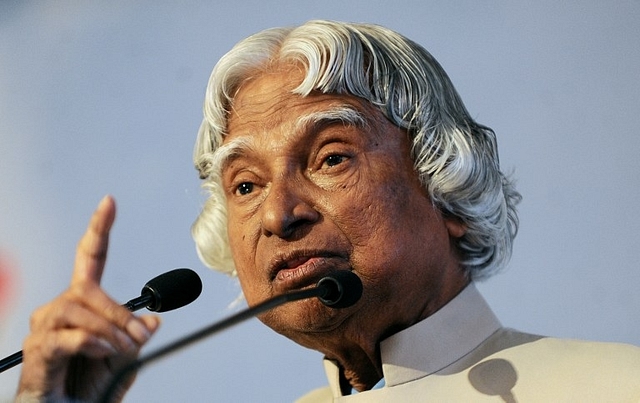

Kalam: Sacredizing The Secular

In the long line of India’s nation builders, Kalam makes Nehru whole and complete.

When Dr. Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam first brought out his vision for a developed India ‘India 2020’, he was making a strong case for the development of the secular dimensions of the national life. The book dealt primarily with the food, agriculture, chemical industries, space, satellite, communications, energy, biological resources, etc. One can even say that Kalam was advocating what can be called as the quintessential Nehruvian vision for the nation, but then, in page 275 of that 1998 edition of the book, ‘India 2020’, one finds a concept radically different from what Nehru envisioned for India. Here Dr.Kalam spoke of a golden triangle:

“Our job is to make this golden triangle of punyatmas, punyadhikaris and punyanetas work countrywide so that a lot of actions can be initiated and promoted at the grassroots levels.”

Three years later in 2001 when talking to Pramukh Swami Maharaj of Swaminarayan Sansathan at Ahmedabad he reiterated the idea again:

“To realize this great dream, three types of people are needed punya atma (virtuous people), punya neta (virtuous leaders) and punya adhikari (virtuous officers). If the population of all the three were to increase in our society, then India would become the jagadguru.” (Ignited Minds, p.43)

For all that his detractors may say about Nehru, he wanted a developed India. In that, he was completely selfless. But he lost himself in the romance of borrowed ideologies. He never valued the strengths of his own soil. Yet he desired India’s technological independence and a host of science personnel took advantage of that ambition. It was how Indian scientists succeeded in creating some very enduring institutions of science during the Nehruvian era.

Yet, it should be noted that both, the Bose Institute of Science and the Institute of Science created by Tata owe it not to the obsessive compulsive secularism of Nehruvian type but to the Vedantic spirit. Going through the writings of Nehru, one does find that he understood somehow that his vision was lacking some important ingredient. He was honest enough to accept that ‘secular philosophy itself must have some background, some objective, other than merely material well-being. It must essentially have spiritual values and certain standards of behaviour, and, when we consider these, immediately we enter into the realm of what has been called religion.’

Perhaps, had he lived long after the Communist backstabbing of China war, he would have become a changed man – who made himself whole by including the sacred catalyst in his vision of secular progress – something that one finds in Rajaji. Perhaps he would have overcome his obsession with socialism and would have appreciated the importance of entrepreneurship in making India prosperous, increasing the common good of all. Perhaps he would have seen Indian religious institutions having the capacity for contributing to the growth and development of the nation and society. But his death came too soon.

And then Kalam came.

He went to all religious places and talked how their works are closely connected to the development of the nation. He developed the rapport with the younger generation. At a time when the nation saw the complete failure of Gandhi-Nehru model, Kalam came and showed the nation that the model was not completely wrong but that it lacked something essential. That essential thing is Punya : not as a concept of bygone eras but as an existential reality that can catalyse the technologies towards the common good of all humanity.

His greatest joy came when through his innovation, ISRO’s technology provided materials for the production of calipers for the differently-abled children which reduced the weight of the caliper to 1/10th of the original weight. The Kalam-Raju stent reduced the cost and dependency on foreign stents by Indian cardiac patients. Kalam gave us the technology with the heart of Punya. When he delivered his first speech on assumption of the office as President of India on July 25, 2002, he quoted both Thiruvalluvar and Kabir – both poets, and legends say they were both weavers, too. The son of the boatman from Rameswaram was weaving in his speech the cultural nationalist unity of India – something again amiss in much of Nehruvian discourse, though not completely absent.

At the same time, he was also a realist. He encouraged India’s nuclear programme. He was the missile man who gave new India one of its greatest mantras: ‘Strength respects strength’. Unlike the Nehruvian peace ballads which got short-circuited by harsh realities, Kalam’s longing for peace never yielded an inch in India’s self-respect.

In a way in the long line of India’s nation builders, Kalam makes Nehru whole and complete. And it will be the magic of great Indian Dharma when Narendra Modi, who comes from the family of Hindu nationalism, realizes the Nehruvian vision of real regional peace in South Asia through the doctrine of Kalam: technological self-reliance and an assertion of the indomitable spirit of India.