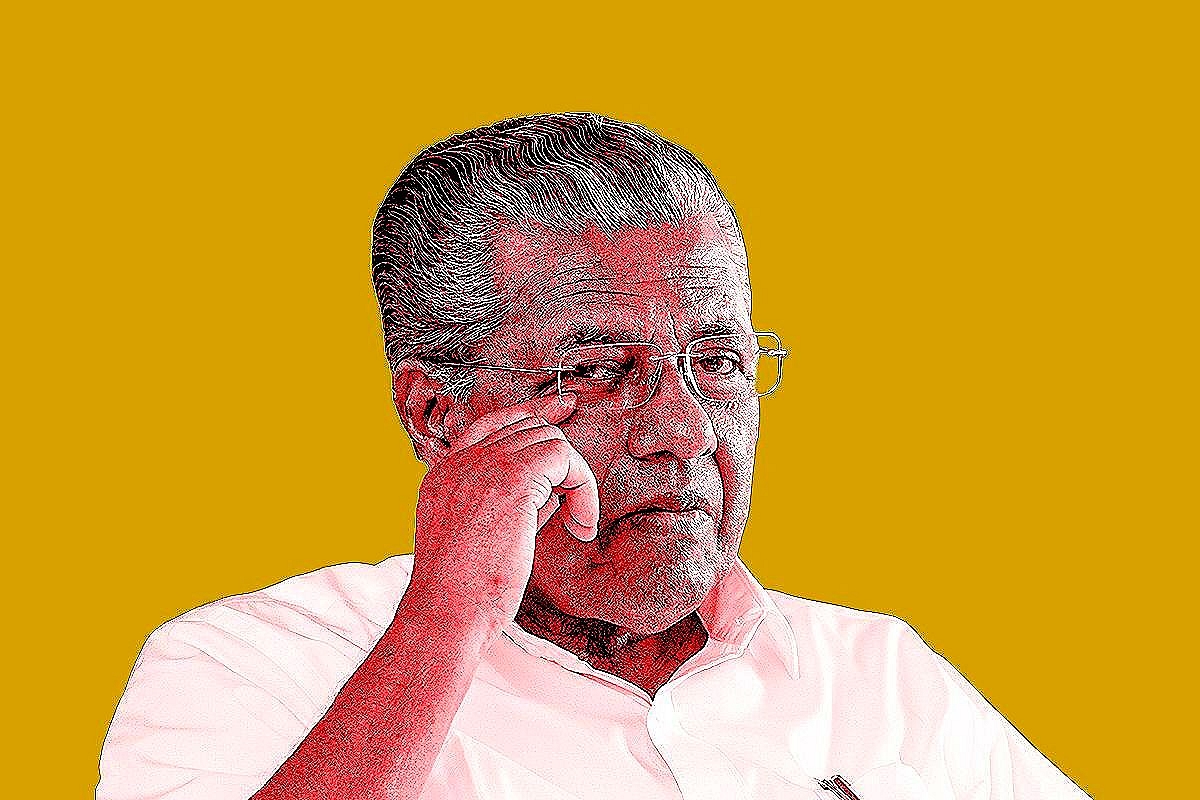

Covid-19 Fight: Pinarayi Vijayan Has Become A Prisoner Of His Own Media Image; Communist ‘Kerala Model’ Is Falling Apart

The ‘Kerala model’ remained unquestioned by both a curiously-cowed opposition and an overawed press.

But now it seems to be falling apart.

The so-called ‘Kerala model’, aggressively promoted by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan appears to be coming apart at the seams – both fiscally and in managing the Wuhan coronavirus pandemic.

Yet, two weeks ago, when Swarajya first started asking hard questions of Vijayan’s communist government, it was a lone voice disputing both the Marxists’ public reporting of the pandemic, and its management.

These queries seemed in bad taste, since, as per Vijayan’s daily evening press conferences (gushingly dubbed ‘sunset meetings’ by a formidable public relations brigade), the count of positive cases in the state was in steady decline.

They were down to the low single digits, quarantine was in full effect, and every last Nizamuddin Markaz returnee had apparently been accounted for by the end of March.

On the administrative front, Vijayan was busy declaring fresh welfare schemes, dutifully zoning districts in colour schemes, planning an exit strategy which would be the envy of the known world, announcing grand economic recovery packages, and preparing for the return of lakhs of Malayalees from the Gulf.

