This Janamashtami, Here Are Five Krishna Devotees With Their Soulful Poems And Powerful Stories

On the beautiful festival of Krishna Ashtami, here are some Krishna devotees and their beautiful, heart-warming poems, which are as sweet as their stories are powerful.

Raskhan

Raskhan, a devotee of Lord Krishna was born in a prominent Muslim family in 17th century. He later devoted his life to Krishna Bhakti and went to Vrindavan, where he stayed till his death.

One time, Raskhan wasn’t allowed into the Srinath temple in Vrindavana on account of him being born in Muslim faith. Raskhan, not being able to meet his beloved Krishna, felt heartbroken. He couldn’t eat, drink or sleep. It is said that then Krishna himself appeared and apologised for the temple priest’s behaviour.

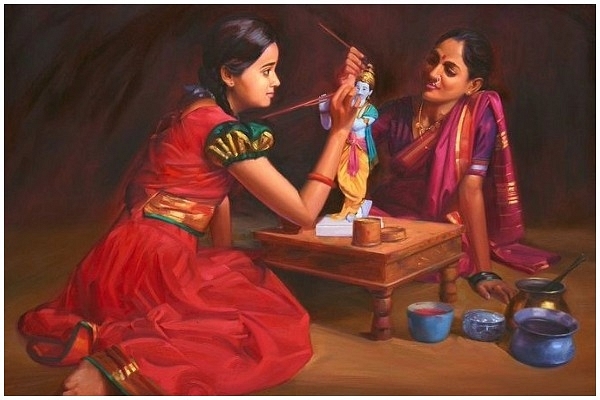

Here’s how Raskhan describes the leela of Baal Gopal (Baby Krishna).

धूरि भरे अति शोभित श्याम जू, तैसी बनी सिर सुन्दर चोटी।

खेलत खात फिरैं अँगना, पग पैंजनिया कटि पीरी कछौटी।।

वा छवि को रसखान विलोकत, वारत काम कलानिधि कोटी।

काग के भाग कहा कहिए हरि हाथ सों ले गयो माखन रोटी।।

Adorned with a beautiful choti (a hairstyle), baby Krishna plays in the courtyard. He is full of dust and his painjaniya (an ankle-ornament with bells) makes beautiful noise as he runs around. Raskhan is mesmerised by the sight. He envies the lucky crow, who is able to snatch Maakhan-Roti (bread and butter) from the hands of Hari himself.

Nabai Moyra

The 19th century poet from West Bengal describes the unity of Kali and Krishna beautifully. The devotee of Shyama (Kali) requests the fierce Goddess to strike the pose of ‘sweet Krishna’ for his sake.

Strike the bent pose of sweet Krishna

when he dances with the cowherd-girls;

come stand in the shrine

of the heart's temple.

Come show yourself

as the charming crooked one

with Radha at your side.

Take off your skirt of human arms

and put on the yellow dhoti

of the cowherd god.

Put the peacock feather on your head,

and crook one foot over the other.

Abandon your garland of human heads

and put on the garland of forest flowers instead.

Be the Dark Charmer for once,

and not the Black Destroyer.

O woman with heart of stone,

the lotus of my heart blossoms

when it sees the black moon!

Just once, drop the sword

and pick up the bamboo flute!

Fulfill the yearning of the faithful!

The beauty of Bhakti is that the devotee has the bhag of the Krishna, and Krishna shares the bhag of the devotee. Without the encumbrances of complex literature and rituals, prabhu and bhakt become one.

In a creation rightly called Moha Mudgara (the remover of delusions), Sankaracharya tells an old man on the verge of death trying to learn Sanskrit on the banks of Kashi:

भज गोविन्दं भज गोविन्दं गोविन्दं भज मूढमते।

सम्प्राप्ते सन्निहिते काले नहि नहि रक्षति डुकृङ्करणे।।

Worship Govinda, worship Govinda, worship Govinda, Oh fool! Rules of grammar will not save you at the time of your death.

That the proponent of Advaita Vedanta says so shows how the simple path of Bhakti remains the refuge in the tough times of Kaliyuga. In fact, in Kaliyuga, Bhakti becomes the armour of those exploited and downtrodden, suffering the yoke of Papacharanam that eclipses Dharma in Kaliyuga.

Chokhamela

Chokhamela was a 14th century saint who was born in Maharashtra in an ‘untouchable’ caste. A devotee of Vitthala, Chokhamela dedicated his life to the Lord and wrote several Abhangs which remain popular to this day.

For Chokhamela, his beloved Krishna comes to the rescue against social evil of untouchability. A well-known story goes like this.

One day Chokha stood at the door of the temple from morning till late in the evening, not allowed by the priests inside. As the night came, the priests locked up the doors of the temple and went away. Chokha was still standing, tired and alone, when Vitthoba himself came out, exclaimed in distress to see Chokha patiently waiting.

The Lord embraced Chokha, led him by the hand to the garbhgriha, where he lovingly held him to his breast. The night was spent in the union of the bhakt with the god, after which Vitthoba playfully removed his Tulsi garland and put it around Chokha’s neck.

When the day dawned, the Lord himself led Chokha out of the temple and then disappeared. Chokha, in a state of bliss having experienced the divine love, lay down on the sands of the river in a trance.

On the other hand, at the temple, the priests discovered that Vitthoba’s gold necklace was missing. Remembering that Chokha had been at the temple doors last night, they suspected his hand, and went into rage over the fact that the temple and the deity were polluted. They set out to look for him.

Chokha, still dazed and uncomprehending, but with a gold necklace around the neck was found on the sand. He was punished; tied to the bullocks and about to be dragged to death.

