out. That all Dalits do not vote for the BSP, and an increasing number of non-Jatav Dalits in UP have shifted to the BJP since 2014.

The second reason why irrelevance appears to be staring at the BSP is the complete absence of a second-rung leadership.

Any leader who has a credible ground support and support outside of his constituency, either finds himself out of the party, or leaves the BSP and creates his own outfit, or joins another party.

Many of these leaders had been with the BSP since the days of Kanshi Ram but found themselves marginalised under Mayawati.

Interestingly, even in the Madhya Pradesh (MP) assembly, the BSP is supporting the Congress government which is running on a tenuous majority. Till the time of writing, there was no word from the BSP on whether it would continue to do so in MP.

In 2004, Sonia Gandhi, the then Congress president, had walked over to Mayawati’s house for a meeting some weeks before the general election. Today, till the time of publication, she is yet to react to Mayawati’s outburst.

The one reaction that did come came from Rajasthan’s chief minister, Ashok Gehlot:

What Mayawati has said, I feel that such a reaction is quite natural… but she must understand that the people sitting in the government didn’t manage it. We didn’t lure them and it is our state’s quality that we never indulge in horse-trading...The MLAs were aware of the conditions in Rajasthan, they knew the sentiments of the people and joined the government to help accelerate the pace of growth. The government should remain stable and this was perhaps in their mind… there was no pressure from our end.

Maywati is too seasoned a politician to not know what Ashok Gehlot’s doing here.

Less than a decade ago, the Congress would have sent emissaries to placate the BSP chief. Today, Mayawati must convince herself.