Despite Being CAA Beneficiary, Church Sees Gains From A Limited Tactical Alliance With Mosque

While Muslim organisations have been vociferous in their anti-CAA protests, the church has kept quiet.

Now, that silence has ended, for the church sees short-term benefits in a tactical alliance between two of India’s minorities.

The church in India appears to have taken a strategic decision to oppose the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019 (CAA), which fast-tracks citizenship to minorities in three Muslim countries in the neighbourhood. And this even though persecuted Christian minorities are directly benefited under the CAA.

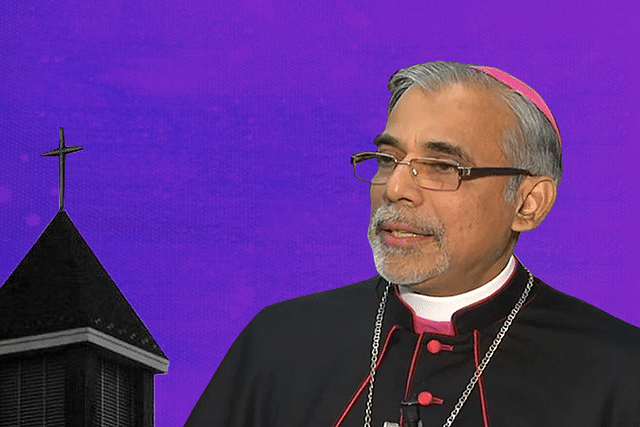

Last month, Joseph Powathil, Archbishop of the Syro-Malabar Church, opposed the CAA on the ground that it was an effort by the government to drive a wedge between Christians and Muslims. Last week, the Archbishop of Goa, Filipe Neri Ferrao, called on the government to “immediately and unconditionally revoke the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA)” and stop stamping on the “right to dissent”. He said the laws were “divisive and discriminatory” and will damage the country’s multi-cultural democracy. Apparently, he thinks that the church’s own agenda of pitting upper caste Hindus against Dalits, and the “one true god” against worshippers of “false gods” is somehow not divisive.

This marks an about-turn for the church, for in December 2019, soon after the CAA was passed by Parliament, George Kurian, Vice-Chairman of the National Minorities Commission, welcomed the CAA. He pointed out that “those who are vociferously advocating minority rights in India are silent on the persecution of minorities in Pakistan.” Kurian said the commission had received several messages from many Christian denominations welcoming the act. “They tell me”, he is quoted as saying, “justice has finally been done to Christians who are victims of draconian blasphemy laws, religious conversions and abductions.”

The church in India has clearly had a rethink, if one were to go by the anti-CAA statements of the two archbishops. They have probably calculated that despite their interest in protecting the Christian minorities in Pakistan and Bangladesh, the real market for conversion is in India, and this requires the church to play the victim card in India and oppose most things that the Narendra Modi government does.

The church has taken this stance even though it knows that in Kerala Christians are also being targeted by Islamist groups. The same Syro-Malabar Church earlier alleged that Christian girls were being targeted and killed by jihadists through ‘love jihad’.

The church probably believes that its long-term conversion agenda will be hampered if it is seen as supportive of CAA, since this will then open another front with the Islamists when it would prefer to target the Modi government over its alleged Hindutva agenda. The church’s conversion agenda works best in a climate where it can claim victimisation by Hindutva forces when raising funds abroad. This needs it to forge a tactical alliance with Islamists in India, even though its long-term rival in the marketplace for conversions is Islam.

The archbishops can clearly be accused of hypocrisy, for in India it is only minorities who get special laws – from separate minority commissions to the constitutionally-mandated right to administer their own educational and religious institutions. The fact that such religion-based discrimination exists against the majority community is being deliberately ignored by the church in pursuit of its narrower conversion agenda, which requires it to paint Hindus (or rather Hindutva) as some kind of Frankenstein monster preying on the poor and the weak – and the minorities.

It is clear that church and mosque have closed ranks in order to pursue their own conversion agendas. Their interests do not coincide on the CAA, but their longer-term agendas do find a temporary point of tactical convergence.

Until recently, while Muslim organisations have been vociferous in their anti-CAA protests, the church has kept quiet. Now, that silence has ended, for the church sees short-term benefits in a tactical alliance between two of India’s minorities.