Explained: Why The Assamese Are Agitating Against CAB

The Assamese look at the issue from the linguistic, and not any religious angle. For them, Bengalis are one large linguistic community who are growing in numbers and could, one day, become numerically stronger than them. And no community would like to be reduced to a minority in its own state.

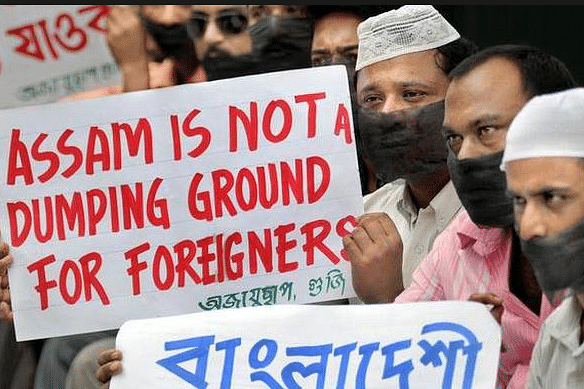

Assam has been up in flames over the past few days, and there are no signs of the fire ebbing anytime soon. And there is a strong and genuine reason for their agitation.

It is the present and real fear over being swamped by Bengali-speaking people, of being reduced to a minority in their own state, and of losing their linguistic culture and identity that is driving the protests that are scorching and ravaging the state.

The Assamese have, since the 1940s, lived under the shadow of this fear. That’s because the Bengalis of neighbouring East Bengal (now Bangladesh) are far stronger numerically (as a community).

The Bengalis from East Bengal have been migrating to and settling down in what was once a sparsely-populated Assam since the British era.

It was the British who first started the practice of organised re-settlement of Bengalis in Assam, and the rest of the North East as well.

The British brought in Bengalis who had taken advantage of western education in schools and colleges established by them (the British), to work as clerical staff in tea gardens and as lower and mid-level bureaucrats in government.

Bengali Hindu migrants from East Bengal became school-teachers, petty bureaucrats and, over time, came to dominate the professions. The British soon realised that the vast tracts of fertile land in Assam need to be cultivated, and so brought in lakhs of Bengali Muslims to work as peasants.

The migration of Bengali Muslims peaked during the premiership of Muhammed Saadulah for three terms from 1937 to 1946. He launched a determined bid to make Assam a Muslim-majority province and it was during his time that the population of Bengali Muslims in Assam rose exponentially.

The migration of Bengalis, both Hindus and Muslims, continued unabated after 1947. While the Muslims migrated for economic reasons -- to work as peasants and unskilled labourers -- the Hindus migrated largely due to religious persecution in East Pakistan (and then Bangladesh).

Generations of Assamese have seen Bengalis (Hindus and Muslims) settling in and populating their lands. This, understandably, fuelled resentment. This deep-seated resentment was further accentuated by the refusal of Bengalis to imbibe the culture and traditions of Assam and blend in with the Assamese.

Today, the Assamese are becoming a minority in Assam: the Assamese-speaking people are less than 45 per cent of the state’s population.

Though the Bengalis form a lower 30 per cent of the state’s population, they are still the second-largest linguistic community in the state and are, thus, viewed as the biggest existential threat by the Assamese.

Migrants from Nepal and other states like Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar make for the rest of the state’s population.

The Assamese look at the issue from the linguistic, and not any religious angle. For them, Bengalis are one large linguistic community who are growing in numbers and could, one day, become numerically stronger than them.

The Assamese view the CAB (Citizenship Amendment Bill) as a legislation that will grant citizenship to Bengali-speaking migrants from Bangladesh. And that is something they do not want.

This desire to preserve the already-skewed demography of the state by the Assamese is understandable, and needs to be respected.

No community would like to be reduced to a minority in its own state. The Assamese may be the single-largest community in Assam, but their numbers are well below the simple majority mark.

The deep-seated fear of their percentage (of the state’s population) falling further, stoked by the continued migration of Bengalis from Bangladesh and resentment over the insularity of the Bengalis, has led to the Assamese vehemently protesting the CAB.