Life, Death And Those Vicious Games Of Identity

A world in which a label has to be assigned before people decide whether to feel pain for the suffering of another human being is pretty much a broken, beaten, and semi-barbaric world.

It is bad enough that we live in a world where violence is somehow expected to mean something else always. It is always expressed not as itself – a stark horror, but as a bigger statement, a symbol. Sometimes we call it war, as if some noble purpose is being served. Sometimes we call it resistance. Sometimes we call it terror, though increasingly we find that a label that condemns violence as terror will not stick at all times. We live in an age of enforced empathy and reflexive self-relativization. Being liberal somehow means always conceding that your definition of terrorism might be someone else’s definition of a freedom struggle.

That is what passes for liberalism.

There are no absolutes, even when it comes to the horror of violence, that relentless sickness of one human’s assertion over the natural integrity and freedom of another. You cannot even feel the pain of it. It’s not formally illegal, but your enslaved mind and atrophied conscience tells you it is. You buy the poison words that fill our collective discourse, you brush aside the horror of children and elders trapped and burning inside a train, call them not human beings even, but “activists,” members of a “militant fundamentalist group,” “kar sewaks,” a million loaded evasions a decade of activism and corpse-dancing has not faced honestly. You forget their pain, their right to have had a life, and a life free of pain. You remember them only in retrospect, as a footnote to an alleged genocide, where the pain of some, and only some, mattered.

And what of the one who was burned last week in Pune, the boy who was hardly a man?

You look for him on Google, and you find no manifesto, no words left behind to offer op-ed writers inspiration. You find him so devoid of power he has no language of his own, nor a social media presence for the internet generation’s simulated conscience to rise to his memorialization. You find him so powerless, even the identities which were supposed to rescue him from his abject powerlessness do not come to his rescue. “Dalit” does not stick to him, the term that conscience demands we respect as a reminder of how injustice is not an individual quirk but a social problem, a scourge we must all fight. You search for the word “Dalit” on Google News, and you will find several thousand results now about the death of a Dalit elsewhere; but not this one, not this one who was called a Hindu by his killers and just for that reason, killed.

Was that the reason? The pitiably short list of articles that appear when you Google his name seems orchestrated to get you to think more about that question than the actual horror of what just happened here. Was his being Hindu the reason he got burned alive? That is the subtext that drones doubts at you in the few articles that there are. They evade the truth effortlessly. They call him a rag-picker. They frame the whole thing not as an act of murder but as an act of “Hinduization” or Hindu-victimization by a Hindu right-wing group. They confidently quote the police as saying oh, it wasn’t that; it wasn’t that communal after all.

This identity is such a bizarre business, especially when it comes to the media. The way some of the news reports, few such as there are, on Sawan Dharma Rathod’s lynching (and this, by definition was a lynching, an act of supposed punishment for a minor transgression of property rights), the current identity is a lesson unto itself. The identity of the people making the “allegation” that he was killed for being Hindu is somehow made more important than the identity of the people who did the killing, and of course, the man who was killed, a man whose identity ought to have mattered too.

That is the easiest way it seems to decode reality from the media in India today. If a murder is not deemed communal or casteist by the media, you know very well that it was.

But there will be no spectacle around this death, no roll-call of photographable politicians and their embodied eminence following a tragedy around like a stench that serves no purpose at all.

