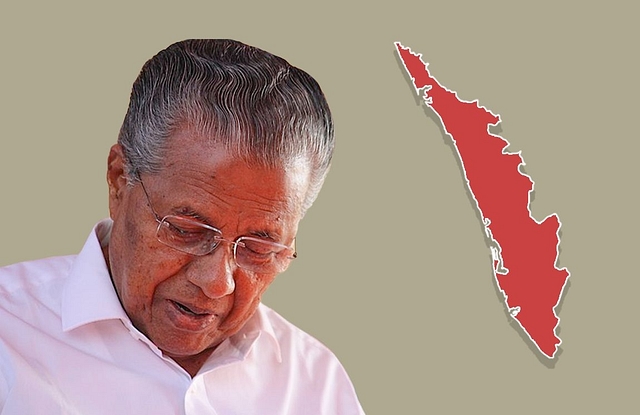

Is Kerala Headed For A Major Political Upheaval?

Though there is no one answer to where the major developments in Kerala politics are headed, the present mess seems to be a mixture of multiple factors, and here are half a dozen of them.

Politics in Kerala is notoriously arcane even on a dry day. Now, it seems set for a major, generational realignment, which has the potential of confusing matters further. The opposition Congress-led United Democratic Front (UDF) and the ruling Communist Left Democratic Front (LDF) may soon swap traditional alliance partners as the state gears up for assembly elections in May 2021.

This is the admittedly-fluid and confusing situation as on date:

The Kerala Congress (KC), a UDF ally, led by political dynast Jose K Mani, which commands a majority of the Christian vote in Kerala, is mulling a shift to the LDF. The Communist Party of India (Marxist), the CPI-M, expects its enticements to be fruitful. (To clarify, the KC has a tendency to splinter periodically. As a result, the ruling LDF coalition already has a few one-man factions formerly of the KC in its ranks).

The Communist Party of India (CPI, and not to be confused with the CPI-M) may ditch the Left and move to the Congress side.

The CPI was the original party unit until it split in 1964, after the Sino-Indian war (not least because the CPI-M’s V S Achuthanandan, later Kerala chief minister, ran a blood donation drive in support of our troops).

It remained the ‘Big Brother’ under C Achutha Menon, and successfully ran governments in the 1970s, along with the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) and the Congress.

It withered over time to become a junior player, and went back to the Left fold in the 1980s, but the CPI still retains a meaningful presence in about two dozen seats in the state. That’s a key edge amidst an electorate which decides fortunes by 2-4 per cent vote margins.

Intra-alliance bickering had been growing for some time now, but matters came out into the open only this weekend. The CPI’s Kerala chief, Kanam Rajendran, indirectly referred to Jose K Mani as a virus by advocating ‘social distancing’ from the Christian KC party (still on paper with the Congress, but no doubt, actively considering a left turn). It was a warning to the CPI-M, offered with all the nuance and subtlety one expects of the Left.

Kodiyeri Balakrishnan, the CPI-M’s state party head, shot back at the CPI with a lesson in history, by asking the CPI’s Rajendran to recollect how poorly his party had fared after the infamous 1964 split in the 1965 assembly elections (the CPI won a measly three seats, contesting on its own).

Rajendran of the CPI retorted with a zinger, by asking the CPI-M to recollect in turn, a time when the CPI-M had aligned with the Muslim League (as if that was anathema to a CPI, who themselves had no compunctions in forming a government along with the League when needed).

Into this fracas rode the RSP – the Revolutionary Socialist Party; once a staunch Left party under the legendary Baby John, then not with the communists, then with them again, then a motley, fragmented crew with disparate political moorings, then, since the past few elections, with the UDF, more vociferously Congress than the Congress, and, hold your breath, definitely not to be confused with the RSP (Leninist), who are a splinter faction firmly with the LDF.

In a press conference on Sunday (5 July), the RSP formally invited the CPI to leave the LDF and join the UDF.

Lok Sabha Member of Parliament, N K Premachandran (who can be routinely seen out-snarling his Congress bench-mates in Parliament, and was memorably trounced by the late Sushma Swaraj in debate), made a longwinded offer of welcome to the CPI. But it was his party colleague, Shibu Baby John, who provided the star turn by elegantly reminding the CPI of how things had once been.

This former MLA, son of RSP founder Baby John, and minister in the last Oommen Chandy government, asked the CPI to remember how well the Congress, the Muslim League and the CPI had worked together in power, in a ’golden decade’ from 1970-80, under C Achutha Menon.

The messaging couldn’t get any more direct. But the question is: where is this major development in Kerala politics coming from, and where is it headed?

There is no one answer, but this present mess seems to be a mixture of multiple factors:

First, communist Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan’s shoddy handling of the Wuhan virus epidemic has led to a situation where, instead of flattening the curve, he’s flattened the state. Case counts are rising, as are contact transmissions; testing is abysmally low; and contact tracing of individuals is not progressing as needed.

