Indian Democracy Has Deeper Roots Than Faux Liberals Are Willing To Admit

If at all democracy is in danger, it is from those who think it is their personal property, delivering outcomes that they like.

For the rest, democracy works just fine.

On Thursday, 19 November, I participated in a debate where the proposition was “Indian democracy is in danger.” Speaking for the motion were Shashi Tharoor, Congress Member of Parliament, and Mallika Sarabhai, dancer, and against it were Shazia Ilmi, a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) member, and Yours Truly. (You can watch the whole debate here)

The debate was lively and both sides made good points, but what appalled me was the starting vote, where 83 per cent of viewers agreed that Indian democracy was indeed in danger. By the end of the debate we were able to convert only 9 per cent of the 83 per cent to believe that Indian democracy was in no imminent danger.

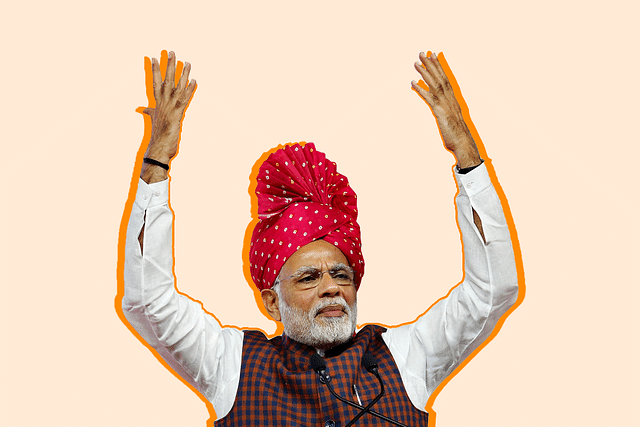

Clearly, the average upper class Indian – the only kind that attends litfests, and this one was Tata Literature Live – has bought into the mainstream narrative that Narendra Modi, his party and his wider Parivar are a threat to democracy.

Given the format of the debate, where each speaker got seven minutes to say his or her piece, and two minutes to rebut the opponent later, it was not easy to make my points in full. All I could do was summarise my broad arguments in bullet points.

In order to expand on my theme that democracy was not in any greater danger today than it ever was, given below is an expanded version of what I wanted to say. (I have put the shorter, bullet-point version, at the end, since these words were what I got to speak at the Tata LitFest).

So, here goes.

I have often found that those who shout loudest about saving democracy are probably some of its ill-wishers. The arsonist is the one who is most likely to shout “fire” since it deflects suspicion away from him. Countries that are most undemocratic put “democratic” and “people” in their official names.

Examples: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea), and People’s Republic of China (Xi Jinping’s fief). The truly democratic countries get by with simple names like Republic of Korea (which is South Korea), or Republic of China (which is Taiwan), or Republic of India.

Whose Democracy Is Threatened?

So, when my erudite rivals in the debate claimed that democracy is in danger, the two questions we need to ask are: who or what constitutes a danger to democracy? And whose democratic rights are they fighting for?

If you are fighting for democracy of the elites, by the elites, for the elites, especially those living in Delhi’s gated Lutyens zone, sure they will find that other voices are now beginning to be heard above theirs. Their right to talk on behalf of everyone else is gone.

The democratisation of free speech that came with the rise of social and digital media has given voice to the voiceless millions over the last decade, and this sounds like the death of democracy when viewed from the gated balconies of the elite.

It is interesting that people who always talk about giving the subaltern a voice are now threatened when a genuine subaltern leader, backed by many sections of society including subalterns, has come to power through democratic means, and not through a violent revolution. The fight against inborn privilege is being seen as a threat to democracy.

In fact, despite some aberrations where the state and thin-skinned politicians target free speech and democracy, I would have thought that we face the opposite threat: not a real threat to democracy, but an excess of democracy, where free speech rights are used to abuse and threaten others and cause social tension.

Free speech is being used to cause a civil war, whether on the basis of our caste fault-lines or religion. Even as we debate the dangers to democracy, the Supreme Court is asking the government to frame laws to supervise and censor what is being said on various media platforms, especially social media.

