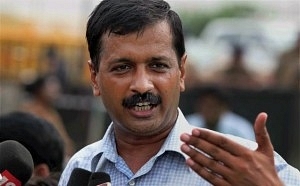

Kejriwal Talks Delhi, Eyes Rural India

Announcing a huge compensation for farmers in a city that is hardly left with farmlands cannot have any other political meaning.

Politicians are the same all over. They promise to build bridges even when there are no rivers.

— Nikita Khrushchev

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s recent announcement of a handsome compensation of Rs 20,000 per acre (Rs 50,000 per hectare) to Delhi’s farmers who have lost their crops to untimely rainfall since January this year is certain to have brought a lump in the throats of many of his die-hard fans.

Addressing a gathering over the weekend in Outer Delhi’s Mundka area, bordering Haryana, the Delhi chief minister said, “I am told that this is the highest ever compensation in the country… This was necessary… Governments have made such policies that nobody wants to be a farmer any more. It was important to send a message to the rest of the country.”

However, as with most of his moves since his India against Corruption (IaC) days in 2011, is Kejriwal once again trying to market a bigger message to the India that exists beyond Delhi or its other major metros? Or, as the first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union bluntly put it, is he trying to achieve that goal by building a bridge in a place where, figuratively speaking, much less a river, only a stream is left?

For, however noble the announcement might look superficially, numbers released by the Delhi government tell a different tale. Most of us, with a decent knowledge of urban India, know that the capital city is a rapidly expanding concrete jungle with negligible farm holdings left.

According to Delhi’s Economic Survey for 2012-13, page 139 (no data in public domain for 2013-14 and 2014-15):

As per village records, the total cropped area (in Delhi) during 2000-01 was at 52,816 hectares, reduced to 36041 hectares in 2005-06 and in 2012-13 was to tune of 35178 hectares. The reduction of cropped area during this period was worked out at 2.57 per cent per annum. Simultaneously the percentage of cropped area from total area was reduced from 35.81 per cent in 2000-01 to 23.85 per cent in 2012-13. The remaining areas of the Delhi are being used for various other uses such as non-agricultural purposes, forest, fallow land, uncultivable land, etc. The main reasons behind such reduction in agriculture area in Delhi is due to the fast urbanization, and shift in occupational pattern especially during the last two decades. This results in reduction of share of this sector to the Gross State Domestic Product of Delhi.

The same report also points out that, rapid urbanisation is leading to cultivable command area under irrigation being reduced significantly. In the Delhi Master Plan of 2021, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) has proposed complete urbanisation of Delhi. So, forget an increase, this will only result in further shrinking of the command area.

To give you a personal example, when my parents moved from New Delhi to an area in west Delhi in the mid-1980s, one would often come across patches of cultivated fields. In nearly 30 years since, such plots have nearly disappeared. In the same period, those of my friends, whose families were traditionally involved in agriculture and allied activities, have moved on to other businesses such as transport, light manufacturing and real estate.

Moreover, the contemporary agricultural sector in Delhi has evolved differently from the rest of the country. Rapid urbanisation in the city-state has not only resulted in reduction of rural areas, but has also contributed to the rise in the service sector. Consequently, contribution of agriculture and allied activities to Delhi’s GDP has declined from 1.09 per cent in 2004-05 to 0.87 per cent in 2011-12.

As per the 2011 national census, Delhi’s rural population stood at 419,000 (2.5 per cent of the total population of 17 million). Around 25 per cent of the total area of National Capital Territory (NCT), as per 2011 census, was rural and the remaining 75 per cent urban. The number of rural villages in Delhi nearly halved from 214 in 1981 to 112 in 2011.

The number of operational holdings in Delhi reduced from 28,315 in 2000-01 to 19,917 in 2005-06. The reduction in land holdings in Delhi worked out at 5.93 per cent per annum. The reduction of operational holdings by the individual category was highest at 7.5 per cent per annum, while the same in joint and institutional category was at 4.11 per cent and 6.65 per cent per annum, respectively.

The operational area of Delhi decreased from 43,126 hectares during 2000-01 to 33,086 hectares during 2005-06. The reduction in operational area during the last two agricultural censuses in Delhi is estimated at 4.66 per cent per annum. The reduction in operational area of institutional category during the same period was highest at 7.66 per cent per annum. The same in case of individual and joint category was worked out at 6.82 per cent per annum and 3.49 per cent per annum, respectively.

During the last agricultural census conducted during 2005-06, about three- fifths of the operational holdings size was less than one hectare. About one-fifth of the holdings were under the category of small size and the size was in between one and two hectares. Only a marginal percentage of operational holdings that were over ten hectares could be categorised as large. Area operated under agriculture in Delhi was the highest in medium size and it constitutes nearly one-third of the total areas operated.

According to a report in The Economic Times, at the same gathering in Mundka, Kejriwal also urged farmers of Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra etc to demand a better compensation from their state governments. Needless to say, the news was promptly reported by most of the Delhi-centric media outlets without even taking a cursory look at the available hard data.

Therefore, the announcement by the AAP government is essentially dictated by concerns of cultivating vote banks in the hinterlands. The real intention behind it was to send out the message that the party is not just an urban phenomenon, but also cares for and works in farmers’ interests.

For, even as the share of farming to the GDP has consistently been on the wane in post-independence India, it continues to be perceived as an electorally important sector that can make or mar fortunes. With the number of people dependent on agriculture or allied activities for their livelihood at 50 per cent, parties across the political spectrum often initiate steps that make neither common nor fiscal sense.

A friend wryly put it during a discussion on the subject, “Maybe Delhi government in all its sincerity actually intends to compensate residents of Greater Kailash and Lajpat Nagar, who might have suffered damage to their potted plants on account of the erratic weather!”