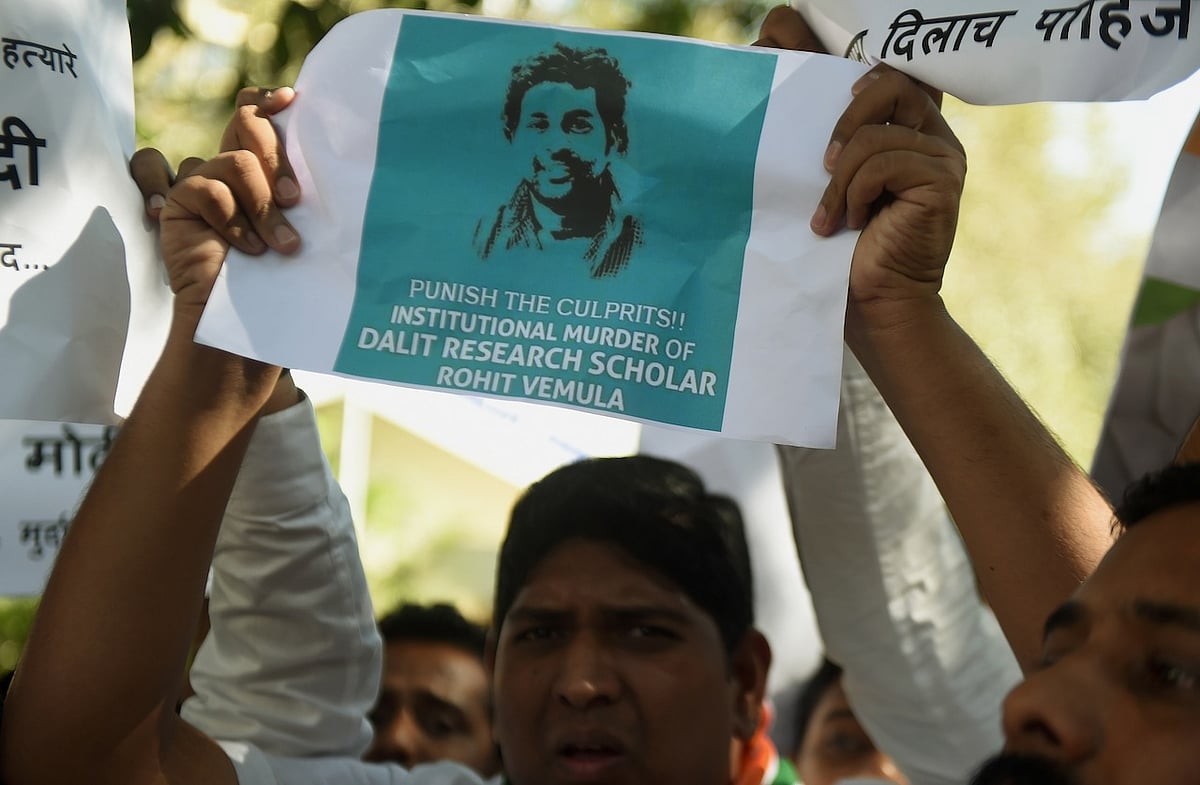

(NOAH SEELAM/AFP/Getty Images)

There will be no introspection about identity, privilege, responsibility, hate, violence, nothing at all.

As Shefali Vidya, who has seen the people in this tragedy from close (though she had no need to do so at all because she is not a politician or a public servant but only a writer and a mother), wrote in Swarajya that one suicide is news, and one murder an item.

The elevation of identity over suffering in the way Indian public discourse is doing of late serves neither the cause of a progressive identity politics nor a campaign against systematic injustice and violence. It is doing to those who have suffered and continue to suffer because of the accidents of their identities what the so-called reality shows have done to reality on TV. They are an ugly, tragic, and poisonous farce, a distraction from our deepest natural faculties as living beings that help us know a murder when we see it. They are tools for a manufactured form of mass ignorance that once sustained foreign colonialism over us and now sustains something, even more, dangerous and toxic.

India must seriously examine its present course of identity politics, and especially its pervasive colonization of our common-sense notions of what it means to be human, Indian, and indeed, decent. The challenge is that in the polarized and simplistic Left-Right framework that increasingly dominates our thinking and draws us ever further away from our richly complex and diverse civilizational roots, identity-warfare has already trapped us into some dead ends. The Left has its menu card of good and bad identities and plays them effectively everywhere. According to its logic, the very existence of some identities precludes them from feeling the pain of others. The Left imposes a postmodern code of censorship on a society that is still largely premodern and doesn’t care one bit for them, for both good and for bad.

The Right, on the other hand, tries to evoke a universal, pan-Indian identity beyond all divisions, partly hoping to restore a pre-divide-and-rule sensibility to the conversation perhaps. But it (or its leadership) mostly ends up sounding like an unimaginative, mediocre, and stodgy imposer of judgments on patriotism and culture and nothing more. If there is one lesson that the ruling party must take out of this, it is to stop going around loosely calling people “anti-national.” You cannot say this simply because a group of misguided students decide to stand in a protest on their campus. You can debate them, you can try and prove why they are wrong, but unless someone is running a weapons racket in their dorm room, you cannot presume to judge them on their patriotism or lack thereof; and you cannot assume most of all that it is a crime. I say this bluntly because there is no other way to break the miasma that identity politics has become.

Frankly, as for the Left, with its convenient cachet of the oppressor and subaltern identities where suddenly people lose their apparent subaltern status merely because they get killed by a group your textbook tells you is somehow even more exaltedly subaltern, in today’s discourse the cosmetic moral high ground is all you have. You are not creating change, not even the knowledge needed to make the change, despite your lofty monopolies on education and the public debate today.

You take in young students whose native wisdom and real-life experience of standing up to iniquity far exceeds your postmodern theories in the first place, and turn them into ciphers of their selves. You fill the young with rage, which when directed against injustice is always welcome, but then do you give them hope? Do you give them respect? Love?

The truth is that you are fighting not some right-wing fundamentalist group as you imagine it but something much deeper and bigger that you do not even understand. It is called civilization. I don’t say we invented it because I don’t presume to think that way. It was what nature bestowed to us, and it taught us, at the very least, not to take slaughter and murder lightly.

We may not know yet how we will learn to see the truth again, but we are trying. Every day, we are living, and we are trying.