One high-profile media editor went to jail for his aggressive comments on some issues, thanks largely to “defenders of freedom”, which include Tharoor’s own party in Maharashtra. Another one (Sudarshan TV) has been stopped from going ahead with his broadcast that allegedly targets one community. Defenders of free speech and democracy are on the side of those who want to gag people, allegedly for hate speech when hate speech has not been defined normatively.

So, my first claim is that it is the elites who think their voices are being drowned by the cacophony emerging from social media, and second, that overall democracy is actually on the ascent, and the aberrations, if any, relate to some people going bonkers with their new-found free speech rights on social media. We need to temper them rather than censor them, but that is another story. Democracy has never been in ruddier good health.

India’s Democracy Is Rooted In Its Soil; It Is Not A Gift Of The Constitution

Some people never get this, but India is democratic not because of what the Constitution mandates us to be but because of who we are as a people. Indian democracy has deep roots in the innate pluralism of Hindu/Indic religious and philosophical thought, where difference and diversity never made us uncomfortable as a people.

Democracy cannot be guaranteed by a synthetic and borrowed Constitution, however nice it may sound in drawing rooms; it needs a fertile soil in which it can germinate, and India provides that soil.

Amartya Sen wrote about the Argumentative Indian to emphasise that dissent and democracy were rooted in Indian heritage. This is why those who broke away from this tradition, like Pakistan and Bangladesh, and even our other regional cousins in Afghanistan, Myanmar and Sri Lanka, have dabbled with authoritarian ways. India has largely avoided that path.

It is customary to mention Indira Gandhi’s Emergency in the context of our authoritarian impulses, but I would like to point out its redeeming feature: there was absolutely no need for Indira Gandhi to hold an election in early 1977, but her Indian DNA would not allow it.

She knew that without electoral legitimacy, she had no right to rule. That brief diversion into authoritarianism was quickly corrected, and this was the result of her Indian DNA telling her what was the right thing to do.

Looking back, we must applaud the Indian democratic spirit that finally guided her to the right path, and not the aberration that took her away from it.

Why India Is Fertile Soil For Democracy

The reason why India’s soil will never accept non-democracy as the norm is simple: it is our oldest heritage, starting with the Rig Veda. None of the three major religions that developed roots in India emphasise exclusivity or exclusion.

They fought, they debated, and they compromised. Indian religions are characterised not by belief but a search for higher truths, and reasonable doubts are privileged over established truths given in some holy book or pronounced by a prophet. This is in contrast to the certainties of alleged universalisms. This idea is found in the creation hymn of the Rig Veda, the Nasadiya Sukta, which Tharoor quotes in his book, Why I am a Hindu.

One part of the verse runs something like this, though there are several translations of it. It should be seen as the agnostic’s anthem, someone who raises reasonable doubts.

…Who knows, and who can say

Whence it all came, and how creation happened?

the gods themselves are later than creation,

so who knows truly whence it has arisen?

Whence all creation had its origin,

the creator, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not,

the creator, who surveys it all from highest heaven,

he knows — or maybe even he does not know.

The key points to note in this creation hymn is speculation about the creator, his creation, and how the world came into being. This is the right attitude for a seeking mind rather than a believing mind, where the world is said to have been created just 4,000 years ago.

Democracy flows from pluralist thought processes, and Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism are the oldest practitioners of this art of pluralism, argumentation and introspection. There is an acceptance of god, or one can create one for one’s own psychic needs, and there is also a willingness to see beyond the idea of god to humanism.

Where Liberals Went Wrong With Universalism

Pluralism is the heartbeat of Indian democracy, and it can never wither away as long as the Indic thought process is not eradicated by millenarian ideologies that promise universalism but end up giving us a cancel culture (my way or the highway, my god or the devil) where intolerance is the norm.

Political incorrectness is a thought crime, punishable by the Left-liberal cabal. Liberals, who should be the pillars of democracy, became a dying breed the day they sold their souls to the Left, which favours dictatorship over freedom. The most illiberal ideas and mass murderers came from the Left, and liberals signed their death warrants when they allowed themselves to be hyphenated with the Left.

If at all Indian democracy needs saving, it should start with liberals dehyphenating themselves from the violent and intolerant Left. But thus far we see no signs of this dehyphenation.

