How Structural Reformers Change Economies

Structural reforms—the kind of which Prime Minister Modi is attempting— are necessarily painful in the beginning.

The PM’s three resets

Over the past six months, I have highlighted in my columns that the PM is trying to reform the Indian economy along three specific dimensions:

- Altering the subsidy regime – by cutting the quantum of subsidies and by moving subsidies to the Direct Benefit Transfer platform – and thus adversely impacting rural consumption.

- Signaling to crony capitalists that it is not “business as usual” for this subset of Indian businessmen who use lobbying to routinely bend policy in their favour.

- Attacking black money publicly through the Foreign Income and Undisclosed Assets Bill, 2015 (also called the “Black Money Bill”) which after a 90-day amnesty window expires, punishes Indians who have undisclosed wealth abroad with a ten year jail sentence.

Why structural reforms entail short-term pain?

Structural reform usually entails short-term pain as economic agents (workers, bankers and business people) struggle to cope with the altered rules of economic adjustment. As theOECD’s ( economists put it in 2012, “…it takes time for reforms to pay off, typically at least a couple of years. This is partly because their benefits materialise through firm entry and increased hiring, both of which are gradual processes, while any reform-driven layoffs are immediate.”

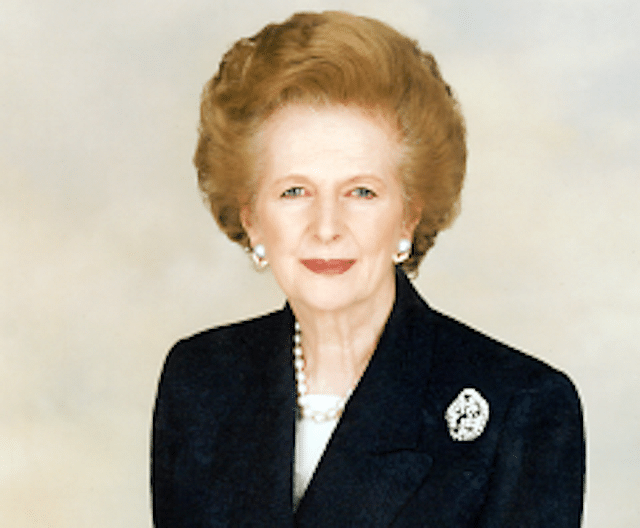

Britain under Margaret Thatcher, India after the 1991 reforms and Indonesia after the East Asian crisis give us a clear picture of what is likely to happen to India as Prime Minister Modi’s economic resets hit home:

- In the UK, Thatcher began the economic reform process in 1980. GDP growth initially fell to -2% due to these reforms but then recovered from 1982 onwards. In particular, investment initially suffered under Thatcher as she kept monetary and fiscal policies tight. As inflation expectations were brought down, private investment gathered pace.

- In India, economic reforms began in 1991 in the wake of a Balance of Payments crisis. GDP growth fell to 1% in FY92 but then recovered from FY93 onwards as with the end of the “license-permit-quota raj” investment rebounded sharply.

- In Indonesia, reforms began in 1997 in the aftermath of the East Asian crisis, economic growth fell to -13% in 1998 and investment collapsed. Then on the back of large currency devaluation and more freedom for smaller businesses (as opposed to the large firms run by President Suharto and his cronies), investment gradually recovered from 2000 onwards.

These examples have a common feature: economic growth and investment nose dive during the initial phase of reform, as the rules governing the economy, are radically altered by reform and economic agents struggle to adjust to this change. Gradually, the reforms put the economy on a sustainable growth path as against the growth fuelled by excessive government spending (as was the case with Britain in the 1970s and India in the 1980s) or by unsustainable external funding (as was the case with Indonesia in 1997).

Growing evidence of economic pain in India in Fiscal Year 16 (FY16)

Based on my trips to various parts of India (Delhi, Lucknow, Patna, Hyderabad, Pondicherry, and rural Maharashtra) over the past three months, and based on Ambit’s economic analysis, it seems reasonably clear that the PM’s resets are now beginning to bite as:

The real estate sector faces a broad-based multi-city pullback in prices (down between 5-20% YOY—year over year—in most Tier 1 & Tier 2), in transaction volumes (down by over 50% cumulatively over the past three years) and in new launches (down by 50-80% YOY). Note that real estate capital expenditure accounts for between 10-15% of Indian GDP and that over the past ten years, one in three non-agri jobs in India have come from this sector.

The rural economy faces unprecedented distress caused by lower subsidies (9% budgeted drop in subsidies in FY16), low hikes in Minimum Support Prices for three years in a row, a complete stagnation in land transactions and growing joblessness amongst rural migrants working on urban construction sites, all of which is dragging down rural wage growth (5% now vs 15% a year ago). Note that rural consumption accounts for around 25% of Indian GDP.

Private sector capital expenditure is not increasing since: (a) crony capitalists see lower scope for supernormal profits under Narendra Modi; and (b) less corrupt capitalists don’t see any reason to invest in a country characterized by surplus – often stranded – capacity in almost every sector.

Hence, I believe that GDP growth in FY16 will be lower than the 7.3% clocked by India in FY15. As this becomes evident over the coming months, I reckon consensus will have to sharply scale back its expectation of 7.8% GDP growth and double-digit Sensex Earnings Per Share (EPS) growth in FY16. If contemporary India follows the robust template for economic reform established in other economies, such a scale back in growth expectations is more likely than not to be accompanied by a pullback in the Sensex.

Saurabh Mukherjea is CEO – Institutional Equities, at Ambit Capital and the author of “Gurus of Chaos: Modern India’s Money Masters”. He writes here in his personal capacity.