Central Vista: Demand For More Consultations Is Code For Giving Vested Interests Right To Veto

Consultation does not have to be widespread to be effective.

Carrying democratic consultation to its logical extreme means deadlock and stagnation.

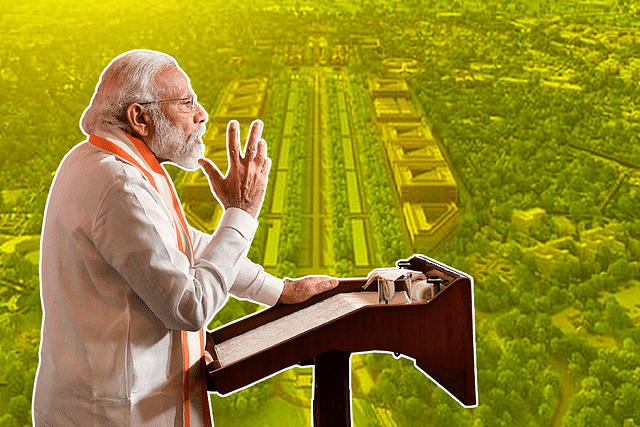

One of the big points of disagreement among those opposed to the Central Vista redevelopment project in Lutyens Delhi, which includes a new and more spacious parliament building, is that not enough consultation was done with the public on the issue.

This point was argued by petitioners during the hearings in the Supreme Court, which cleared the project in a 2-1 judgement on Tuesday. It was also a major reason why the dissenting judge, Sanjeev Khanna, disagreed with the majority judgement delivered by Justices A M Khanwilkar and Dinesh Maheshwari.

Justice Khanna’s dissent had no problems with the project bid notice or the award of the consultancy contract or the Delhi Urban Arts Commission’s nod for the project, but about the lack of public consultation which “inspires and connects common people to the citadels of our democracy”.

While he wanted the project’s land use change quashed and wanted to refer the matter back to the Heritage Conservation Committee, his essential point was that the “public should be provided not only with information about the draft scheme but also an outline of realistic alternatives and indication of the main reasons for the authority’s adoption of the draft scheme.”

In theory, more consultations and more public discussions are good for a democracy, but in practice consultations make sense only when the people consulted are qualified to understand the real issues.

The Rs 20,000 crore Central Vista project, which includes a new central secretariat, cannot meaningfully be put to a popular vote even based on much higher disclosures about alternatives and options.

This is like SEBI (Securities and Exchange Board of India) demanding widespread public discussions with all possible investors before any company launches an IPO (initial public offer). Even though there are prospectuses running into several hundred pages, few people outside the merchant banking community or mutual funds know how to read these disclosures and make sense of them.

In short, meaningful consultations mean discussions with the knowledgeable elite.

But there is a problem here too. Given India’s extreme diversity, even the expert elite cannot be said to be driven by public interest alone. They are subject to “the agency problem”, where their own interests may differ from that of the people or civil society they claim to represent.

At times, they may covertly represent some unseen private interests that have economic stakes in making changes to policies or plans.

For example, many of Mumbai’s environmental do-gooders oppose higher FSIs (floor space indices) for new construction, which means less vertical growth in land-scarce Mumbai. But this “stand in favour of the environment” also benefits builders who currently hold excess inventories of unsold flats in central Mumbai. It is not unreasonable to suspect that environmental concerns sometimes converge with the interests of the realty sector.

The other problem in India’s case is the excess of diversity, which ensures that no law – howsoever beneficial to a large majority – will pass muster with some vested interests. Case in point: the farm laws which have been opposed by richer farmers in Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh. Wider consultations here would have meant scuttling the reforms altogether. One section would have effectively wielded a veto that would have benefited larger sections of farmers.

In many past decisions, widespread consultations with all kinds of political and economic stakeholders have only made decision-making worse. For example, the goods and services tax (GST). Every state was taken into confidence, and barring Tamil Nadu, all states were brought on board at a high compensation cost and with a bad duty structure. An ideal GST structure eludes us even today thanks to the need for a wide consensus.

Similarly, we have a bad land acquisition law, and a bad food security law and a terrible Right to Education Act. Only bad laws seem to find consensus, and these happen even without consultations with stakeholders. If today, any government were to suggest giving everyone and the dog at the lamp-post a payment of Rs 5,000 a month, no one will demand consultations on the fiscal impact of this freebie. Rather, the critics will say that Rs 5,000 is too little, and that larger follies must be attempted.

Or consider the laws to end article 370 and the Citizenship Amendment Act. Was any consensus possible on these laws? Even the Congress agrees that it can go, but they object to the “process” followed. Or, would West Bengal and Assam agree on the same draft of the CAA? Will a future National Register of Citizens – now unlikely – happen through a consensus ever?

The short point is this: consultation does not have to be widespread to be effective. Carrying democratic consultation to its logical extreme means deadlock and stagnation. Or worse, a badly drafted compromise. When so-called “liberals” complain about the lack of consultation, they essentially are talking in code: what they want is the right to veto, or consensus at a price – their price.

If everyone with any kind of view had been consulted on the Central Vista, it would never happen in the lifetime of any parliament. Often, democracy works on the basis of a coalition of the willing.