And yet, many famous Indians don’t understand why India remains a democracy, while its neighbours swing in the other direction. One famous central bank governor who is the darling of liberals in India wrote this passage some time ago.

“In India, the caste system ensured that entire populations could never be devoted totally to the war effort. So, war in India was never as harsh as in China. At the same time, the codes of just behaviour emanating from ancient Indian scripture have historically constrained arbitrary exercise of power by rulers. As a result, India’s governments are rarely autocratic. History is not destiny — but it is influential, and it is a perpetual puzzle why India has taken to democracy, while some of its neighbours with similar historical and cultural pasts have not.” (Bold words are mine).

I have quoted this text at some length to show why liberals do not like the conclusions their own reasoning leads them to. After explaining why Indian governments are “rarely autocratic”. Raghuram Rajan – that’s his quote – says Indian democracy is a “perpetual puzzle” to him. Why are liberals so wary of recognising the inherently democratic and plural character of Indic philosophy and culture?

To be sure, we have made big mistakes with caste, but which country has adopted a multi-generational, open-ended affirmative action programme like the way India has to uplift its oppressed groups? While the US is still to end its racial divides more than a century-and-a-half after abolishing slavery, India in less than half that time has made progress on reducing the worst excesses of caste.

We still see eruptions of caste violence, and these constitute a blot on our collective conscience, but we need to contrast these eruptions with the enormity of India’s diversity – 1.4 billion people, speaking a multitude of languages, following various religions, and confronting the enormous challenges of poverty, illiteracy and external threats from intolerant ideologies. India faces two rogue nations on its borders, and not just the one we have lived with since Partition.

The Upcoming Threat To Democracy

That said, does Indian democracy face some threats? Yes, and those threats relate to the power of tech platforms like Facebook, Google and Twitter, which are now brazen enough to censor those they disagree with. They can even go to the extent of censoring the President of the US, even though he may not be everyone’s idea of a worthy leader. Tech platforms practice cancel culture with a vengeance. They need to be regulated and held accountable for what they do or don’t do.

Where We Went Wrong In Our Constitution

The other real worries which stunt our democracy are two mistakes we made in our Constitution. The “last Englishman”, who happened to become our first Prime Minister, adopted the British parliamentary system and the first-past-the-post system, which ensures that even those who win elections do not have a broad enough mandate.

Some people started talking about this only when Narendra Modi got a majority with 31 per cent of the popular vote in 2014, but the problem is parliamentary democracy itself. This system suits a two or three-party country, but not one with extreme diversity and scores of political parties.

The first-past-the-post system ensures that a mandate comes with anywhere between 31-35 per cent of the popular vote, whereas a two-stage presidential system as in France would ensure that the ultimate winner has the backing of at least 50 per cent of the voters. Funnily, those who talk about democracy being in danger are also the same people who oppose the shift to a presidential system.

A presidential system backed by a legislature that is elected through a proportional representation system (with minimum vote cutoffs like in Germany and adequate safeguards to prevent fragmentation and unviable coalitions that retard progress) would have served India better. It would be inclusive, and yet would not result in a governance deadlock of the kind we see repeatedly whenever we end up with unmanageable coalitions at the Centre or states.

The second problem which retards our democracy is weak state capacity. From the time of independence, our politicians have privileged the provision of private freebies over public goods like law and order and good quality universal education and healthcare.

Thus, the police the judicial system have become a law unto themselves, constraining the exercise of democracy by the people. In which democracy do you see the judiciary appointing its own judges, or being empowered to make the law, and not just interpret it? Some time ago, the Supreme Court actually imposed taxes on SUVs entering Delhi in the name of curbing pollution, when taxation is nothing to do with the courts. An unreformed police-legal-judicial system is a threat to democracy.

These are structural problems with Indian democracy, and till these are fixed, our problem is not democracy, but its flawed institutional structures. If at all democracy is in danger, it is from those who are supposed to defend it and reform its institutions, but that is not happening.

