Is There A Need For Caste-based Census In Tamil Nadu?

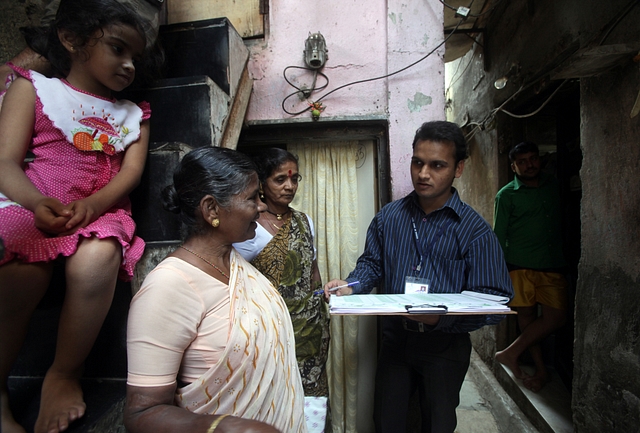

Ravindran Duraisamy contends that the grievances of communities cannot be assuaged without a caste-based census and following a rigorous approach to distributive justice.

However, if caste census is the answer, there has to be an honest assessment of the pros and cons of such an exercise. Also, in the absence of statesmen, who will champion it in the minefield of the Tamil politics?

Noted political analyst Ravindran Duraisamy has been ruffling feathers in Tamil Nadu by openly lamenting that the land of Periyar is in fact a land of social injustice. His contention is that the basis of community-based reservation is not scientific and is based on uncertain statistics, with some caste groups enjoying disproportionate benefits, while others are being left in the lurch. He calls it “ransacking of social justice”.

Duraisamy notes that the current architecture was carved out by the political activism of major groups and the whims of leaders. In a recent commentary on the Nadar community, he traces the history of the community that successfully agitated to get itself de-listed from reserved communities in 1931 and later got itself enlisted into the Backward Communities (BC) section only in 1963.

Even among them, Christian Nadars got added to the BC list only in 1983 due the electoral compulsions of the then chief minister, M G Ramachandran. In the normative sense, without saying as much, he pleads for a deontological approach to the issue.

He also goes on to list the communities of similar or lesser social standing and how they have not reaped the benefits of reservation. They are smaller and dispersed communities and hence have been unsuccessful in drawing attention towards their needs. He is particularly scathing about former chief minister M Karunanidhi who scuttled the Venkatakrishnan Committee that was formed for conducting caste-based census.

Duraisamy contends that the grievances of communities cannot be assuaged without a caste-based census and following a rigorous approach to distributive justice. This need for caste-based census has been put forward over the past decades by many leaders including Paattali Makkal Katchi’s (PMK’s) S Ramadoss and Dravidar Kazhagam’s Veeramani.

Electorally what is derisively referred to as social engineering was used as a tool to empower and garner support of electorally significant communities. One can write tomes on caste agitations and electoral politics of India — the famous ones being the politics of Samajwadi Party (SP) and Bahujan Samajwadi Party (BSP) in Uttar Pradesh (UP).

A downside of this was the disempowerment of the backward but electorally insignificant groups. While the issue has existed for a long time, it was Amit Shah of the BJP, who — as the helmsman of Uttar Pradesh in the elections of 2014, 2016 and 2019 — showed extraordinary creativity in stitching together a coalition of smaller communities and thereby politically empowered them.

The stunning electoral victories have blinded analysts from looking deeply at it through a prism of positive social justice. A pertinent question would be to ask whether the BJP can replicate this model in Tamil Nadu by bringing together assorted small groups under its umbrella. A strong acceptable leader is a prerequisite for such a strategy to work.

Our liberal approach towards caste — through affirmative action in employment and education and tough laws against discrimination — is based on the premise that the rough edges of caste in the public sphere will smoothen out over a period of time.

Though honour killings still appear in the news, and clashes between castes continue, and caste identity obstinately persists in being the most important marker of a person’s social standing, one can still argue that the virulence has come down overall. But our attempt to blunt the edges and lull the people out of caste consciousness has not been able to bury it.

If caste census is the answer, there has to be an honest assessment of the pros and cons of such an exercise. Also, in the absence of statesmen, who will champion it in the minefield of the Tamil politics? The shaky fourth pillar offers no hope of being a fair arbiter of the debate either.

Both Karunanidhi and Jayalalithaa had the political stature and clout to keep the tenuous equilibrium. With their demise, deeply buried grievances may rise up. Political entrepreneurs may position themselves to be lightening-rods of such emotions and want to champion the case of a caste census.

The attendant risk in the exercise is the deepening of caste consciousness in the society. The liberals among us would argue that it would undo decades of gains and make the relatively progressive urban Tamil society discard new markers of statuses in education and wealth.

It would be hard for a national party such as the BJP to champion such a census without jeopardising the delicate caste balances in other states. It may also not sit well with the ideology of rising beyond caste, which they believe has been the main instrument of division of the larger Hindu community.

The entrenched old parties, Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (ADMK) and PMK, have become dependent on the communities that back them electorally. The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) that is desperate to grab power, and having anointed a timid leader, could not be expected to take it up either.

This opens up the space for new political actors like Seeman and Kamal Hasan (and Rajinikant, if and when he comes) to become vanguards of this debate.

Prime Minister Modi changed the rules of the old game when the government enacted 10 per cent reservation based on economic criteria for hitherto unreserved sections. One can argue that it came on the back of defeats in the assembly elections of December 2018 but it has nevertheless opened avenues of Social Justice 2.0 based on economic status. The political class in Tamil Nadu is divided over the move lest they anger their voting groups.

It is not impossible to imagine a 50 per cent allocation for reservation, applying creamy layer restrictions on the reserved quota based on economic status and leaving the rest to merit-based candidates. While technology is gradually making reservations in education irrelevant, reservation in government jobs has obtained added attraction in the times of patchy economic growth and technology-based disruption of the labour market.

We can wring our hands in frustration at our collective inability to solve many vexing social issues in the 72 years after independence. If we had resolved the issues, it could have given the current generation an opportunity to focus on working without distraction towards prosperity and geopolitical success. But the sobering fact is that society is always “under construction”, especially a complex one like ours. There is no end to tinkering around the edges. However, the endeavour towards a lasting solution should never cease.