Commerce is at a near-standstill, and state revenues are fearfully down. The state is broke. For all his tall talk of a ‘Kerala Model’, Vijayan has become a liability to the CPI-M, but one they can’t let go of. That has grave electoral consequences.

Second, the CPI senses this acutely; that the CPI-M has alienated large sections of the state, and will attract further public ire in the build up to next year’s assembly elections.

Third, Vijayan and the CPI-M know this too. That is why they are out to woo the Christian KC.

The communists don’t stand a chance in a three-way split, if they don’t attract a chunk of the minority vote.

Fourth, the KC and a significant section of the Christian vote could be shifting from the UDF to the LDF, partly because of a universally negativist Congress stance, be it on the epidemic, the Citizenship Act, or Sino-Indian relations.

Nobody likes to be stigmatised, especially not minorities, and definitely not by association – which is what is happening thanks to the prevailing Congress-led narrative.

Fifth, it is possible that that this migration by the KC, if it happens, could be the first leg of a longer shift towards the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Already, acceptability of the BJP within the Christian community in Kerala is growing, with the BJP having put up a number of Christian candidates in the last few elections. P C George, a sitting independent MLA, is an official alliance partner of the BJP.

Sixth, the unspoken fear of both the LDF and the UDF in Kerala, and the real reason for the present crisis, is the gradual shifting of the Hindu Other Backward Class (OBC) Ezhava vote from the Left to the BJP.

Thus far, the Left had banked on the Ezhava vote, plus a smaller section of the minority vote, to regularly win elections handsomely. But now, that open, divisive anti-Hindu narrative, which the Left actively promotes, has begun to erase old divides, and bring back an integrative, collective identity which transcends Marxist caste prejudices.

If that happens, the CPI-M is finished, and the LDF with it. This is the crux, the actual electoral danger, which the CPI recognises, and why it is considering an alliance with the Congress.

In a nutshell, the 2019 general elections clearly showed that the Congress and the UDF are unbeatable in Kerala, as long as they get the minority vote, and the BJP stays stuck under 20 per cent of the vote share.

The Congress doesn’t need Hindus to win in Kerala. But, if the Christian vote shifts even in part to the Left, and the Hindu vote shifts from the Left to the BJP, then the Congress and their allies are looking at potential disaster, except in those few seats where the minority is in a majority (like Waynad).

What’s also interesting is that none of the proposed alliances are inconceivable, and neither are they new. At some point of time in the past, everyone has aligned with everyone else: communists with the Muslim League, socialists with the Christians, Bolsheviks with the Bishops, and everyone against the BJP.

Decade after decade, Hindu votes were split like a Chinese fan, and minority votes were assiduously consolidated, to fashion successful electoral formulae of near-perfect vote-banking.

The problem is what to do when the Hindu vote finally commences a supra-caste consolidation under the BJP? Different parties have different answers, and that is what is happening in Kerala today.

It appears that both the UDF and the LDF finally comprehend the existential nature of these present times in Kerala:

One, for multiple reasons, including the mishandling of the epidemic, Pinarayi Vijayan and his CPI-M have performed poorly enough for the BJP to envisage improving their position considerably in 2021 (more, if the BJP identifies and grooms a popular Ezhava leader soon).

Two, efforts by the CPI-M to counter that, by allying with the Kerala Congress, could split the minority vote in places. That in turn would create a genuine three-way contest, especially if a part of the Hindu vote bids the CPI-M adieu, and counterproductively end up aiding the BJP and its National Democratic Alliance (NDA) allies. Strange as that may sound, it’s actually a possible outcome in at least a dozen seats.

Three, any efforts by the Congress-led UDF to counter that, by aggregating the minority vote under its banner, would ironically, only accelerate a counter-consolidation in the BJP’s favour.

Four, either way, the CPI-M gets squeezed.

Five, everyone stands to lose, whatever the permutations and combinations, except the BJP.

So, it’s a tricky situation, and we will have to wait for the realignments to concretise, before numerical, electoral outcomes are estimated.

Yet, if the UDF’s RSP has already started dreaming openly of a ‘golden decade’, arm in arm with the CPI, and goodbye to the KC if need be, then they should also remember that this is equally, a golden moment for the BJP.

Every coin has two sides. In any case, political ideology died a long time ago in Kerala; at least now, it is being given a proper burial.

Of course, it would be impolite to conclude without studying the national ramification of a split in the Left. What happens if the CPI and CPI-M part ways?

Considering their vote shares, the best we can predict is that Daniel Raja of the CPI will no longer enjoy the privilege, of standing shoulder to shoulder with Sitaram Yechuri of the CPI-M, while clapping along to azadi chants at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Now wouldn’t that be sad?