The devotee then exhorts Vishnu that now that their ‘secret love’ was no more a secret, the Lord himself will have to come and own it. The heart-wrenching poem goes like this:

They thrash me, Vithu,

now don’t walk so slow.

The pandits whip,

some crime,

don’t know what:

How did Vithoba’s necklace come round your throat,

they curse and strike

and say I polluted you.

Do not send the cur at your door away,

giver of everything.

You, Chakrapani, yours is the deed.

With folded hands

Chokha begs

I revealed our secret,

don’t turn away.

On Chokha’s request, Vitthoba himself intervenes. The bullocks to which Chokha is tied, refuse to move, despite whips. Then Vithobha reveals himself to the company, holding the bullocks by the horns.

True to the concept of Bhakti, not only Chokha shares the divine love of Vithobha, but Vithobha also shares the socially imposed ‘pollutedness’ of Chokha. If Bhakt Chokha, who is one with Lord is ‘impure’ and inauspicious, then what is not?

Chokha says:

Vedas and the Shastras polluted;

Puranas inauspicious impure;

the body, the soul contaminated;

the manifest Being is the same. Brahma polluted, Vishnu too;

Shankar is impure, inauspicious.

Birth impure, dying is impure: says Chokha

pollution stretches without beginning and end.

Andal

Andal or Godadevi is not unknown to any Krishna-bhakta. One of the twelve Alwars, Andal is credited with the great Tamil works, Thiruppavai and Nachiar Tirumozhi.

In the following verse, Andal describes her longing for Krishna. The verse is radical in its expression of unification of jeevatma and Paramatma. The device of worldly love and pleasure is used to express this union. Physical union becomes a metaphor for the union with the ultimate.

Only if he will come

My life will be spared

To stay for me for one night

If he will enter me,

So as to leave

the imprint of his saffron paste

upon my breasts

Mixing, churning, maddening me inside,

Gathering my swollen ripeness

Spilling nectar,

As my body and blood

Bursts into flower.

I pine and languish

but he cares not whether I live or die

If I see that thief of Govardhana

that looting robber, that plunderer

I shall pluck out by their roots

these breasts that have known no gain

I shall take them

and fling them at his chest

putting out the hell-fire

which burns within me

While the above poem, in its brazenness, shakes the conventional notions associated with sainthood, the elaborate and beautiful description of the the Lord with his consort is commonplace in Hinduism.

कमलाकुच चूचुक कुङ्कमतो

नियतारुणि तातुल नीलतनो |

कमलायत लोचन लोकपते

विजयीभव वेङ्कट शैलपते ||

Oh Lord whose matchless dark hued body is always rendered red with the vermilion marks from the breasts of Lakshmi ! Victory be always to Thee!

There is no guilt or shame associated with sex in Hindu culture. However, in her desire to be with Krishna, Andal's boldness is startling.

The desire for union with opposite sex and the desire of union with the Ultimate both involve going beyond the narrow physical boundaries of self. Love, therefore, becomes a perfect symbol for spiritual yearning. Both are are deeply personal, and constitute a lonely, mysterious journey away from worldliness.

Perhaps, the best metaphor that can be used for the true spiritual satiation is sex, both are deeply individualistic, mysterious yet socially significant activities.

Camile Paglia says, “The background from which and against which our ideas of God were formed, nature, including sex, since “sex is a subset to nature”, remains the supreme moral problem”. The western culture, perhaps for this reason, tried to suppress both.

On the other hand, symbolism of sex and nature abound in Hindu religious literature. Both become the instruments to the divine when one is on the path of Moksha.

In Indian tradition, God is not the juxtaposition to Satan. God is not one side of the the good versus evil, order versus chaos, holy versus sinful dichotomy.

Krishna is beyond the worldly distinctions and differences. All the great contradictions of the world get resolved and become one as they reach Krishna. Krishna is Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram. The Ultimate Truth is the ultimate unifier, immensely beneficial and immensely beautiful.

For sustenance of the world, Dharma is paramount, the differentiation between good and bad, helpful and harmful, right and wrong is necessary, control over bodily impulses is necessary. But for Andal who has long forsaken this world, aiming for Moksha, every impulse only takes her closer and closer to her Krishna.

Integrating contradictions is at the core of the Hindu philosophy. One example is the contradiction between Dharma (which requires discrimination and differentiation between good and bad) and Moksha (which requires an inclusive consciousness towards the whole universe).

Conventional notions of good and bad, desirable and undesirable keep changing with time. They learn, interact and mix with each other. They shed some facets and gain new ones. One’s Dharma is never static. The correct course of action always depends on the situation. After fulfilling important duties of life, the Dharma of a man becomes to strive for Moksha.

Regardless of which path a person takes, he may still reach Hari, given that, the path is pursued with selflessness, such that aham becomes more and more inclusive towards the whole universe.

On the other hand, any path, good or bad, if not pursued with selflessness, a man’s aham (ego) can expand so much as to destroy the whole universe for own pleasure.

In her expression for the longing for Krishna, Andal is as radical in shunning the socially-desirable path as are the aghoris in Varanasi. Yet, she remains popular among young girls who sing her songs joyfully during the winter festival season of Margazhi.

त्वयि मयि चान्यत्रैको विष्णु-

र्व्यर्थं कुप्यसि मय्यसहिष्णुः ।

भव समचित्तः सर्वत्र त्वं

वाञ्छस्यचिराद्यदि विष्णुत्वम् ॥

“In me, in you and in everything, none but the same Vishnu dwells. Your anger and impatience is meaningless. If you wish to attain the status of Vishnu, have equanimity, always.”