The Problem With “Liberals” Crying Wolf Too Often

To conclude, let me repeat the story of the boy who cried wolf. Once, just to check if the villagers would turn up if he cried wolf, he found that his call was answered. The villagers rushed with sticks and stones to drive it away – but found no wolf waiting for them. Then it became a sport with the boy, and he cried wolf just for the fun of seeing villagers rush to action. But one day when the wolf actually did come, he cried wolf and no one came to the rescue.

This is the real problem with those who cry “Indian democracy is in danger.” If Narendra Modi wins an election, democracy is in danger, EVMs are doctored. If a judgment goes against what some liberals want, again democracy is in peril. If India bombs Balakot or conducts surgical strikes, it is the credibility of the government that must be questioned, for, after all, these things are done only to burnish the image of the presiding Hitler.

An RBI Governor can talk about Hitler and one-eyed kings and generally irritate the government with his quasi-political comments – something which no other central banker does – but when his contract is not renewed at the end of his term, again democracy and institutional independence are seen to be compromised.

For our liberals, the judiciary is compromised because it won’t always oblige them, the Election Commission is beholden to Modi because it won’t shift to paper ballots, the RBI has sold it soul since it wants to work with the Finance Ministry to lift the economy out of the ditch. If this is not crying wolf, what is?

If at all democracy is in danger, it is from those who think it is their personal property, delivering outcomes that they like. For the rest, democracy works just fine, thank you. I rest my case.

Given below are the seven points I made during the debate. They summarise some of the points above.

First, Indian democracy has deep roots and is not based on what some farsighted leader bequeathed to us or what is written into the Constitution. Democracy flourishes in India because its soil and culture are supportive of it. Our problem may be the exact opposite – of reining in excess of free speech and gross indiscipline that leads to anarchy.

Second, our secularism is a sham – pluralism is our natural rhythm. I am not indulging in mere semantics here. Secularism evolved in Europe where state and papal authority were in conflict. Both wanted sovereignty. They solved the problem by separating church from state, but here’s the thing: both retained separate autocratic power over the same person, the individual.

Thus, the individual becomes a schizophrenic, learning to live with two bosses. This is fundamentally problematic. The prophet of Islam realised that the individual is complete in himself, and needed holistic support. He was religious leader, military chief and political boss all in one. Not for him the pretense that state and religion are separate.

In India, we are comfortable living in shades of grey. The average Indian knows that his identity is not determined by the temporal or religious authority. He decides it himself.

European secularism is thus an artificial construct. Pluralism is what makes sense for India. Pluralism is about learning to live with difference and diversity, and these differences relate not only to religious identities, but every other form of difference, whether of caste, race, or language. Secularism is a limiting idea for India.

Third, the threats to democracy come from its alleged defenders, and not from the alleged threat of majoritarianism or Hindutva. Hinduism is not a fundamentalist creed; it is diverse by nature and inclination. It does not derive its truths from one historical figure or one text. It is inherently non-majoritarian since it has no fundamentalism to defend.

Fourth, our democratic institutions are ill-suited to the Indian genius and attitudes. In particular, our parliamentary democracy is wrong for us. We need a presidential system, backed by a legislature that is populated largely through proportionate representation. Both tend to be more inclusive than a first-past-the-post system where parties can get a working majority with anywhere from 30-35 per cent of the popular vote.

Fifth, if democracy is under any threat, it is not in Delhi, nor did the threat emerge only after 2014. Our problem – which is largely a media problem – is an excessive focus on what the government at the Centre does, but its actions are fully scrutinised not only by the mainstream media, but also global media. It is the mini autocrats that rule the states that go under the radar, and our liberals don’t care what happens there unless they are BJP-ruled states.

Sixth, right from the Nehruvian era, we invested in private goods like freebies and subsidies, but not public goods like law and order, universal education and healthcare, and good infrastructure. These gaps are being remedied now, but these wrong priorities flowed from the top-down, unaccountable political system that we have.

The judiciary more or less appoints itself, the police derive their support not from the law but politicians temporarily in power, and the bureaucracy is a law unto its own. We need to reform all these institutions in order to have a more robust democracy.

Seventh, our tendency to cry wolf too often, when there is no wolf visible. We may thus fail when the wolf actually arrives and we are unprepared for it.