In the backdrop, while numerous foreign publications were writing touching pieces about how the communists’ ‘Kerala model’ was the best thing since sliced bread, the statistical veracity of these claims remained studiously unquestioned by both a curiously-cowed opposition, and an overawed press.

But not a day after the first probing queries were published, and an article appeared, hastily confirming that yes, well, while all the Tablighi Jamaat returnees were accounted for, there might or might not be a few, who might or might not be accounted for. This is what happens when journalism becomes indistinguishable from meteorology.

The same day, there was a spurt in cases, and the count started climbing up again. Only 51 cases were reported between 10 and 20 April; as many more were reported over the next three days. While this trend shift confirmed that the doubts raised were not misplaced, it ended up raising more doubts, because now, the scanty details supplied made no sense.

If Vijayan was to be believed, individuals were manifesting symptoms three to four weeks after their last probable points of infection – a medical incongruity.

Even more incredulously, a chunk of the fresh cases were located in two districts, Kottayam and Idukki, which had just been declared virus-free, and hence graded green; meaning, that they were set to exit the lockdown first.

Both became containment zones instead. As a result, Kerala was forced to witness the utter absurdity of two districts going from green to red in a matter of days. The ongoing controversy, over the origins of fresh cases in these districts, is another story entirely.

To make matters worse, Vijayan tied himself up in knots at sunset on 28 April, by saying that only four cases had been reported in Kerala that day – all from the North Malabar hotspots of Kannur and Kasaragod. That’s when the balloon went up. The hitherto-cowed local press howled in protest, since reports had already emerged from Idukki district of three new cases. Why were those not on the tally, they asked? Vijayan’s response was baffling: it wasn’t three cases from Idukki alone, he said, but 25 from the state, and all the samples had been sent back for re-testing.

Further, to add to everyone’s consternation, he blithely chose not to divulge any patient or contact tracing details. He avoided further questions, on what was an unnerving first in India – of positive cases being inexplicably and unfathomably pushed back into the system, instead of being reported.

For aficionados of Orwellian doublespeak and Solzhenitsyn’s account of Soviet labour camps, it was ‘1984’ and the Gulag redux – a return to a time when ‘the masses’ only got to hear what was good for them, and when questions invited severe retribution.

Was this the ‘Kerala model’ the rest of the world was supposed to duplicate?

Perhaps, while Vijayan might have the political nous to nip a presser in the bud of unruly bloom, a cautious forecast predicts that not all the PR heft in the world is going to save him from this one.

Still, leaving that aside, there remains the bigger issue of public administration; the very real nuts-and-bolts duty of running a government during a crisis. That Marxist model was punctured gloriously when the state’s Finance Minister, Dr Thomas Isaac, admitted that Kerala was broke. The consequence of such an insouciant confession is that there is no money to pay government salaries and pensions next month.

Is this where the Marxists have brought Kerala to, after four long years?

The answers will no doubt be played out more fully, during the build-up to the assembly elections due next year, but in the interim, it also brings the Marxists into conflict with the trade unions.

More pertinently, it brings into question the financial viability of Vijayan’s proposed economic packages, and lavish plans to bring back hundreds of thousands of Keralites stuck in the Middle East.

Is this why the Leftist PR brigade has started building a doleful narrative of late, of the Centre needing to help out? If yes, then it does a state’s credibility no good. Especially if a Chief Minister generously announces a package, only to follow that up with a letter to the Centre, asking if funds are available (which letter, of course, gets promptly leaked to the press).

Indeed, if this keeps up, the communists won’t be able to extort even ‘gaze-money’ (noku-kuli, a kind of hafta).

What we see here then, is a man trapped in the public persona of his party’s stylists, without the substance to back that up.

He was repeatedly advised, quietly, politely, not to foist an alleged ‘Kerala model’, of suspect credence, upon the public. All he had to do was his job. But it appears that the temptation to notch up a few political points (in the midst of a raging epidemic, no less), and burnish a rusty Marxist image, was too great to abjure.

A pity; Vijayan should have known better, for, in Kerala, they disparagingly call that “selling locks during Onam”.

Nevertheless, while Vijayan is free to become a prisoner of his own media image, he has no right to put Kerala at risk.

Similarly, if he can’t pay for the grandiose schemes he announces, let him either not make those announcements, or let him get the money from the Centre first.

Either way, it is expected that Vijayan comes clean soon on patient details, sample testing results, and an unambiguous picture of the current situation in Kerala.

This is necessary, because millions of people have to return to work very soon, and, because it would be wrong to expect that return to normalcy, while grave questions of public health and finance remain unanswered.